THE ESSENCE OF INDONESIAN CUISINE

Indonesian cuisine is not homogeneous but rather an eclectic mix shaped by varied ecosystems. What regions have in common is a reliance on starches, fermented products, and spicy condiments. Rice anchors almost every meal; everything else is just the supplements. Cassava, sweet potatoes, and sago are important secondary staples. With the world’s second-longest coastline, fish is even more prevalent than meat, which is consumed moderately and saved for occasions. Fiery sambal chili paste and sweet soy sauce kecap manis will follow virtually every meal (of the eastern islands), as well as krupuk, deep-fried crackers of various flavors, which are a common side.

Mealtimes are not strictly set – they’re observed differently across regions. In western and central Indonesia, the main meal is cooked in the late morning and consumed around midday. Most of the dishes are made so that they can remain edible even if left on the table at room temperature and reheated for the evening. A typical meal would consist of steamed rice, surrounded by vegetable dishes, soup, and meat or fish side dishes. During a typical meal, each dish is placed in a large communal plate; the oldest family member or the husband has the right to initiate it. Indonesians eat with a spoon in the right hand and a fork in the left. Knives are absent from the dining table as most vegetables and meat are already bite-sized.

WHY INDONESIAN, MALAYSIAN, AND SINGAPOREAN DISHES ARE OFTEN CONFUSED

Indonesian, Malaysian, and Singaporean cuisines are often confused overseas due to their geographical proximity and overlapping rice, coconut milk, fermented products, seafood, chili, and spices; also, steaming, frying, and curry-making are staples in all three countries. Satay, rendang, nasi lemak, and laksa have versions in all three countries, leading to frequent cross-identification. Indonesian cuisine is distinct for its extensive regional diversity, with thousands of islands, and has a broader variety of flavors. Indonesians commonly use palm sugar, kecap manis, indigenous galangal, and candlenut, which give food a characteristic sweet and savory profile. Unique to Indonesia is the distinct use of sambal varieties, more assertive flavors, and the rare use of wheat bread or buns.

GRAINS IN INDONESIAN CUISINE

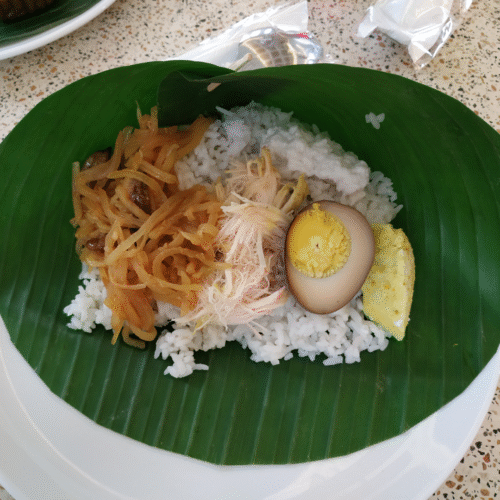

Rice is a staple for all classes in Indonesia and occupies a central place in culture: it shapes the landscape, is sold at markets, and is served in most meals both as a savoury and a sweet food. Rice occupies almost one-third of the daily ration. 98% of Indonesian households consider it the main staple. Rice isn’t always cooked elaborately; people often just eat plain rice with a few sides. But even the simple rice dishes show how creative locals get with this staple:

– nasi uduk rice cooked in coconut milk

– nasi kuning rice with coconut milk and turmeric

– ketupat rice steamed in woven packets of coconut fronds

– lontong rice steamed in banana leaves

– intip or rengginang rice crackers

– nasi goreng – the fried rice. Nasi goreng is omnipresent in Indonesia and considered a national dish. It’s a dish of stir-fried rice pre-boiled and then cooked with palm oil, spiced with kecap manis, shallot, garlic, ground shrimp paste, tamarind, chilli, and accompanied by egg, chicken, or prawns. Nasi goreng has expanded beyond its regional origins, gaining popularity in Sri Lanka, as well as in Suriname and the Netherlands through Indonesian immigrant communities.

Noodles are a popular staple and comfort food across Indonesia, consumed at all times of day, as well as rice. Popular are mie goreng (fried noodles), mie ayam (chicken noodles), kwetiau goreng (stir-fried flat rice noodles), and laksa (noodle soup with spicy coconut broth).

Wheat is not native to Indonesia; it got here through the Chinese and the Dutch. Indonesians acquired a taste for Chinese wheat noodles, Indian roti, and Dutch bread. Yet in Indonesia, rice is such a habit that even noodles are consumed with rice. Wheat consumption reached a new high after the advent of instant noodles in the 1970s. Since then, Indonesia has become its major producer and consumer.

PRODUCE IN INDONESIAN CUISINE

Vegetarian food is easy to find in Indonesia. Cuisine uses vegetables in many ways, and sambal, coconut, or peanut sauces make them vibrant and not boring: gado-gado (salad of boiled veggies), karedok (raw veg salad with peanut sauce), lalab (raw veggies with sambal), urap (mixed steamed veggies with spiced coconut dressing).

Though many iconic dishes use vegetables, data shows lower veggie consumption than the global average (which is ~200 g/day); quantities eaten daily are generally small. The plate is filled mainly with rice, and the rest is just a touch of vegetables and protein. Also, veggies are mixed with coconut, peanut sauce, sambal, or tempeh, so the flavor is strong, but the portion sizes of the vegetables can be modest. When consumed, water spinach, regular spinach, long beans, eggplant, chayote, cucumber, and bitter melons are frequent choices.

Starchy roots, though, are big in Indonesia, especially cassava and snacks, crackers, and flour-based street foods made of it. Cassava leaves are one of those everyday Indonesian foods that outsiders rarely notice. They’re slightly bitter and earthy, somewhat like spinach but firmer and fibrous. When stewed in coconut milk (gulai daun singkong), the bitterness mellows, and they take on a creamy, savory flavor. Cassava leaves are very frequent in Sumatra, Java, and Kalimantan in homes and street food stalls. Together with rice, sambal, tempeh, and fish, they are a great daily meal combo.

Alongside cassava leaves, papaya leaves, melinjo leaves, katuk leaves, and sweet potato leaves are also widely consumed, though they may not be familiar to Western diets. In everyday cooking, they are usualy stir-fried with garlic or chilies.

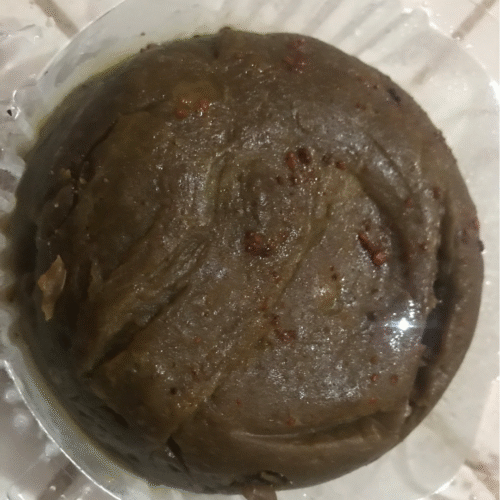

Indonesia is unique as the birthplace of tempeh, a fermented soybean product, an affordable protein. It’s even higher in protein, fiber, and vitamins than tofu. Compared to meat, tempeh has a very low carbon footprint and is a great plant-based meat substitute. Though a “humble food” in Indonesia, once linked with the poor, today it’s gaining global recognition as a superfood. It’s not as bland as tofu may be; tempeh has a nutty, mushroomy, umami taste and a firm, chewy texture that holds up. Traditional local tempeh dishes are tempeh goreng (deep-fried slices, crispy snack), orek tempeh (spiced, caramelized tempeh strips), sayur lodeh (vegetable coconut stew with tempeh).

Oncom is a lesser-known, also fermented Indonesian staple. It’s closely related to tempeh; both are fermented using mold, but oncom is made from the by-products of other foods: soy pulp remains from making tofu, peanut remains after the oil has been pressed out, and cassava tailings when extracting the starch. This makes oncom a very sustainable protein source. At the same time, the flavor is earthy, mushroomy, and can really be an acquired taste.

A staple in eastern Indonesia, but not common in Java or Sumatra, is sago – pure starch, extracted from sago palm stem, low in protein and vitamins, but a vital calorie source in non-rice regions. A sticky, glue-like porridge is made from sago in Papua and Maluku, and sago flour is also turned into flatbreads, crackers, and pearls (similar to tapioca pearls).

MEAT IN INDONESIAN CUISINE

Meat consumption is moderate as it’s still relatively expensive for the average consumer. Protein comes from tempeh and tofu, seafood, eggs, and occasionally meat. When consumed, the most popular are chicken, beef, goat, water buffalo, duck. Pigeon, quail, and wild swamp birds are also consumed, but pork is low, as the country is predominantly muslim.

Indonesians breed free-range chickens in the villages. Compared to mass-farmed chickens, these village chickens are thinner, and their meat is firmer. About 60% of chicken production is concentrated in Java, so its logistics are pricey to distribute to more remote areas, thus the access is even lower.

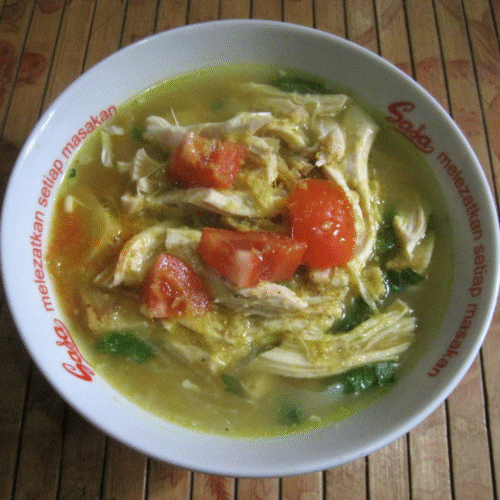

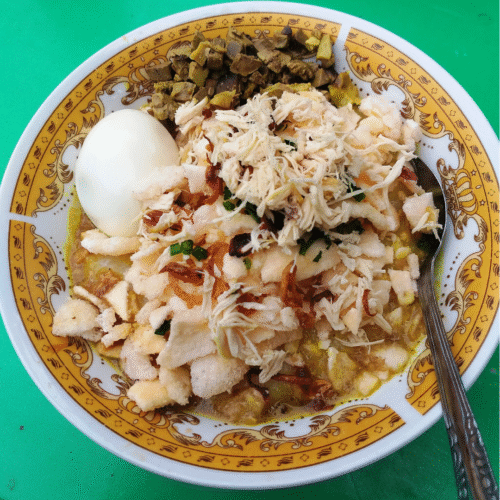

Various fried and grilled chicken recipes exist throughout the country. Other than fried or grilled as satay, chicken might be added as soup, such as sup ayam or soto ayam, or simmered in coconut milk as opor ayam. Chicken feet are enjoyed in many countries, but they are particularly popular here as a street staple. If interested, look for soto ceker, chicken foot soup, or kripik ceker, chicken feet crackers.

When most people think of curry, they’re picturing Thai green curry or Indian curries. Indonesian meat curries represent a different approach – they’re not about balancing heat and cooling (like Thai), building layers of spices (like Indian), or showcasing fresh herbs (like Vietnamese), but about transformation. Indonesian curries take tough cuts and turn them into something transcendent through patient reduction, complex spice work, and an understanding of how fat, acid, and sugar work together. Indonesian cooks don’t just add coconut milk – they reduce it. Like, for example, gulai, Indonesia’s foundational curry. The coconut milk gets simmered down until the oils separate, and the spice paste is fried, creating a concentrated flavor. This reduction, called pecah minyak – oil breaking, is fundamental and creates this rich, almost creamy texture without any dairy. Indonesian curries embrace the sweetness-savory quite strongly. Palm sugar is not just a background note – it’s a primary flavor component that’s so Indonesian. Let’s illustrate this with rendang, the most famous Indonesian curry, a UNESCO national heritage dish. It starts with a spice paste of coconut milk, lemongrass, galangal, garlic, turmeric, ginger, chilies, and spices and beef (traditionally water buffalo, but good luck finding that at your local grocery store), and gets braised for hours, sometimes up to eight, until the liquid evaporates and the meat becomes fork-tender and coated in a dark, concentrated spice crust. The secret is patience and proper browning.

I bet everybody knows the delicious satay skewers, but only a few trace them to their Indonesian origin. Satay is a dish traced to Java in Indonesia, believed to have developed during the 19th century. The combination of grilled skewers and peanut sauce spread widely, first across Indonesia and then Malaysia, Singapore, and Thailand. Indonesian satay uses beef or goat due to the Muslim majority, while in Thailand, pork satay became popular, and the peanut sauce tends to be sweeter. Satay has since become a quintessential street food in many Southeast Asian countries. Indonesia alone has over 250 different recipes.

FISH AND SEAFOOD IN INDONESIAN CUISINE

With the world’s second-longest coastline, fish is a key daily protein. Indonesian fish dishes go beyond simply emphasizing the “natural taste” of fish. A popular dish is grilled ikan bakar, which uses turmeric, garlic, and lemongrass with the goal of creating a balance between the freshness of the fish and the nuances of spices. Frying whole fish is also common but involves a light starch coating, allowing flesh to remain crispy yet tender inside. Fried fish is often paired with sweet kecap manis. Indonesian steamed fish in banana leaves has subtle, earthy flavors; the dish preserves moisture and freshness. It asks to be paired with steamed rice, sambal, and lalapan salad as a side.

Popular seafood in Indonesian cuisine includes skipjack tuna, tuna, mackerel, pomfret, wahoo, milkfish, trevally, rabbitfish, abalistes, amberjacks, rastrelliger, yellowtail scad, nemipterus japonicus, John Dory, garoupa, red snapper, anchovy, swordfish, shark, stingray, squid or cuttlefish, shrimp, crab, blue crab, and mussel.

INSECTS IN INDONESIAN CUISINE

Unlike Thailand, in Indonesia, insects are not a popular ingredient, nor are they widely available as street food. In Java, locals do catch, bree,d and sell certain species of insects, usually sold alive as pet bird feed. Nevertheless, several cultures in Indonesia consume grasshoppers, crickets, termites, and the larvae of sago palm weevils, bees, and dragonflies. In Java and Kalimantan, grasshoppers and crickets are lightly battered and deep-fried in palm oil.

EGGS AND DAIRY IN INDONESIAN CUISINE

Eggs are an important protein staple. One signature Indonesian way to do eggs is telur pindang, a method where eggs are boiled in water mixed with salt, soy sauce, shallot skins, teak leaf, and spices. This process colors the eggs a dark brown but also extends their shelf life.

Fresh dairy milk consumption is limited; Indonesia is not known for mass dairy farming. Several unique traditional dairy products exist, mostly from water buffalo milk: minyak samin, a butter-like product similar to ghee; dadih, a yogurt-like fermented milk product from West Sumatra; bagot ni horbo, cheese-like products from North Sumatra made from coagulated buffalo milk. In cooking, coconut milk is much more prominent than dairy milk.

NUTS, OILS, AND DESSERTS IN INDONESIAN CUISINE

Thin, thick, coconut milk, and coconut cream largely fulfill the dairy role. Candlenuts are a distinctive ingredient of Indonesia, with high oil content, which, when cooked, integrate seamlessly, enriching the mouthfeel. They are important in making rempah (wet spice pastes). Candlenuts are never eaten raw and are never used as snacks; their use is strictly culinary.

A careful reader may have noticed that many dishes feature the word goreng, meaning fried. This method, using locally produced palm oil, ranges from light pan-frying to deep-frying in generous amounts. Nowhere is this frying culture more evident than in the category of snacks called gorengan – a generic term encompassing Indonesia’s fritters. These popular street food treats can be savory or sweet; they feature an egg batter combined with various bananas, tempeh, tofu, sweet potatoes, or jackfruit, or fish.

Indonesians often eat sweets as a snack throughout the day, as a social food with family and friends. Indonesian desserts are distinct in the use of tropical ingredients and unique textures. They focus on the natural sweetness of palm sugar, coconut milk, glutinous rice, durians, jackfruits, and mangoes. One defining characteristic is the frequent use of coconut milk.

Another unique feature is the prevalence of glutinous rice or sticky rice. Traditional klepon (sweet rice balls filled with palm sugar and coated in grated coconut), lupis (sticky rice cakes wrapped in banana leaves served with coconut and palm sugar syrup), and kue lapis (layered steamed rice flour cake) show chewy, sticky, and luscious textures. Pandan leaves for flavor and color also distinguish Indonesian sweets.