THE ESSENCE OF TURKISH CUISINE

One may associate Turkish cooking with meat foods, such as the worldwide known kebabs, which are a great specialty of this country. However, the backbone of the local diet is slightly different from the first impression – the vegetables, grains, and fruits – all plant-based foods on plates every day. Fish, seafood, and meat account for only 5% of the ration and are often indulged during festive occasions rather than daily. Yogurt, on the other hand, is essential to nearly every meal. If yogurt is not on the plate, it is probably in a glass next to a meal – in the form of ayran, a national fermented milk drink.

Unlike in Southern Europe, Turkish breakfast is a real social custom of family gathering that sometimes goes beyond a dinner. Fresh bread is at the center, followed by cheeses, olives, eggs, jams, sometimes sausages, and dried cured beef pastirma.

Lunch is often the main cooked meal of the day, consisting of a starter such as a lentil or yogurt-based soup, followed by bean dishes with bulgur or rice pilaf, fresh bread, stews, and salad. It is common to prepare a few staple dishes in bulk to be on hand at home for family meals.

In the afternoon, it’s usual to have a small snack, with tea or coffee, which, interestingly, both are integral to Turkish culture. This black sweet tea is served in small tulip-shaped glasses, consumed throughout the day, and is a part of Turkish hospitality. Turkish coffee is strong, finely ground, and brewed with water and sugar in a special pot called a cezve.

Dinner is also an extensive meal in Turkey; it consists of meze – small appetizer dishes meant for sharing, grilled vegetables or meat, casseroles, pilafs, yogurt dishes, and bread. Meals often end with sweet desserts.

GRAINS IN TURKISH CUISINE

Wheat dominates Turkish grain consumption, especially in the western regions where temperate climate and fertile soil favor its cultivation. This Western preference for wheat also reflects centuries of contact with Mediterranean and European wheat-based cuisines.

For thousands of years of traditions, bread has been the most repetitive component of every meal – eaten even if not particularly suited for the meal. Turkish people eat the most bread in the world, 199.6 kilo per person per year (source). Somun ekmek — fluffy and golden loaf bread, bazlama ekmek — leavened circular bread, yufka ekmek — phyllo bread, pide — pita bread with rich toppings, lavas — flatbread, thicker than yufka, but thinner than pide, misir ekmegi —cornbread, simit — circular bread encrusted with sesame seeds, quintessential street food, are prevailing types of bread.

Chewy, nutty bulgur is the most-eaten wheat product in Turkey’s mainland, commonly used to make pilaf, added to soups, or mixed with meat for dolma—stuffed and sarma—filled veggies.

Due to heavy rains, the eastern part of Turkey near the Black Sea is not well-suited for wheat. This led to corn and cornflower meals, known as mısır in Turkish. While corn is not native to Turkey and wasn’t part of traditional cuisine, it has been integrated into bread, pilafs (mısır pilavı), soups (mısır çorbası), and puddings (mısır helvası).

Rice is a primary companion in stuffed meat and vegetable dishes. Still, most frequently, it is served in the form of pilaf, for which people have very high standards. While making a Turkish pilaf, use medium to long grain rice, sauté in butter or oil with onion and garlic, spice with cumin, cinnamon, and allspice, and then cook with broth. Pilafs often come plain as a side but can also be enriched with chickpeas, nuts, dried fruits, and sometimes meat for a standalone dish.

PRODUCE IN TURKISH CUISINE

Turkey is a place for a vegetarian to thrive. Countless vegetable dishes and side preparations, all made from locally grown greens. Fresh, fried, roasted, stuffed, and served with garlic-infused yogurt, vegetables are the essence of Turkish cuisine. Veggie consumption is second highest within Mediterranean countries (after Tunisia).

Turkish specialty is stuffed vegetables: dolma or sarma. Both stuffed with a mix of rice, minced meat, herbs, and spices. Dolma is more generic and refers to any stuffed vegetable – bell pepper, zucchini, eggplant, or tomatoes. Sarma, specifically, is a roll of grapevine leaves. All sarma can be considered dolma, but not all dolma are sarma.

Artichokes, broad beans, and eggplants are extremely popular. Salads vary from the simplistic watercress in yogurt to a salad of garlic-infused smoked eggplant. Grilled sivri biber – long, green pepper of mild heat will likely add a smoky flavor to kebabs and grilled meats. It is common to meet grilled sivri biber and sumac-flavored onions on the same kebab plate.

Tursu – pickled vegetables in garlicky brine is a traditional appetizer. In some families, no meal is considered complete without a bowl of tursu on the table (source).

Potatoes are indeed used in Turkish cuisine, but they are not as central as bread, rice, and bulgur. Turkish cuisine loves stuffed vegetables, so it comes as no surprise that the famous potato dish also comes stuffed – kumpir, baked potatoes with toppings. While in Western countries, it is expected to have boiled, fried, or baked potatoes as a side dish, it is not as common here. Turkish cooks creatively incorporate potatoes in a salad (with olive oil and lemon or vinegar-based dressing and includes pickles, red peppers, and parsley), mashed and in combination with eggplant in dishes like hünkar beğendi (eggplant puree with mashed potatoes) or musakka (sliced potatoes, layered with eggplant, ground meat, and a tomato-based sauce).

Fruits are local, plentiful, and cheap, eaten after meals to refresh the palate (cubes of watermelon, for instance) and as a dessert. What differs in fruit consumption from Western cuisines is that Turkish cuisine generously incorporates dried apricots, figs, grapes, dates, mulberries into everyday diet. During weddings, engagements, or religious celebrations, offering guests various dried fruits is a must. Also, during the holy month of Ramadan, when Muslims fast from sunrise to sunset, dates, a natural nutritious sweet, are often consumed to break the fast. Dried fruits feature savory dishes, like ayva dolması – stuffed quince, çağla aşi – a fresh almond dish with lamb, fruit, yogurt, garlic, yeni dünya kebab – lamb stuffed loquat fruit.

As a Mediterranean country, Turkey produces lots of grapes, and they are either eaten fresh, dried to raisins or made into Turkish special grape molasses, called pekmez. Before sugar became widely available, honey and pekmez were used to sweeten the traditional Turkish ration.

MEATS IN TURKISH CUISINE

Common meats in Turkey are beef, mutton, lamb, goat, and chicken; pork is omitted. Minces are popular, as this form can absorb many flavors, provide a singular texture for grilling, and allow more economical cuts to become tender. Chicken has recently become the most popular meat due to its versatility and affordability, though beef, lamb, and goat have always been preferred as specialties.

Kebabs are quintessential, especially when there is an open flame to grill the meat, and if there is none, Turkish people will find a way to get it done. Over time, different regions within Turkey developed their unique styles of kebabs. Kebabs refer to a food group of well-seasoned, marinated, grilled, or roasted meat served on skewers with vegetables and bread. Traditionally, kebabs would have been done with lamb, but with evolving tastes and regionalities, meats have extended to beef, chicken, offals, fish, and vegetables. The serving may also differ – on a plate, in a sandwich, or in lavash. There are close to a hundred varieties of kebabs, for the most widespread in Turkey, visit our iconic dishes section.

Other than kebabs, koftes are also popular; it refers to seasoned patties or meatballs from minced or ground meat, mixed with onions, garlic, and herbs; shaped into balls, patties, or elongated forms and can be cooked in different ways, including grilling, frying, or baking.

Offals have a special place in Turkish cuisine as they are cheaper than other animal parts and also very nutritious. Most offal dishes have thyme, chili, and garlic flavoring and are served with bread as a rich and hearty meal. Offal dishes in Turkey include brain salad, fried brains, grilled spleen, liver, kidney, sheep intestines, tripe soup, trotter soup, etc. – there are even restaurants that specialize in serving these dishes!

FISH AND SEAFOOD IN TURKISH CUISINE

As a country surrounded by four seas and abundant with creeks, rivers, and lakes, Turkey has plentiful access to fish and seafood, yet domestic consumption is low. Turkey is a big nation with a lot of population living far from coastlines, focusing on terrestrial staples.

The coastline areas, though, do have their beloved underwater ingredients: the Black Sea areas are famous for their anchovies, which are a beloved fried; horse mackerel is caught from the Marmara Sea; sardines of the Dardanelles and sea bream from the Aegean Sea are preferred fishes. Fish preparations will most frequently be grilled fish balık, seafood mezes, and stuffed mussels midye dolma. Balık ekmek, a grilled fish sandwich, is a popular street food along the coasts.

EGGS AND DAIRY IN TURKISH CUISINE

Though it is difficult to trace the exact roots of the origin of yogurt and attribute it to a particular ethnic group, Turkey and the West Asia are the areas pinpointed most frequently. Turkish yogurt dates back 4000 years; it was likely first made by nomads who herded sheep and goats and found a way to preserve dairy products longer in air temperature. Also, yogurt was easier to digest than milk because of bacteria breaking down the lactose in milk (yogurt was the first probiotic). Once found, yogurt quickly spread throughout the West Asia, becoming and remaining a staple.

Today, yogurt is a fundamental ingredient in Turkish cooking; it even goes beyond food with a local proverb.

Meaning that if you’ve had a bad experience with one thing, you’ll be cautious when reencountering something similar (source). Turkish yogurt is rich, creamy, usually plain, strained yogurt (straining is a process when whey is removed from yogurt, resulting in a creamy and dense texture). Strained Turkish yogurt and strained Greek yogurt are pretty similar, both are known for thick and creamy textures. However, the straining duration and methods may vary, leading to slight differences in texture. Some people claim that Turkish yogurt has a milder taste compared to its Greek counterpart. The taste may vary based on the specific bacterial cultures used and the source of the milk.

Cheese in Turkish daily practice is not as popular as in Greek, Italian, or Spanish cuisines. Distinctively from Western tradition, Turks like to add herbs and other flavorings to the cheese. Some local Turkish cheeses include beyaz peynir, white brined, crumbly cheese, kaşar, semi-hard, similar to cheddar, used in borek, pide, tulum cheese, a unique variety aged in animal skin, giving it a distinctive flavor, otlu peynir, herbed cheese.

Lots of vegetable oils are used in Turkish cooking. Olive oil is a major component of many dishes in the western part of the country, where olive trees grow. There is actually a whole group of foods in Turkish cuisine named zeytinyağlılar, which translates to olive oil dishes.

DESSERTS IN TURKISH CUISINE

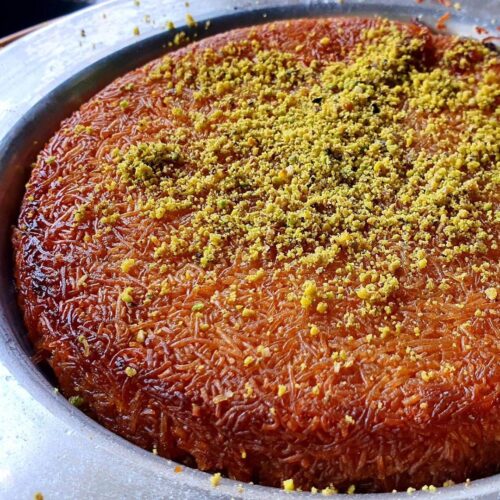

Turkish desserts are characterized by their richness and complexity of textures. In contrast to many Western desserts that focus on butter and subtle sweetness, Turkish desserts are unapologetically sweet, often made with syrups, honey, or fruit molasses. sprinkled or stuffed with pistachios, walnuts, and hazelnuts.

A chewy, sweet, gel-like candy is one of the most widely known “Turkish delights” outside of Turkey, it is a local lokum made from sugar, starch, water, and various flavorings.

A defining feature is the layering of textures. From the crisp phyllo dough of baklava to the delicate, chewy strands of kadayıf – spun pastry, Turkish sweets often play on the contrast between crunchy exteriors and soft fillings. Cheese, especially in desserts like künefe, adds a savory layer and a unique salty-sweet experience. Spices and aromatics – rosewater, orange blossom, mastic – give Turkish desserts a floral and fragrant dimension rarely seen in European desserts.