THE ESSENCE OF ALGERIAN CUISINE

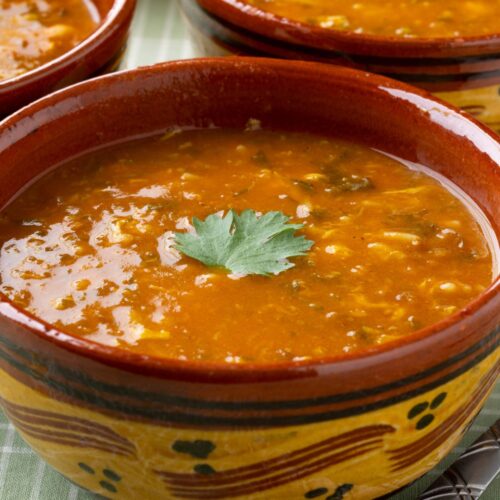

Algerian food varies by region and season, but it is largely plant-based, with vegetables and cereals at its core. Many dishes center on bread, dairy products, olive oil, and fresh spices, including vegetable soups, salads, tajines (slow cooked dish in a conical clay pot), couscous, and sauce-based meals. In Algerian cooking, sauce-based meals are everyday staple. Ingredients simmer slowly in a tomato and onion sauce flavored with spices, olive oil, and herbs. The sauce is meant to be soaked up with bread or served over couscous.

Meat is scarce in many poorer or rural areas. Still, it is extremely significant during family gatherings and holidays.

Typical Algerian breakfast includes homemade bread or French-style pastries, honey-soaked pancakes bahrir, sweet Spanish churros reminiscent sfenj, white cheese, seasonal fruits, sweet mint tea or strong Arabic coffee, spiced with cardamom. Lunch is a substantial meal shared by the whole family, and it is typically couscous, stews, chorbas (soups), and semolina pasta dishes. Dinner choices are similar to lunch unless guests alter the menu with specialties like mechoui, a spit-roasted lamb, meat tagines with dried fruits, meatballs kefta, salad, and harira chickpea soup.

In Algeria, it’s a common tradition to symmetrically arrange couscous, pasta, rice, and top it beautifully with vegetables, meat, and sauce. This presentation not only makes appeals, but it also ensures that all the flavors are well distributed throughout.

GRAINS IN ALGERIAN CUISINE

Foods deriving from durum wheat (high protein and high gluten variety) are the most common. Bread is thought to be a God’s blessing, a symbol of life, fertility, and abundance. Common breads are:

- khubz, a round, a few centimeters thick bread

- kesra, a semolina flatbread with oil, salt, and water;

- batbout, a round, thick bread good for stuffings;

- and the French baguette.

Algerians produce traditional durum wheat pasta. Rechta is a popular pasta dish, a specialty in Algiers and Constantine cities. The exact origin of rechta is not well-known, but it is likely a result of Berber traditions blended with Arab, Ottoman, and Italian influences. Similar to rechta, tlitli (meaning bird’s tongue) is to another pasta, the form of small, rice-shaped grains often served with chicken and tomato sauce.

A staple in North African cuisines, an intangible cultural heritage recognized by UNESCO, and a national dish of Algeria is couscous – steamed semolina granules of durum wheat, served with a spiced stew. Great care is needed to properly cook couscous: granules are placed in a special steaming couscoussier, removed into a large bowl after first steaming, fluffed up with a bit of oil or butter multiple times, then returned to the couscoussier for additional steaming. While the couscous steams, the sauce is prepared from lamb, chicken, fish, carrots, zucchini, chickpeas, or tomatoes. Once both the couscous and stew are ready, the meal is served on a large platter, shaped into a mound with a well in the center. All this preparation is truly time-consuming, but it also brings families together.

Frik (sometimes spelled freekeh or farik) is green wheat harvested while still young, then roasted, dried, and threshed. This process gives distinct smoky flavor and slightly chewy texture. Frik dates back thousands of years, with its production method used to preserve wheat and enhance its taste. It’s considered a whole grain and is highly nutritious, rich in fiber, protein, and vitamins. Here in Algeria, it is particularly famous for its use in chorba frik soup, salads, and as a side dish similar to rice or bulgur.

Barley, a resilient grain, is important in arid climates; it is used in soups and porridges as a hearty and nutritious base. Barley flour are mixed with others for breads, cereals, and barley couscous.

Corn is not a traditional staple, but was adapted due to economic factors, availability, and global food trends.

PRODUCE IN ALEGERIAN CUISINE

Algerian dishes often start with a base of vegetables: sautéed onions, garlic, and tomatoes to provide a deep flavor foundation. Zucchinis, eggplants, carrots, peppers, and broad beans are the most popular, as they feature the majority of stews, tagines, and couscous. Preserved vegetables – pickles or prepared with salt and spices – are common in Algerian pantries, like for example hot peppers preserved with salt, garlic, coriander and turmeric. in Algeria. Pickling spices include cumin, coriander, chili flakes, and sometimes a hint of cinnamon or clove, garlic, and dill.

Dates, figs, pomegranates, grapes, loquats, oranges, lemons, and melons refresh during the hot months. Dried dates, figs, apricots, and raisins are integral; they’re combined with almonds, pistachios, and walnuts in couscous, tagines, and pastries. Algeria is sometimes called the country of cherries and dates (standing 4th in global dates consumption – 23 kilos per person per year).

MEAT IN ALGERIAN CUISINE

In Algeria’s steppe and Saharan regions, mutton and camel have long been the traditional meats. These areas, known as “the land of the sheep and the dromedary,” were once centers of sheep and camel farming, though poultry and beef are now becoming more common. Camel meat remains negligible at the national level, but its consumption, especially when it’s young, in those Saharan regions, is significant. Sheep meat is festive; slaughtered collectively, it constitutes a cultural identity for the Algerian people.

A very special Maghrebi barbecue is mechoui – a whole sheep, lamb, or goat spit-roasted whole over a pile of embers. After having slaughtered and dismembered the young lamb, all the organs are removed, with the exception of the kidneys. This cavity is sprinkled with the luxurious ras el hanout spice mix and stitched. Méchoui is served at the beginning of the meal; using the fingers of the right hand, the host takes pieces of meat and offers them to guests. Traditionally, no cutlery is used because, due to the slow cooking, the meat should be able to detach without any effort.

Algeri, as well as all the North African cuisines, have a tradition of tagine, both the conical clay cooking vessel and the stew cooked in it. Heavily spiced lamb, beef, or chicken is slow-cooked with vegetables, dried apricots, raisins, prunes, and dates are often added as well. The tagine’s conical shape retains moisture while cooking, so the ingredients turn out exceptionally tender.

Another traditional way to prepare meats is chtitha, ‘little dance,’ which indicates its spiciness. This is a family of dishes, originally of the tajine type with a base of chickpeas and chicken (but any protein goes), cooked in a red sauce, heavily seasoned with Algerian condiment derssa.

Algeria’s offal tradition is big. The berkoukes, a hearty tripe stew served with small pasta, show how Algerians transform humble ingredients into comfort food. Their version of cooked sheep head requires skill to prepare and knowledge to eat. Its the dish shared among family members who know which parts are considered the most delicious (brain, tongue, and cheeks). Algerian street vendors are very skilled in their signature kebda meshwiya (grilled liver) and klawi (grilled kidneys) – all quick meals served with fresh bread.

FISH AND SEAFOOD IN ALGERIAN CUISINE

Algerians eat fish and seafood, though less extensively than Tunisia or Morocco. Consumption varies. Coastal areas offer sardines, mullet, sea bream, octopus, cuttlefish, and shrimp. Sardines, in particular, are cheap, accessible, grilled or cooked in spicy tomato sauces. Inland and Saharan regions traditionally eat little or no fish.

Algerians usually season fish simply but boldly, often marinating it with chermoula, a blend of garlic, paprika, cumin, coriander, parsley, lemon, and olive oil.

Islam doesn’t restrict seafood consumption, so there’s no religious limitation. However, fish historically carried an image of being “poor man’s food,” especially sardines. Urbanization and improved cold storage have expanded access to seafood inland, and Algerian restaurants now serve more Mediterranean-style seafood dishes.

MILK AND DAIRY IN ALGERIAN CUISINE

Algeria consumes most milk across North Africa. Algerian cuisine has two fascinating fermented dairy products: leben and raïb. Both are born back in pre-refrigeration days when fermenting milk was a clever tactic in the North African heat. Leben, a tangy drink akin to kefir, refreshes during scorching Algerian summers, while raïb, its thicker, yogurt-like cousin, is used as a condiment or in cooking. They are both consumed during Ramadan at the iftar (fast-breaking evening meal).

Before the French colonization, Algeria had a tradition of fresh goat and sheep milk cheeses made by nomadic tradition. The French colonization significantly impacted dairy: they introduced advanced cheese-making, commercial dairy farming, and European camembert, brie, and roquefort to Algeria. Today, about 80 percent of milk comes from cattle.

Klila is a fermented extra-hard cheese and unique artisanal dairy made from goat or sheep milk leben. During heating, the milk curdles and is then drained in muslin. After sun-drying, the cheese develops a crumbly texture and long shelf life, lasting without refrigeration — ideal for nomadic lifestyles. Klila has a delicate, tangy flavor and is often served crumbled over dishes.

NUTS AND DESSERTS IN ALGERIAN CUISINE

Algerian desserts are broadly characterized by their sweetness of honey or syrup. In Algerian culture, as in many parts of the Arab world, offering sweets is a way to honor guests, show them respect and warmth. Over time, this tradition has influenced the particularly high sweetness in desserts, passed down through generations, and become part of the national palate. People grow up with these flavors and associate sweetness with comfort and tradition.

Almonds, pistachios, walnuts, dates, and figs are staple ingredients. Desserts are perfumed with aromatic cinnamon, cloves, and cardamom, floral orange and rose waters. Many Algerian sweets are pastry-based, often layered, with fillings, and meticulously decorated. Separate deserts are developed for occasions, for example, the mouna is served by newlywed women to other women during their traditional hammam. The tamina is a paste dessert with semolina, usually served to a woman after giving birth.