THE ESSENCE OF BRAZILIAN CUISINE

If you sit down at an everyday Brazilian table, it’s not one fancy dish that stands out, but rather reliable basics: grains, beans, cassava, fruits, and coffee – presented with a sense of plenty. Rice and beans appear at almost every meal – they’re the foundation that everything else builds on. Add some beef, chicken, or fish – though the meat doesn’t always take center stage. Sure, Brazil’s famous churrascarias (barbecue houses) with their parades of grilled meats get all the attention abroad, but that’s hardly the whole picture of Brazilian food. Plenty of Brazilian home cooking focuses on vegetables, grains, and plant-based dishes.

Vegetables and salads are always present, but in a straightforward way, with no complex preparations. Starches beyond rice are important: cassava (manioc) in all its forms, which lends meals a distinctly Brazilian texture. Bananas, papayas, mangoes, and oranges are so common that fruits often feel less like dessert and more like a natural extension of the meal. Bread matters too. A warm pão francês (short bread roll) is essential for breakfast and afternoon snacks. And of course, there’s coffee – a small, strong, very hot, and with plenty of sugar.

GRAINS IN BRAZILIAN CUISINE

On the daily Brazilian table, grains are the quiet constants. Rice is an everyday food – just lightly seasoned and boiled – and almost always combined with beans into a complete, nourishing base.

Corn is a big deal, especially in the Northeast, from street snacks to festivals, like for example in Festa Junina (Brazil’s June harvest festival), where corn is the star ingredient. Some corn everyday staples are:

- Pamonha – like a Brazilian tamale, corn paste steamed in husks.

- Canjica – a sweet porridge made from hominy corn with milk, sugar, and spices.

- Curau – a creamy corn pudding.

- Cuscuz de milho – a fluffy steamed corn cake, common at breakfast in the northeast.

Brazil may be famous for rice, corn, beans, and cassava, but wheat, mainly as bread, is the daily staple. The small crusty roll pão francês (Brazilian French bread) is eaten every day across the country, so much so that São Paulo alone bakes 18 million of them daily, outnumbering residents.

Brazil has a big pasta and pizza culture, inherited from European immigrants, but now completely ‘Brazilianized’ with unique toppings like catupiry processed cheese, green peas, corn, or hearts of palm. In Brazil, pasta is often eaten as a main rather than as a first course like in Italy. It’s also common to serve rice alongside pasta dishes, something that might surprise Italians!

PRODUCE IN BRAZILIAN CUISINE

Potatoes, sweet potatoes, and yams are everyday staples, but they came from the Andes and were introduced to Brazil by the Portuguese in the 16th century, after the Spanish spread them from Peru into Europe. At first, potatoes weren’t a major staple, and even today, they have never reached the same level of importance as corn or cassava.

It’s very energy-rich – high in carbohydrates, but low in protein and fat. In Brazil, it is both homegrown and cultural, so it shows up everywhere. It is toasted into farinha (cassava flour) for sprinkling on meals, pressed into tapioca (cassava starch) for crepes, or simmered into stews. It is also turned into farofa, a coarse side dish with a mild flavor, similar to breadcrumbs, that absorbs the taste of added ingredients like pork, onions, and herbs. Farofa is a salty and savory staple often served with feijoada (bean stew), barbecued meats, and rice and beans. What’s particular is how cassava isn’t just a side ingredient – it’s a texture and flavor marker that gives Brazilian food its own character.

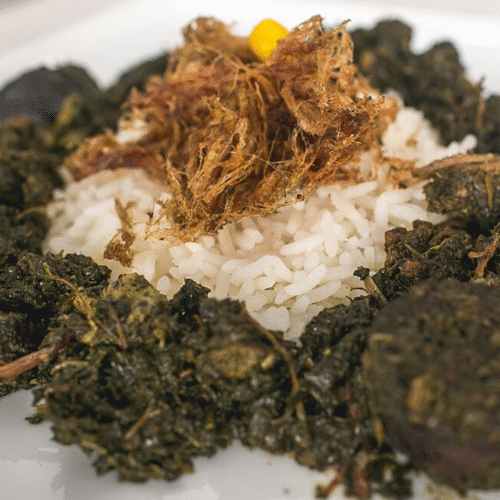

Feijoada, the rich black-bean and pork stew, is hailed as Brazil’s national dish. The word comes from feijão (bean in Portuguese), underscoring that beans – not meat – are the foundation. A common myth says feijoada was invented by enslaved Africans using leftover pork cuts. Historians show it’s actually adapted from European bean-and-meat stews like the Portuguese cozido and French cassoulet, later ‘Brazilianized’ with black beans. Traditionally, it included inexpensive cuts: pig’s ears, feet, tails, and trimmings. Today, it’s made with sausages, pork ribs, or dried beef carne seca.

Pumpkins, okra, and leafy greens (collard greens, kale) are important. Pumpkin is common in stews and soups; okra, introduced through African traditions, thickens dishes like caruru (a zesty, shrimp stew); and collard greens are the classic side for feijoada. These vegetables aren’t highly spiced or complex on their own – they’re valued for body, comfort, and how they complete the plate.

Fruits are very visible – more so than in many other cuisines. Because of Brazil’s tropical climate, the country has an enormous variety of fruits, from everyday simples to exotic Amazonian species. Fruit is a part of the daily meal: a slice of papaya, mango, or orange at breakfast is almost expected. Many Brazilians will slice a banana and eat it alongside rice and beans. It’s not universal, but it’s a well-known habit, especially in home cooking and school lunches.

Coconut and pineapple flavor sweets, cakes, and puddings; bananas and raisins are mixed into savory farofa; cupuaçu (a tropical fruit native to the Amazon, closely related to cacao) and açaí (a small, dark purple berry) become creamy desserts. In the Amazon, açaí, bacaba, and tucumã (both palm fruits) are essential to regional diets, eaten daily in bowls, porridges, or savory accompaniments. Açaí na tigela (açaí bowl) has surged online and become a global phenomenon. Fresh juices are very popular from passionfruit, guava, cashew fruit, and acerola (a small red fruit, Barbados cherry).

MEAT IN BRAZILIAN CUISINE

Brazil stands out in its sheer connection to livestock, though cattle aren’t native to South America. Cattle arrived with the Portuguese in the 1500s. From there, animals adapted incredibly well to the continent’s grasslands and warm climate, and that’s what made them take off. Cattle spread inland as settlers moved away from the coast. Northeast and later the wide open savannas of the Cerrado became grazing areas. I the far south, the gaúcho cowboy culture developed around herding. By the 20th century, Brazil’s sheer land size allowed it to become home to one of the largest commercial cattle herds in the world.

Not only do Brazilians have a big barbecue culture, but they also use every possible cut of the animal: ribs, tails, and organ meats. However big Brazilians’ love of barbecue may be, in the context of neighbouring cuisines, they still eat more beans, rice, and cassava with their meat than their Southern Cone neighbors.

Culturally, meat is also tied to celebration. The rodízio style of dining – endless skewers of grilled beef, sausages, chicken hearts, ribs, served at churrascarias – has become one of Brazil’s global exports, a statement of hospitality and plenty.

In many countries this cut is trimmed off or ground into hamburger, but Brazilians grill it in thick slabs, with just coarse salt, savoring its fat cap and tenderness. It’s iconic because it shows how Brazil gave a new identity to a humble cut that wasn’t valued the same way elsewhere. For Brazilians, picanha represents simplicity elevated.

Beef has the cultural prestige of churrasco and cattle ranching, but chicken feeds masses daily. Brazil is not only the world’s largest beef exporter, but also the world’s #1 chicken exporter. It might sound ordinary, but roast chicken frango asado is iconic in Brazil because it’s the family meal of choice.

Goat in Brazil is eaten mainly in the Northeast, where goats thrive better than cattle. Mutton is less common nationally, but present in the Northeast and the South. Pork is far more widespread than goat or mutton, used in sausages (linguiça), ribs, and roasts. Pork fat was historically important for cooking before vegetable oils became common. Today, Brazil is one of the world’s top pork producers and exporters.

FISH AND SEAFOOD IN BRAZILIAN CUISINE

Fish and seafood are important, but more regional proteins. Along the Amazon and Northern rivers, fish is eaten at nearly every meal, often replacing red meat entirely. Local fish species like tambaqui, pirarucu, and tucunaré are grilled, stewed, or cooked in tucupi (fermented manioc broth).

Most internationally visible seafood come from Afro-Brazilian cuisine, the Atlantic coast. In Bahia, moqueca – a slow-cooked fish or shrimp stew with coconut milk, dendê oil (type of palm oil), and peppers – is one of Brazil’s most famous seafood dishes, tied to Candomblé (local religion) rituals. Shrimp also appear in acarajé and vatapá:

- Acarajé – deep-fried black-eyed pea fritters, split open and stuffed, most famously with vatapá.

- Vatapá – a rich, creamy paste made with bread, shrimp, coconut milk, peanuts, and palm oil. It’s intensely flavorful.

In the Southeast, salted cod bacalhau brought by the Portuguese remains central to festive meals, especially around Easter and Christmas.

MILK AND DAIRY IN BRAZILIAN CUISINE

Milk and dairy in Brazil don’t shout the way meat or beans do, but they are steadily consumed every day. Brazilians are big milk drinkers – warm milk with coffee is a breakfast or evening ritual. Cheese in Brazil is less about aged (like in Europe), but more about fresh and mild varieties. Fresh white cheeses queijo minas (fresh or semi-cured cheese) or coalho (semi-hard curd cheese) are part of breakfast spreads, stuffed into breads.

Pão de queijo – Brazil’s cheese bread – is small, round, chewy on the inside, lightly crisp on the outside, and packed with cheese flavor. The secret is that it’s made not with wheat flour, but with tapioca starch from cassava, which gives it that elastic, airy texture you don’t find in regular bread. Over time, it became a staple snack across the country.

Condensed milk is practically its own food group – it’s the base of brigadeiros (bite-sized chocolate fudge balls), flans, and puddings. This is something quite particular to Brazil: while many countries use condensed milk occasionally, in Brazil, it has become the backbone of dessert culture.

NUTS, OILS AND DESSERTS IN BRAZILIAN CUISINE

Nuts in cuisine are not as central, although the country is home to the famous Brazil nut (castanha-do-pará). It’s less of an everyday kitchen ingredient and more of a symbol sold at markets, eaten plain, or exported. In the Amazon region, though, it’s more present.

Another important one is the cashew nut. Both the nut and the cashew fruit (caju) are used – the nut in sweets, savory dishes, or as a snack, and the fruit in juices and desserts. In Afro-Brazilian cuisine, particularly in Bahia, peanuts are more important. They’re ground into creamy bases for vatapá (savory paste-like stew) and caruru (okra stew), along with coconut milk and palm oil. Peanuts also feature sweets like paçoca (a crumbly peanut candy) and pé de moleque (peanut brittle).

Dendê oil is a type of palm oil, but very specific to Brazil and has its own identity: it’s unrefined and aromatic, of thick, deep orange-red color, and has a strong, earthy, almost smoky flavor. In Brazilian cooking, it’s not just another cooking fat – it’s a defining ingredient. Fish stew moqueca, acarajé, vatapá, and caruru wouldn’t taste the same without dendê.

Brazilians love their desserts simple, rich and satisfying, often built around condensed milk, chocolate, coconut, or tropical fruits. Texture-wise, expect chewy bites (pão de mel, coconut candies), creamy puddings (pudim de leite), and airy cakes soaked in sweet milk (bolo de rolo or bolo de fubá). Street fairs and birthday parties always have trays of small, bite-sized treats – not elegant pastries, but colorful, homemade, and meant for sharing.