THE ESSENCE OF THAI CUISINE

At its core, Thai cuisine consists of lightly prepared yet boldly flavored dishes, highlighted by herbs and aromatics. Thai meals are built on jasmine rice, noodles, fish, seafood, and then various fermented fish products, chilies, lime, coconut milk, palm sugar, lemongrass, galangal, Thai basil, and many more characteristic spices layer the complexity of flavors.

Traditional Thai meals carefully blend the intense heat of bird’s eye chilies with the sour brightness of lime, tamarind, or vinegar, the sweetness of palm sugar and coconut milk, and the saltiness derived from fish sauce or soy sauce. This play is deliberate, every element balances another – spicy dishes offset by cooling cucumber or mild rice, sourness is harmonized with sweetness, and aromatic herbs elevate the whole experience.

Thai meals consist of rice with many complementary shared dishes served at once, including soups. It is also customary to provide more dishes than there are guests at a table. A selection of dishes forms a harmonious contrast of flavors, textures, and preparation methods. Traditionally, a meal should have at least five elements: a dip or relish for vegetables (khrueang chim); a clear soup, a curry or stew; a deep-fried dish; and a stir-fried dish.

Ultimately, Thai cuisine is not only about flavor, but about creating a shared, sensory experience that nourishes both body and social bonds.

THE AUTHENTIC THAI CUISINE

Authentic Thai dishes differ from those served abroad. In local street stalls, you may expect way more intensity – lots of fish sauce, chillies, galangal. Abroad, the same dish can be more adapted locally – milder spice, more meat or other protein per dish, sometimes disproportionately high compared to authentic portions. Tourist-focused restaurants even within Thailand serve versions that are more “Western-friendly,” with creamier curries, but lacking the spicy or sour punch. Authentic dishes would more often have chicken with skin, fried whole fish with head and tail, and stinky pungent aromas from fermented fish. Many Thai dishes are now familiar in the West, but the vast majority are not. In many of them, different kinds of protein, or combinations of protein, are interchangeable as the main ingredient; it’s either beef, chicken, duck, tofu, prawn, carb, shellfish, or eggs.

GRAINS IN THAI CUISINE

Rice is foundational to almost every meal. It is so integral that the Thai word for rice khao also means ‘food’.

Once the rice is steamed or cooked, it is called khao suai, ‘beautiful rice’. Rice is a base to soak up sauces, balance and tone down spiciness, and harmonize contrasting flavors on the plate. Jasmine rice is the most common, as they are aromatic, slightly nutty, fluffy, and gets a slightly sticky texture after cooking. Sticky or glutinous rice is popular in Northern Thailand and eaten with hands; it’s used in savory meals and desserts like mango sticky rice. Other varieties include red rice and brown jasmine rice.

Rice is dominant, but noodles are hugely popular! Made from the flour of rice, wheat, or mung beans. One of the oldest types of noodles in Thailand is khanom chin, fresh rice vermicelli made from fermented rice, eaten with green curry (kaeng khiao wan), with chicken or in green papaya salad (som tam). Chinese migrants subsequently introduced other noodle varieties. The three most common now are sen yai, wide flat; sen lek, narrow flat; and sen mi, round and thin rice vermicelli. A fourth popular variety, bami is made from egg and wheat flour and is usually sold fresh. A fifth type, wun sen or glass noodles, are thin, round noodles made from mung bean and sold dried.

Pad Thai is Thailand’s most famous noodle street food around the world. It uses thin, flat rice noodles, stir-fried with a sweet and savory sauce made from tamarind, fish sauce, palm sugar, and lime. Crushed peanuts, bean sprouts, tofu, and shrimp or chicken complete the dish. Pad see ew is another street food staple that is all about that umami from soy sauce. Drunken noodles, pad kee mao, are spicy and supposedly perfect for a hangover. These use wide rice noodles as well and are stir-fried with lots of fresh basil, chilies, garlic, meat, or seafood.

In many parts of Southeast Asia, rice noodles are fermented instead of dried. In hot, humid regions, dried noodles were harder to keep dry without mold before modern packaging. Freshly made, lightly fermented noodles could be produced daily and eaten within hours, fitting local market culture. Fermentation changes the starch structure, giving noodles a soft, springy bite and a slight tang – all valued in these cuisines, whereas dried noodles lose that subtle sourness and become firmer. Also, rice noodles spoil faster than wheat noodles when fresh, so fermentation helped preserve them just long enough for distribution and sale. An example dish is kanom jeen – thin, slightly fermented noodles of a mild sour note, served with various curries, soups, or chili-based sauces.

Starting from the 1970s, wheat began gaining popularity in Thailand, driven by the emergence of instant noodles – precooked, dried noodle blocks made from wheat flour and designed to be cooked quickly. The drying process is done by frying the noodles in oil, creating a porous structure that allows for rapid rehydration and cooking, which makes them convenient but low in nutritional value. This rise of instant noodles marked a significant shift in Thai dietary patterns, moving away from the traditional rice and vegetable-based meals.

PRODUCE IN THAI CUISINE

Typical veggies of Thai cuisine are various eggplants, like the pea-sized makhuea phuang and the egg-sized makhuea suai, often eaten raw. Although broccoli is often used in Asian restaurants in the West, it is rarely seen in Thailand. Here, khana is used, for which broccoli is a substitute. Long beans, bean sprouts, bamboo shoots, cucumbers, Chinese kale, choy sum, sweet potatoes, several types of squash, and winged beans are often-used vegetables. Leafy vegetables and herbs are eaten raw in a meal or as a side dish.

Several types of mushrooms feature in Thai cuisine, such as straw mushrooms, shiitake, and white jelly fungus. Flowers are also common, either as a vegetable or as a coloring.

Tofu is not a staple food in Thailand the way rice is, but it became widely used after being introduced by Chinese immigrants. It can be firm, soft, or fried; it is commonly added to pad thai; it is sold as fried snacks by street vendors; and it is used in vegan versions of traditional recipes.

Unripe and sour fruits are especially popular in Thailand compared to most other cuisines. The crisp, tart texture is valued rather than avoided. Fresh fruits are served after a meal as dessert with spicy dips made from sugar, salt, and chilies. Fruits feature salad – especially the well-known green papaya salad som tam, also pomelo salad yam som-o, also soups with tamarind juice such as tom khlong and kaeng som. In Thailand, one can find papaya, jackfruit, mango, mangosteen, langsat, longan, pomelo, pineapple, rose apples, durian, Burmese grapes, and other native fruits. Apples, pears, peaches, grapes, and strawberries, which do not traditionally grow in Thailand and in the past had to be imported, have become increasingly popular in the last few decades.

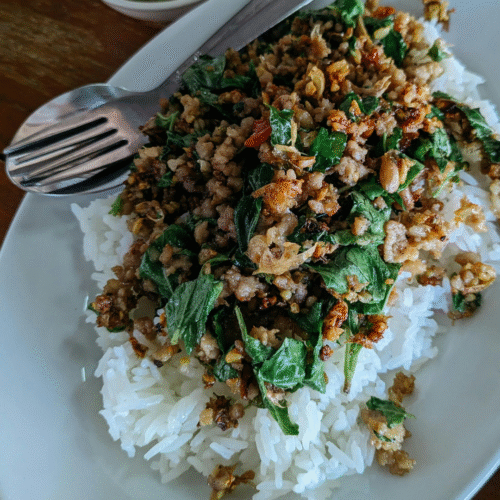

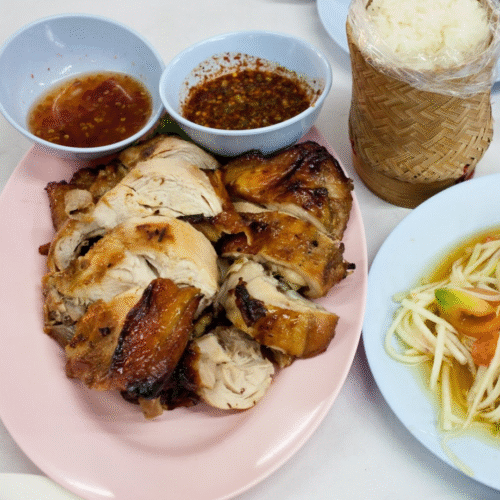

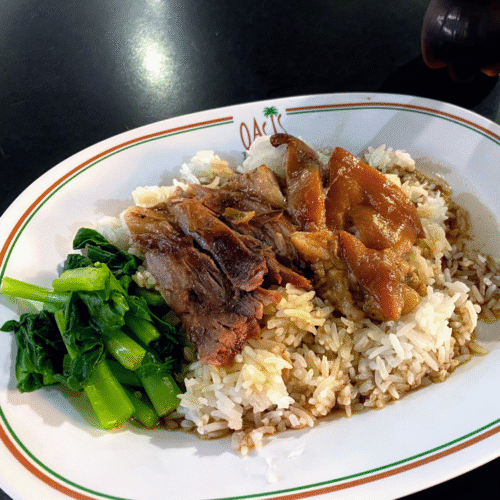

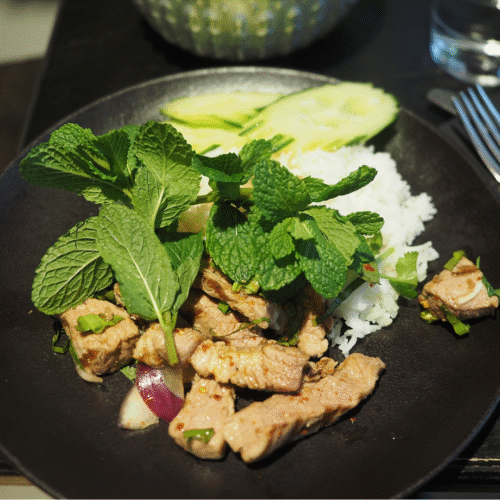

MEAT IN THAI CUISINE

Meat is moderate in Thai cuisine. Pork leads the popularity, followed by chicken, duck, beef, and water buffalo. Goat, lamb, and mutton are rare, except among Muslim Thais in the Southern part. A famous dish is khao kha moo, which is slow-braised pork leg stew served with rice, marinated vegetables, and a soft-boiled egg. Chinese BBQ pork (char siu) is also popular. Gai yang, grilled chicken marinated in garlic, soy sauce, coriander, and spices, is a classic and very popular throughout Thailand, served with sticky rice and a spicy sauce. Hat yai fried Chicken is another beloved chicken dish. Other favorites include larb, minced pork or chicken salad with herbs and spices, satay, marinated pork or chicken skewers served with peanut sauce, and crispy deep-fried pork or chicken Moo/Gai Grob.

Thai diet is traditionally fish and rice-based; meat complements dishes, not dominates. Recent surveys indicate that although about three-quarters of Thais eat meat, a significant portion (around two-thirds) express interest in reducing their meat consumption, favoring alternative plant-based proteins instead. The market for alternative meat products is also growing in Thailand.

FISH AND SEAFOOD IN THAI CUISINE

Pescatarians could thrive with Thai food – hundreds of dishes contain fish and seafood from rivers, lakes, ponds, paddy and tropical seas. Mackerel, Asian sea bass, Nile tilapia, catfish, and fishballs are enjoyed throughout the country. The diversity of seafood is also remarkable. Shellfish, crustaceans served fried, raw, fermented. Every part of the seafood is valued, from the heads and roe to the tender flesh, often cooked with coconut milk, steamed, or fried with noodles.

Tourist menus often highlight well-known tom yum goong or pad thai, but many authentic dishes remain overlooked. Search for hor mok steamed fish custard, pla neung manao steamed sea bass with lime sauce, yen ta fo pink noodle soup with seafood, pooh paht pong karee Thai crab curry, hoy kraeng blood cockles. Why overlooked? Some dishes may have a sour and spicy flavor that can be an acquired taste. Others require more effort to find, such as hor mok or boat noodles with thickened broth.

Southeast Asian cuisines, Thailand includes extensive use of fermented fish and seafood as flavorings (see more in ‘key flavorings’ section) to create salty and deep umami.

INSECTS IN THAI CUISINE

Thailand hosts more than 200 edible insect species – second only to Mexico – and the practice of insect-eating remains in rural North and Northeast regions, where insects are a free, accessible meat substitute. Local markets overflow with live and fried beetles, crickets, ants, caterpillars, cicadas, giant water bugs, red ant eggs, and buttery bamboo caterpillars. Giant water bugs, for instance, are noted for their strong aroma reminiscent of blue cheese; red ant eggs feature ‘Gaeng Kai Mot Daeng’ curry. Thailand’s insect industry has grown robustly, attracting both local markets and export demand.

Despite this, the challenge of overcoming the ‘gross factor’ remains. This got producers to innovate and process insects into flours and powders that can be incorporated into bread, cocoa, and noodles.

EGGS AND DAIRY IN THAI CUISINE

Traditional Thai cuisine is mostly dairy-free, lactose intolerance is quite common among Thais (around 47% to 80%). Dairy consumption started to develop only in the 1960s. Today, milk, butter, yogurt, and specialty cheeses are available mostly in urban areas. Traditional Thai food largely uses coconut milk as a primary creamy ingredient instead of dairy milk.

Eggs are often a supporting protein, kept on street stalls to bulk up the dish. In stir-fries, eggs add softness and bind ingredients; in fried dishes, they provide a coating stick. Salted duck eggs (kai khem) are a staple, appreciated for their salty flavor and oily yolk, eaten with rice soups, rice porridges, and salads. Century eggs (kai yiew ma, from Chinese influence) bring rich, savory, sometimes sulfurous notes. Eggs are essential in Thai custards (sangkhaya) and golden egg-yolk sweets (thong yip, thong yod, foi thong).

NUTS AND SWEETENERS IN THAI CUISINE

Coconut milk is an absolute staple (coconuts are reported under ‘oilcrops’ in FAO data). Its extensive use was likely influenced by South Indian coconut milk curry traditions, adapted over time and now inseparable. Thais not only consume the nut (actually a drupe), but also make use of the growth bud of the palm tree as a vegetable. From the stalk of the flowers comes a sap that can be used to make coconut vinegar, alcoholic beverages, and sugar. Coconuts are most consumed in the southern part, coconut palms do not grow as well in northern and northeastern Thailand.

In the global context, Thai desserts feature tropical fruits, coconut milk and cream, palm sugar, rice flour, and glutinous rice. These ingredients create uniquely rich, creamy, and subtly sweet bases. Aromatic elements are essential, often using jasmine, pandan leaves, and other fragrant plants. Dessert textures revolve around stickiness – sticky rice, soft custards, layered jellies. Traditional sweets use natural colorings from pandan (green), butterfly pea flower (blue), saffron or egg yolks (yellow/gold), and roselle (red). Many Thai desserts carry auspicious meanings. Unlike some Western desserts that may be intensely sweet, Thai desserts balance sweetness with aromatics, hints of saltiness and richness from coconut.