THE ESSENCE OF LEBANESE CUISINE

The backbone of Lebanese cooking is fresh, mostly plant-dominant ingredients, diverse mezze, extensive use of vegetables, grains, pulses, flatbreads, aromatic spices, and traditional sweets.

Lebanese breakfasts are often light, yet of a wide selection. Plain bread with jam or honey, manakeesh bread with za’atar, fatteh, a fried bread dish, foul medammes, a bean stew, white brine cheese akkawi, olives, fresh and pickled vegetables, and strained yogurt.

Lunch is a more substantial affair, the main meal of the day – a variety of mezze from vegetables and pulses, grilled or stewed meats, rice or bulgur pilaf, fresh salad accompanied by yogurt-based sauces, and a loaf of bread. Fruits may conclude the meal.

Dinner is lighter compared to lunch, especially on regular days or on no special occasions. During the celebration, the whole dinner can come in mezze platters or a traditional main course dinner, followed by appetizers.

GRAINS IN LEBANESE CUISINE

What feeds people every day is bread. Flatbreads are central in Lebanese cuisine and widely preferred over leavened loaves: khubz, manakeesh, and markouk – all staples in local households. They come with almost every meal and are used to scoop dishes, wrap around grilled items, and showcase hospitality. Thin, round breads vary by thickness and cooking method; many villages still bake flatbreads in communal ovens.

It is common for Levantine cuisines to use different types of grains in dishes: bulgur, semolina, freekeh. Cracked and partially pre-cooked bulgur may come in fine, medium, and coarse sizes and feature iconic Lebanese tabbouleh (salad), kibbeh (minced meat dish), and pilafs. Semolina, made from durum wheat, is used much like bulgur and also forms the base of coarse Lebanese couscous, giving it a pasta-like character. Freekeh is another form of young green wheat, roasted and cracked; it has a distinct smoky flavor. This ancient form of wheat is still widespread across Levantine cuisines.

Rice is commonly paired with meat, poultry, or lentils (mujadara, a dish of lentils, rice, and deeply caramelized onions), stuffed into vegetables and grape leaves, and served alongside stews. Rice pilafs with vermicelli are everyday staples. All other grains, although they may have had some importance historically, play a minor role today.

PRODUCE IN LEBANESE CUISINE

Lebanese cooking is full of protein-rich pulse dishes. Chickpeas feature in falafel, hummus, fatteh, and balila salad (chickpea salad). Fava beans appear in dishes like foul medammes and riz-bil-foul (broad beans cooked with rice and meat). Lentils are used in mujadara, adas bi hamod (lentils and silverbeet soup, simmered with potatoes in a tangy lemon broth), and other soups, often seasoned with cumin and served with a squeeze of lemon. White beans appear in fasolia stew.

Vegetables and vegetarian dishes are essential. Take, for instance, the iconic Levantine salad fattoush, with its crisp vegetables and toasted pita in a zesty sumac dressing. You’ll almost never see a mezze spread without tabbouleh, a refreshing parsley-dominant salad with bulgur and tomatoes. Lebanese cooks excel at stuffing vegetables with warak enab (stuffed grape leaves) and kousa mahshi (stuffed zucchini) dishes, both staples of the mezze spread and main courses. Eggplant is pickled in makdous, layered in moussaka, smoky and silky in rustic baba ghanouj dip, and rich and creamy in mutabal. Outside the region (Europe, US, elsewhere) most restaurants use baba ghanouj to mean mutabbal. What is the real difference between these two?

Mutabal is a creamy, smooth dip made from roasted eggplant mixed with tahini (sesame paste), garlic, lemon juice, salt, and often yogurt or labneh, giving it a rich, tangy, and nutty flavor with a velvety texture. It usually does not contain chopped vegetables and can be drizzled with olive oil and topped with sumac or parsley. Mutabal emphasizes a deeper flavor with tahini and garlic.

Baba ghanouj is a more rustic, salad-like dip with roasted, smoky eggplant, but it also includes chopped tomatoes, onions, mint or parsley, and sometimes walnuts or pomegranate molasses. It is vegan and emphasizes a smoky, earthy taste with a chunkier texture, often garnished with olive oil, paprika, or pomegranate.

No Lebanese table is complete without pickles. Everything from turnips to wild cucumbers can find a way into brine. Pickles add a tangy kick to wraps and accompany flatbreads or falafel. The pink color can be instantly spotted within mezze platters, as turnips are often paired with beets, which brings a bright pink color to the table.

Fruits are often consumed in their fresh form, towards the end of the meal. Other than that, smoothies and juices are prevalent. Dried figs, apricots, dates, and raisins are often paired with nuts for a snack.

MEAT IN LEBANESE CUISINE

Meat used to be pricey and was saved mostly for weekends and holidays. The traditional staples were lamb, goat, and beef. Pork was eaten too, but less so because of Islamic food rules and long-standing culinary traditions.

There’s a distinction between traditional meats and modern consumption patterns in Lebanon. These days, chicken is by far the most common on the table. If you look back about 70 years, lamb and goat were the main choices. But in the 1970s and 80s, as Lebanon’s economy grew and people had more spending power, diets started to shift. Poultry was cheaper and easier to get, so it quickly became a go-to source of protein and worked its way into everyday cooking. The same happened with beef. In many recipes that originally used lamb or mutton, beef has now taken its place.

Popular grilled dishes include skewers, shawarma, and kofte. Meat is also minced and stuffed into vegetables like zucchini, eggplant, or vine leaves, used as a topping for breads, or formed into kibbeh, a national dish of Lebanon.

Kibbeh is a fragrantly spiced ground meat mixed with bulgur, and it is made in a stunning variety of styles. These range from raw meat kibbeh neyyeah (traditionally, animals were slaughtered on Sundays, so the raw version was eaten immediately), to large pan-sized broiled kibbeh sahnieh, to football ball-shaped kibbeh mekliyeh, which is fried. All these recipes are handed down from grandparents to children as a part of cultural storytelling.

FISH AND SEAFOOD IN LEBANESE CUISINE

Though not as dominant as meat, fish and seafood have their place in Lebanese cooking, especially along the coast. In Beirut and the coastal towns, the tradition is to grill or fry the daily catch – fishes like red mullet, sea bream, or sardines – simply dressed with olive oil, lemon, and herbs. You’ll also see seafood mezze: fried calamari, shrimp sautéed in garlic and lemon, or octopus salads. A classic is sayadieh, a fragrant fish-and-rice dish cooked with caramelized onions and warm spices, finished with pine nuts, samke harra, a whole baked fish covered with a sauce of tahini, lemon juice, garlic, chili or hot pepper, and fish kibbeh.

MILK AND DAIRY IN LEBANESE CUISINE

Milk is rare in its raw form, but cultured milk products are trendy. Laban, a yogurt made from fermented milk from cows, sheep, goats, or a combination, is a staple, often accompanied by strained yogurt (sometimes called cheese) known as labneh. Ayran, a refreshing yogurt drink diluted with water, is also a popular beverage.

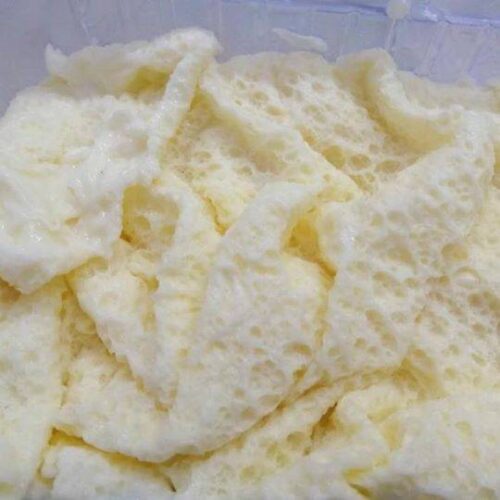

Kishk, jameed, or yogurt stone, is a traditional Eastern Mediterranean method for preserving milk. Milk or yogurt is mixed with bulgur, then naturally fermented and dried. It can later give a tangy kick when grated on salad, blended into soups, or used as a seasoning. Very common historically, especially in rural and pastoral communities. Even now, many families still make or buy it seasonally, and it remains a cultural marker in Levantine cuisine.

Cheese is also a part of dairy products. Most Lebanese cheeses feature sheep or goat milk, either exclusively or in combination with cow’s milk, and are brined, which means they’re soaked in salty water after the cheese is formed. Halloumi and akkawi are examples of local brined cheeses. Shanklish is another type of fermented cheese rolled in a mixture of spices, such as Aleppo pepper or thyme.

Eggs are used, but not a central ingredient in Lebanese cuisine. They appear in some everyday dishes, in pastries, and as a binding in kibbeh, still not as dominant as in European cuisines.

Clarified butter (samneh) and rendered lamb fat (awarma) were important animal fats for cooking and preservation, especially in mountain villages. Today, however, olive oil is the backbone fat in Lebanese kitchens, with vegetable oils also common.

NUTS AND DESSERTS IN LEBANESE CUISINE

In Lebanon, almonds, walnuts, and especially pine nuts are essential flavor builders and garnishes. You’ll find them toasted, scattered over rice-and-meat dishes, stirred into stews, folded into kibbeh, or layered into sweets like baklava and mafroukeh. Compared with much of the world, this heavy reliance on nuts is distinctive. In European cuisines, nuts are mostly tied to desserts; in East Asian cooking, peanuts and cashews show up in stir-fries, but not as a default garnish.

Lebanese desserts blend fragrance, texture, and tradition. One of the first things you notice is the aroma of rose water, orange blossom water, and sometimes mastic, a profile very different from the butter- or vanilla-heavy desserts of Western cuisines. Another feature is the balance between nuts, pastry, and syrup. Almonds, pistachios, and walnuts are layered between thin sheets of phyllo or folded into semolina-based sweets. Instead of heavy frostings or creams, the desserts are finished with a sugar syrup known as ater.

Texture is also important. A classic textural example is knafeh, with its crisp kataifi pastry on top, a stretchy cheese base underneath, and syrup poured over at the end. That contrast of crunchy, chewy, and soft is intentional, and you’ll find it repeated in many other desserts.

Lebanese sweets are also often made in small, shareable portions, good for pairing with coffee or tea. Many of these desserts are tied to religious and seasonal celebrations. Ma’amoul, for instance, is prepared around Easter and Eid, and during Ramadan, syrup-soaked pastries and semolina cakes take center stage.