THE ESSENCE OF AZERBAIJANI CUISINE

Azerbaijani cuisine sits at the crossroads of Europe and Asia, pulling flavors from Persian, Turkish, and Russian traditions into something distinctly its own. Rice is everything here, especially pilaf. They’ve perfected around 200 different versions of it. Walk into any Azerbaijani home and you’ll notice the sheer volume of fresh vegetables and herbs on the table: eggplants, tomatoes, peppers, and piles of fresh greens. Lavash flatbread comes with every meal, used to scoop and wrap whatever you’re eating. Soups matter deeply in this cuisine. More than 30 regional varieties exist, each one tied to a specific place and season. Lamb and mutton are the meats people crave most, often paired with yogurt or tangy fermented milk drinks that cool things down. Dried fruits and nuts show up in both savory dishes and desserts, adding sweetness and crunch where you least expect it. Every meal ends the same way: black tea in those distinctive pear shape glasses, sweetened with spoonfuls of candy-like fruits.

GRAINS IN AZERBAIJANI CUISINE

There’s a fascinating dichotomy in Azerbaijani cuisine! Rice is often mentioned as the staple grain, yet wheat is consumed tens of times more. A versatile and substantial wheat provides sustenance; rice is more for special occasions. Wheat appears in noodles, bulgur pilafs, flat and leavened breads.

Bread, a symbol of prosperity and respect, is never to be wasted. Traditional bread is cooked in large griddle pan saj or in a clay oven tandir, where charcoal at the bottom creates intense heat and the dough is kneaded into an oval and stuck to the side. When ready, a hook retrieves the bread from the tandir. Other breads range from delicate, paper-thin sheets of lavash to robust, round, whole-wheat Russian-style loaves such as karpij choral (brick bread), agh choral (white bread), gara choral (black bread), and yucca, made with dough and yogurt or buttermilk.

Azerbaijan’s national dish, pilaf or plov, has at least 40 documented recipes and countless undocumented variations. Plov consists of three components served simultaneously: rice, gara (fried meat, dried fruits, eggs, or fish), and aromatic herbs. The most lavish and luxurious is shah plov, encased in a baked flatbread cocoon, served at weddings and New Year’s. When you cut it open at the table, the rich, aromatic mix spills out — almost like a crown being revealed. Sour drinks usually accompany plov: ayran, black tea with lemon, or verjuice.

PRODUCE IN AZERBAIJANI CUISINE

Vegetables are visible, valued, and widely available in Azerbaijani home cooking. They are often stuffed with meat and rice to make dolmas, a typical dish across the Middle East. Azerbaijani dolmas are smaller and rounder than elongated dolmas in Turkey and Greece. They often prioritize lamb over other meats and incorporate beans, lentils, and bulgur.

Pickled vegetables turshu are very common and culturally important, served as appetizers and side. Turshu shows up with most meals, especially in winter: cucumbers, cabbage, eggplant, tomatoes, peppers, even fruits like plums and quince.

Azeris love grilling or pan-frying vegetables on their own. Eggplant, tomatoes, peppers, and mushrooms get charred until smoky or sautéed until soft, then served as sides or scattered across a spread. The whole approach depends on quality produce and light seasoning, nothing fancy. You’ll also find vegetables in gentle braises, cooked with herbs and a touch of sourness. Greens mixed with herbs get tucked into stuffed flatbreads, often with yogurt for dipping. But plenty of vegetables arrive completely raw and unadorned. Tomatoes, cucumbers, radishes, and fresh herbs land on the table sliced and visible, treated as essential parts of every meal.

When Azerbaijan was a part of the Soviet Union, rice – traditionally cultivated in the foothills of the Caucasus – gave way to potato in agriculture and in cuisine. Potatoes were popularized comparatively late, so only a few traditional dishes are centered around them.

Azerbaijanis creatively use pomegranates, peaches, apricots, figs, plums, cherries, and citrus fruits in savory dishes and desserts. Pomegranates are very special, used in a unique Azerbaijani sauce known as narsharab. Fruit preserves, known as murabba, are an accompaniment to tea.

MEAT IN AZERBAIJANI CUISINE

The sizzling of grilled skewered meat is common across the Caucasus. Like their neighbors, Azerbaijanis strongly prefer lamb and mutton, from which they make kebabs. Azerbaijani kebabs are usually simpler and less spiced than Turkish ones, with bigger chunks of meat threaded onto the skewer. The meat is marinated with onions and something sour, like vinegar or pomegranate juice. That approach overlaps with Armenian traditions, but in Azerbaijan, there’s a stronger focus on tart, fresh acidity.

Cities have increasingly preferred beef in recent decades. Pork consumption remains minimal due to Islamic traditions, contrasting with Georgia and Armenia, where pork is popular. The coastal regions incorporate more poultry and fish into their diet. Game, while present in traditional Azerbaijani cuisine, is less popular than in Georgia.

Azerbaijan still maintains traditional husbandry in rural areas, which affects how meat is produced: every part of the animal’s body is used, tail fat adds richness to dishes, and the casings are used for sausages.

Preservation of meat is unique. Historically, large chunks of lamb were strung up and dried for 24 hours, then salted, stewed, and fried in oil. Meat was then transferred into ceramic jars and covered in melted butter or mutton fat. After four to eight weeks, it was ready to eat. This method, known as govurma, is still used. govurma shorbas (lamb stew) uses this aged meat combined with beans and potatoes.

FISH AND SEAFOOD IN AZERBAIJANI CUISINE

Fish and seafood in the country are deficient, as historically, meat was more of a preferred protein source for nomads and herders. Of seafood species found in the Caspian Sea, sturgeon is valued, mostly for caviar. The black pearls have long been a symbol of luxury and opulence for their rich, buttery flavour and delicate texture. Sturgeon fishing was a vital part of the sea economy, but overfishing and habitat degradation have dramatically reduced these populations. Azerbaijan and other coastal nations are implementing stricter regulations and exploring sustainable practices, such as aquaculture, to preserve sturgeon. One innovative approach is the Baku Caviar brand, which, for every jar sold, releases 10 sturgeon fingerlings into the Caspian Sea to help restock the ecosystem.

Kutum, a Caspian whitefish, remains one of the most respected traditional fish. Carp from rivers and inland waters is also common, and smaller fish like kilka and sprat tend to be more affordable and everyday. Grilling is common, especially fish kebabs, often seasoned simply and served with herbs or something sour. Baking and pan-frying are also typical, with finishes that include pomegranate juice, sour plum paste, or fresh herbs to add acidity and balance. One of the most distinctive is fish lavangi; fish is stuffed with walnuts, onions, herbs, and then baked.

MILK AND DAIRY IN AZERBAIJANI CUISINE

Dairy products are essential and there is a notably wide range of fermented dairy products. Alongside raw, milk is consumed in form of butter, cream, sour cream, yogurt, cottage cheese, buttermilk, dovga (yogurt soup), ayran (fermented milk drink), qatiq (fermented milk product, more solid form of yogurt than ayran), and suzme (creamy, fatty dairy product made from filtered and thickened qatiq).

Cheese is not as spread in Azerbaijan as in other Caucasian cuisines, but the known varieties are truly unique. For instance, the motal pendiri cheese, made from unpasteurized sheep or goat milk, is curdled with rennet, salted, and packed into a sheepskin sack, sometimes with the hairy side in! They are then aged in a cool, damp place, resulting in tangy and sour delight.

DESSERTS IN AZERBAIJANI CUISINE

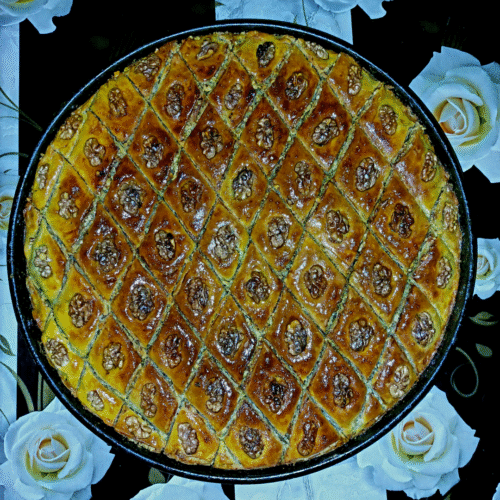

Azerbaijani desserts are often pastries, which extensively use butter and clotted cream, known as qaymaq. Pastries can also be layered with flaky dough, filled with chopped walnuts or almonds, and drenched in syrups or honey. This combination creates a textural contrast between the crisp layers and the gooey fillings. Cardamom, vanilla, and saffron frequently flavor local desserts. Many desserts require precision and skilled hands, particularly those involving delicate syrups or the handling of phyllo pastries.