THE ESSENCE OF BRITISH CUISINE

The British cuisine relies on grains in breads, porridges, and puddings, with root vegetables like potatoes, carrots, turnips, and parsnips as everyday staples. Meat has long been central – beef, lamb, and pork usually cooked simply with salt, pepper, or a few herbs. Fish is equally important, from cod and haddock in fish and chips to smoked salmon and kippers. Dairy is everywhere, with butter, cream, and cheeses like Cheddar or Stilton used in both savory dishes and desserts. For sweets, sugar, dried fruits, and imported spices gave rise to classic British puddings, cakes, and pies.

British people maintain the usual three-meal pattern, though afternoon tea creates a unique fourth eating occasion, complete with sandwiches, scones, and cakes. Most meals feature tea as the beverage of choice, though beer is important, similarly to wine in France. Pubs and pub culture represent Britain’s social dining culture, where ale complements simple, well-prepared food.

GRAINS IN BRITISH CUISINE

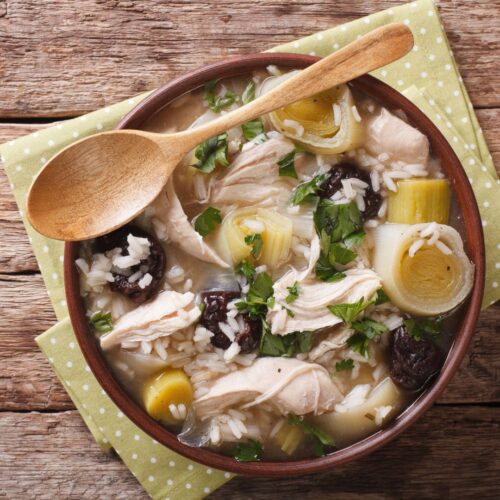

Wheat, oats, and barley dominate British cuisine. Oats are big in Scotland – morning porridge, sweet flapjacks for teatime, oatcakes that go with cheese. Barley’s mainly known for beer these days, though it used to be common in soups that filled people up cheaply. Wheat is mainly used for baking: crusty farmhouse loaves, soft buns, and the iconic British pies.

Pies are an absolute staple in British cuisine. Walk into any pub and you’ll see steak and kidney pie on the menu, that classic combination of tender beef and kidneys in rich gravy, all wrapped in buttery pastry. The Cornish pasty – it’s a complete meal wrapped in pastry, traditionally filled with beef, potato, swede, and onion. Miners used to carry these underground because the thick pastry crust acted like a lunchbox. Then there are the sweet pies – apple pie that’s served with custard, and treacle tart that’s sticky and wonderful. Pork pies are eaten cold, especially at picnics or with a pint, and they’re different from hot pies because they’re made with jellied stock that sets when it cools. The other type of pies, like Shepherd’s pie (made with lamb) or cottage pie (made with beef), are entirely different – they’re topped with mashed potatoes instead of pastry, but they’re still called pies because they follow that same principle of meat and gravy contained in something starchy. Fish pie shows up on family tables everywhere, usually made with white fish, prawns, and sometimes salmon, all swimming in a creamy sauce under a blanket of mashed potato.

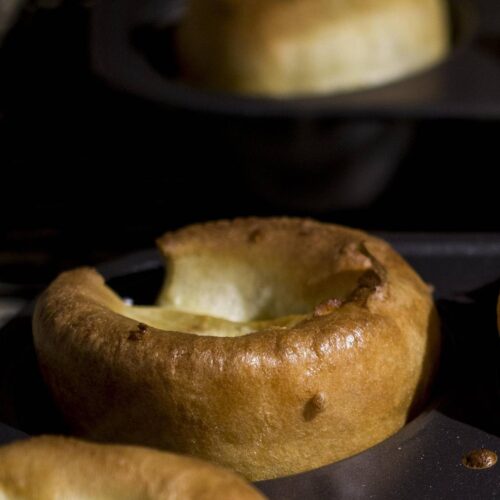

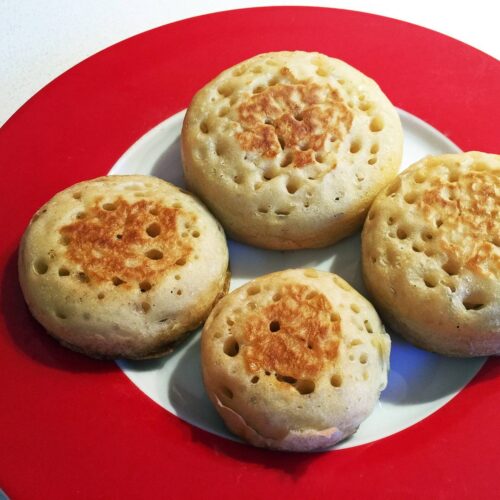

The British do something interesting with grains – they turn them into puddings all the time, and not only the grains, to be honest. British puddings are confusing because “pudding” means completely different things. They’ve got savory puddings like Yorkshire, which isn’t really a pudding at all – it’s batter made from flour, eggs, and milk that puffs up into crispy bowls perfect for holding gravy. Black pudding is actually blood sausage, not a pudding in any normal sense. Then there’s Christmas pudding, this dense, fruity creation soaked in brandy and traditionally set on fire when served. Spotted dick (yes, that’s really what it’s called) is a steamed pudding with currants served with custard. The British somehow decided ‘pudding’ was the perfect word for all these completely different things, and now it just means “dessert” half the time when people say ‘what’s for pudding?’

PRODUCE IN BRITISH CUISINE

These starchy roots are treated less as a side and more as a defining component of a meal. During wartime, potatoes became a state-promoted staple (‘Potatoes Are Good for You’ campaigns) and this love remained. The devotion is so strong that meals often feature multiple potato preparations on one plate – mashed potatoes and chips, or roasted potatoes and chips!

Northern Europe’s winters made country dependent on all types of long-lasting veggies – beets, carrots, rutabagas, parsnips, radishes, onions. Carrots gained popularity during wartime as sugar substitutes in cakes and desserts. Britain’s embrace of parsnips is quite distinctive – while most countries largely abandoned this root, the British love it in Sunday roasts or soups, like the warming parsnips and apples harvest soup.

British love preparing their root veggies with two-stage method: parboiling followed by high-heat roasting. This creates crispy exteriors and fluffy interiors that the British love. Honey glazing is another practice for root veggies, it involves adding honey to beets or parsnips only in the final 8-10 minutes of cooking to achieve caramelization without burning. Later often combined with thyme or sage.

Green peas, or mushy peas, are a British classic. Peas have been grown since Roman times, but mushy peas became a classic side in the mid-20th century. Their bright green color made them visually appealing, and soft texture complemented crispy fish. Today, mushy peas are both nostalgic and practical, still loved for their comfort-food appeal and mild sweetness without asserting strong individual character.

This English proverb shows how deeply apples are tied to health and folklore. The UK has over 2,000 apple varieties used in sweet and savory dishes: apple pie, apple Charlotte (a breadcrumb pudding with stewed apples), pork and apple sauce (a Sunday roast staple since medieval times), ploughman’s lunch (apple slices with cheese, bread, and pickles), and, of course, apple cider.

MEATS IN BRITISH CUISINE

Chicken is used in everything from roast dinners to curries and sandwiches. British consumers prefer versatile and economical meat options, therefore beef mince ranks as the most popular UK meat product, later transformed into beloved cottage pie (minced beef with creamy mash), savoury mince (versatile seasoned mince with veggies), or beef pasties.

The Sunday roasts traditions are Britain’s weekly meat celebration. Most families choose between lamb with mint sauce, roast beef with Yorkshire pudding and gravy, or pork with crackling and apple sauce. This tradition has endured as a family gathering ritual—one of the few times everyone sits down together for a proper meal.

For weekday comfort, bangers and mash is quintessentially British – sausages with mashed potatoes, served with onion gravy. The term ‘bangers’ supposedly comes from wartime sausages that would burst in the pan, though modern versions are of better quality. Surprisingly, Brits eat more sausages per capita than Germans, despite Germany’s reputation for sausage-making.

Another British institution is the full English breakfast, featuring bacon, eggs, sausages, black pudding, baked beans, grilled tomatoes, and mushrooms. During the Georgian and Victorian periods, the wealthy transformed breakfast into elaborate displays of hospitality featuring estate produce and fine tableware, which the emerging middle class eagerly copied. The tradition spread to all social classes during the Industrial Revolution, as factory workers needed big morning meals for physical labor, making the full English breakfast a dish enjoyed across British society for centuries. Still today, while hardly a health food, it serves as a weekend treat or hangover cure. Though not eaten daily, it remains central to British culture, especially in cafes and hotels.

Despite a tradition of eating red meat, Brits now eat less of it and more white meat. Productivity gains in pork and poultry sectors have reduced production costs, displacing some traditional beef and lamb from British plates.

FISH AND SEAFOOD IN BRITISH CUISINE

Overall, British preference is quite narrow – all other seafood falls into the remaining 20 percent, showing that Brits are quite conservative in their seafood choices despite having extensive coastlines. Cod is the fish of choice in the famous fish and chips dish, and haddock is the second most popular white fish and the most popular fish for smoking, commonly dyed bright yellow.

Kippers represent a fascinating case of decline and potential revival in British food culture. These smoked herrings were once an iconic British breakfast dish that peaked in popularity in the 1950s when fishermen caught over 100,000 tons of herring annually in the North Sea alone. However, overfishing devastated herring stocks, leading to a 10-year fishing ban that put many trawlers out of business, causing kipper consumption to plummet almost overnight. Today, their popularity remains quite low, with surveys showing that more than half of Brits don’t even know that a kipper is a fish.

EGGS AND DAIRY IN BRITISH CUISINE

A Scotch egg is a classic pub snack: a hard-boiled egg wrapped in seasoned sausage meat, coated in breadcrumbs, and deep-fried. Despite the name, it has nothing to do with Scotland. It’s so quintessentially British that it’s become a symbol of traditional pub food.

British pubs have a unique tradition of serving pickled eggs as bar snacks, often sitting in large jars behind the bar for months. These vinegary eggs are salty, and they do increase beer sales – a brilliant bit of British business psychology disguised as food.

Milk dominates British dairy consumption, particularly semi-skimmed milk. Cheese is Britain’s most popular dairy product, reaching 94% of UK adults’ refrigerators.

Britain’s cheese diversity is extraordinary – over 700 named British varieties exist. However, despite this impressive variety, British consumption remains moderate at 12.1 kilos per capita annually compared to other European countries.

During WWII, the government took control of milk production and forced everyone to make a standardized ‘Government Cheddar,’ nearly wiping out all other cheese varieties in Britain. This industrial approach lasted almost a decade after the war ended, meaning that new generations of Britons grew up without exposure to diverse cheese varieties, creating lasting conservative eating habits.

What makes cheddar truly unique is the ‘cheddaring’ process – after the curds form, they’re stacked into blocks and repeatedly turned and restacked to drain whey. This technique is where the cheese gets its name, yet most ‘cheddar’ sold worldwide isn’t actually made this way. Originally, to be called cheddar, cheese had to be made within 30 miles of Wells Cathedral in Somerset. Today, only one producer remains in the actual village of Cheddar, making them technically the sole ‘authentic’ cheddar makers left.

Back on the British preferences: red Leicester claims second place with 20% popularity, followed by mozzarella at 18%, then halloumi and brie tied at 15% each – traditional British cheeses hold their ground against international favourites.

DESSERTS AND NUTS IN BRITISH CUISINE

British desserts tend to be comforting and quite traditional. Classic puddings are huge in Britain, like sticky toffee pudding, bread and butter pudding, rice pudding, and spotted dick (a steamed pudding with currants). These are served warm with custard or cream. Steamed puddings have a special place in British hearts, particularly Christmas pudding, but also lighter versions served year-round. Trifle is another classic – layers of sponge, fruit, custard, and cream that’s perfect for gatherings.

Fruit-based desserts are very popular, especially crumbles (apple, rhubarb, or mixed berry with a buttery oat topping) and pies like treacle tart, Bakewell tart, and banoffee pie. Eton mess – a delightful chaos of strawberries, meringue, and cream – is another favorite.

British baking culture also embraces afternoon tea treats like scones with jam and clotted cream, Victoria sponge cake, and various tea cakes and biscuits.

What Brits really love is the combination of rich, warming flavors with creamy accompaniments. Almost everything comes with custard, cream, or both. There’s also a nostalgic element – many of these desserts evoke childhood memories and family traditions. The focus tends to be on comfort and satisfaction rather than elaborate presentation.

Nuts aren’t used extensively in traditional British cuisine compared to many other culinary traditions.