THE ESSENCE OF MEXICAN CUISINE

Mexican cuisine is built on a foundation of corn, beans, and chili peppers – ingredients that have sustained the region for thousands of years. It’s about layering flavors through roasting, grinding, and slow-cooking simple ingredients and balancing heat, acidity, and earthiness. Chilies provide not just spice but nuanced smoky, sweet, bright, or fruity flavors. Lime juice, tomatoes, and tomatillos add brightness that cuts through rich elements. Corn and beans appear everywhere. Though nowadays Mexican cuisine widely incorporates rice, pork, and cheese, once brought by Spanish colonizers, in essence, it’s always been about making the most of what’s available locally.

MEXICAN MEAL STRUCTURE

Daily meal structure is quite different from the usual three-meals-a-day pattern. The day begins with a light breakfast, desayuno – coffee with milk café con leche, sweet bread pan dulce, and fruit. By mid-morning, around 10-11 AM, comes almuerzo, a more substantial second breakfast outside of home – usually at food stands, offering tortilla chilaquiles, eggs huevos rancheros, refried beans, enchiladas, tamales, sopes, fresh juice. La Comida is an elaborate multi-course meal of pozole soup, meat tacos de carnitas; stuffed poblano peppers chiles rellenos, and grilled meats carne asada. Many businesses close for comida. In the late afternoon, around 6-7 PM, some people enjoy merienda, a light snack similar to European tea time. The day concludes with cena, consisting of simple late-night snacks, antojitos like tacos, quesadillas, and tamales.

Among the most popular drinks is atole, a warm, thick beverage from corn masa, sometimes transformed into champurrado when chocolate is added. Pulque, one of Mexico’s oldest alcoholic drinks, is a milky-white, fermented agave sap drink that was considered sacred by the Aztecs. It predates both mezcal and tequila. Chocolate-based drinks, aguas frescas made from hibiscus, horchata (a rice-based drink), and tamarind are popular.

GRAINS IN MEXICAN CUISINE

The Mayans believed humans were literally made from corn by the gods; they called themselves ‘people of corn.’ In the previous chapter, we already mentioned the nixtamalization process, after which the corn is transformed into masa, the foundation of numerous Mexican dishes:

• tortillas, both eating utensils and wrapping;

• tamales, steamed in corn husks or banana leaves;

• tlacoyos, similar to thick tortillas, stuffed with beans or cheese;

• gorditas, split corn cakes filled with various ingredients.

Even drinks feature corn, like atole, a warm, thick beverage made from masa, and tejuino, a fermented corn drink popular in certain regions.

In traditional Mexican homes, the rhythmic clapping sound of hands making tortillas is just part of everyday life.

Wheat arrived with Spanish colonizers in the 16th century and adapted well to northern Mexico’s climate. Today, states like Sonora are major wheat producers, and you’ll notice wheat becomes more prominent in Mexican cooking as you head north. Wheat features tortillas, empanadas, sauces, pasta, and breads. Think of pan dulce sweet bread, found in every panadería, bolillos, crusty rolls perfect for tortas, and sweet conchas with their distinctive shell-like tops.

Rice, also introduced by the Spanish, became a staple side paired with beans. The classic preparation is arroz rojo (red rice) or arroz mexicano, where fluffy grains are cooked with tomatoes, onions, and garlic.

Other ancient grains like chia and quinoa aren’t as common, but they’ve got deep roots in Mexican cooking. Chia seeds used to fuel Aztec warriors back in the day, and you’ll still find them in drinks like agua fresca de chía.

VEGETABLES IN MEXICAN CUISINE

In Mexico, vegetables aren’t little sad sides on a plate alongside meat and grains; they’re chopped, diced, sliced, and pureed into beautiful sauces and garnishes that define the dish’s character.

Avocados are the green gold of Mexico – creamy, nutty flesh pairs well with spicy tacos and sandwiches; avocados feature soups, salads, and the already famous guacamole. Guacamole has been made since Aztec times, though the original version was mashed avocados. The word ‘avocado’ comes from the Nahuatl word ahuacatl, which means ‘testicle,’ named for its shape and believed to have aphrodisiac properties.

Little foods come without chiles in Mexico – the country has about 64 different species, with hundreds of varieties. Some of the most well-known varieties are fresh – jalapeño, poblano, chilaca, mirasol, serrano, habanero, chile de árbol and some dried – chipotle (dried and smoked jalapeño), ancho (dried poblano), mulato (a darker dried poblano), pasilla (dried chilaca), guajillo (dried mirasol). Dried chiles are integral to sauces such as mole, as well as in salsas and marinades.

Traditional salsas often combine tomatoes, onions, cilantro, and chiles such as jalapeño or serrano, blended to the desired consistency. The habanero chile is among the spiciest (100,000-350,000+ SHU on the Scoville scale), usually used in Yucatán cuisine. After having a bite, jalapeño may feel like a warm sun on your tongue.

Beyond their flavor, chiles were always valued locally for their preservative properties in a warm climate, helping to prevent food spoilage. Eating spicy food causes the body to produce endorphins, creating a pleasant sensation that reinforces their continuous use.

The common misconception is that all Mexican food is spicy. While chiles are staples in most dishes, they’re equally used for their distinct flavors, aromas, and colors as much as for their heat. Often, chiles are roasted, seeded, or soaked to reduce heat, paired with yogurt and citrus. In contemporary Mexican dining, it’s entirely possible to enjoy a full Mexican meal without spiciness. On the other hand, toddlers in Mexico start eating mild chile peppers with salsas at a young age; this gradual introduction is seen as a form of cultural integration.

Other staple vegetables of Mexico include beans, squash, tomatoes, tomatillos, Mexican husk tomatoes, nopales (cactus pads), chayote (a green, pear-shaped vegetable with a crisp texture and a mild, slightly sweet, and nutty flavor), and jicama, a Mexican turnip. Tomatillos are grown similarly to tomatoes and are key in salsas and sauces for their tanginess. Chayote is used in salads, soups, and stews. Nopales is a rather unusual ingredient, usually cleaned of spines, sliced, and can be grilled, boiled, or sautéed for use in salads, tacos, and stews. Jicama is a crunchy, slightly sweet root vegetable, often eaten raw in salads or as a snack, seasoned with lime and chili powder.

Many tropical fruits are grown in Mexico – limes, mangoes, papayas, platanos, guavas, soursop (anona), prickly pears, mameys (sweet and creamy oval shaped fruit described as a mix of sweet potato, pumpkin, and apricot), blackberries, black sapotes, pitayas, passion fruits, star fruits. Also, many regional, exotic, limited, and intensely flavored fruits. On the street stalls, it’s common to add chile and lime to fresh fruit or prepare mixed fruit cups with a sprinkle of tajín spice on top.

Fresh lime is a symbol of Mexican cuisine, a key ingredient, and an essential table staple. It is totally not indigenous here. It arrived from Southeast Asia in the 16th century and filled a crucial gap in pre-Hispanic cuisine by balancing chile heat, adding brightness to salsas, and preserving ingredients. Quickly, it became irreplaceable.

One of the most misunderstood Mexican fruits is the black sapote, or the ‘chocolate pudding fruit.’ Despite its nickname, it contains no chocolate at all – just a dark flesh with a consistency and flavor similar to chocolate pudding when fully ripe.

Mamey sapote is a unique fruit – its salmon-colored flesh tastes like a combination of sweet potato, pumpkin, and almond, with notes of vanilla and berry. The fruit appears in traditional milkshakes (mamey smoothies are popular in Mexico City), ice creams, and savory dishes.

MEAT IN MEXICAN CUISINE

In Mexican cooking, meat serves as a flavoring rather than the main focus of a dish, like in pozole, where small pieces of pork enhance the hominy-based soup, or in tamales, where meat filling complements rather than dominates corn masa. Even tacos, which Americans think of as meat vehicles, are really about the balance between protein, salsa, and all those other flavors dancing together.

In northern Mexico, due to its ranching tradition, beef is more prominent, think carne asada (grilled meat) and machaca (dried spiced beef of pork). Coastal regions rely more on seafood; in central and southern Mexico, pork and chicken are common.

Mexican cooks are masters at taking cheaper cuts and elevating them. Barbacoa is probably the best example – this ancient technique of slow-cooking in underground pits lined with agave leaves. Modern barbacoa might not always involve digging holes in your backyard, but that same philosophy of patience and technique lives on. Take cochinita pibil – pork marinated in achiote and sour orange, wrapped in banana leaves, and cooked until it’s basically meat butter. Or birria, where tough goat or beef gets transformed through hours of slow cooking with chiles and spices.

FISH AND SEAFOOD IN MEXICAN CUISINE

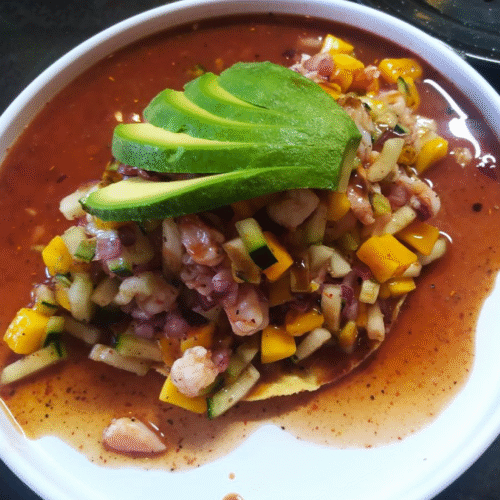

One of the most iconic Mexican seafood dishes is ceviche, a raw fish dish, where the fish is ‘cooked’ by the acidity of lime or lemon. Ceviche has origins in both Mexican and Peruvian cuisine, but its exact origins are still debated. When the Spanish arrived in the Americas and encountered these raw fish preparations, they incorporated them into their menus. As the Spanish colonized various parts of Latin America, ceviche spread and evolved. Mexican ceviche typically features snapper or halibut, chili peppers, onions, tomatoes, and avocado, which distinguishes it from the more minimalist Peruvian style. Mexican ceviche often marinates for 3-4 hours to allow the lime juice to thoroughly infuse with the ingredients. The result is a bright, refreshing, and very tangy dish.

Baja-style fish tacos are another beloved specialty. Originating in the Baja California region, these tacos feature lightly battered and fried white fish, cod, or halibut, served in small corn tortillas and topped with shredded cabbage, pico de gallo, and a creamy sauce.

Other popular Mexican seafood dishes include grilled or sautéed shrimp, octopus in various preparations, and whole-roasted or fried fish, such as huachinango (red snapper) or huachinango a la Veracruzana, where the fish is baked with a tomato, olive, and caper sauce.

EGGS AND DAIRY IN MEXICAN CUISINE

Mexicans do seem to like their eggs. An average per capita egg consumption of 345 eggs per year – almost every Mexican eats an egg a day, or over 21 kilos of eggs consumed yearly! Within the 50 years since the industrialization of poultry farming began, egg consumption in Mexico has grown around six times. Eggs are a convenient protein source and economically more accessible than meat. Purposeful marketing campaigns promoted eggs as highly nutritious, and they are well-fitted into the majority of Mexican dishes.

Milk and dairy are not as ubiquitous as in some other cuisines. Cheese, such as queso fresco, is more used than milk or cream in traditional cooking. Additionally, cotija cheese, an aged, salty, and crumbly cow’s milk cheese, pairs well with tacos, enchiladas, and tostadas. Dairy-based dishes and beverages, such as horchata and flan, are more common in certain regions or as part of specific celebratory meals rather than widespread staples.

SUGAR, FATS, AND NUTS IN MEXICAN CUISINE

Dessert culture in Mexico emerged after the Spanish introduced sugar and expanded the range of desserts. Pre-Hispanic cultures enjoyed chocolate, but it was consumed as a warm, syrupy drink mixed with honey. The arrival of European milk, dairy products, cinnamon, and native vanilla, pecans, peanuts, fresh and dried fruits, and piloncillo (unrefined cane sugar) are common ingredients of Mexican desserts. Sweet bread (pan dulce) of various flavors and shapes is popular, along with milk-based desserts like dulce de leche, fried desserts such as churros and buñuelos, and fruit-based candies and preserves.

Mexican desserts are often less intensely sweet than American or European ones. Many sweet items are eaten as snacks (merienda) throughout the day rather than after meals.