THE ESSENCE OF SOUTH KOREAN CUISINE

Korean cuisine is complex in a global context. First, there’s technical complexity. The wide, multi-stage fermentation varies by season, region, and household – each batch of kimchi (veggies) or doenjang (soybean paste) carries its own character. Second, meal structure. Korean meals don’t center on a single dish but unfold through banchan – small side dishes of pickled, fermented, sautéed, steamed, raw, and marinated components all at once. Diners can themselves compose each bite, adjusting salt, sour, sweet, heat, fat, and funk right at the table. Soups and stews are not considered banchan. This modularity is a hallmark of Korean dining. Third, the complexity of maintaining balance across the entire table – already a wider scope than most cuisines demand.

At the core of daily Korean meals are, of course, rice, a variety of banchan with spinach, bean sprouts, radish, seaweed, often seasoned with garlic, sesame oil, and soy. Fermented condiments, such as gochujang chili pepper and soybean paste, doenjang soybean paste, and ganjang soy sauce, provide distinctive depth and umami. Modest portions of meat, fish, tofu, or eggs round things out.

Korean cuisine stands out for balancing contrasts: spicy against mild, fermented against fresh, hot dishes alongside cold ones. It’s also a bold cuisine – the use of chilies since its introduction in the 16th century became a defining marker, setting it apart from older East Asian, Japanese, or Chinese traditions. Korean soy sauce is darker and richer than Japanese; food generally is heartier and flavored more.

Charcoal grilling and stone-pot cooking (e.g., dolsot bibimbap) are common, contrasting with China’s wok-centered stir-frying and Japan’s frequent raw or lightly handled seafood; grilling at the table is especially characteristic in Korea.

A normal pattern is to eat three meals a day: breakfast, lunch, and dinner. Breakfast is often early, either at home or a light breakfast at a company cafeteria on weekdays. Lunch is eaten out at company cafeterias or nearby restaurants, and dinner tends to be the largest and most relaxed meal of the day, often consumed at home.

GRAINS IN KOREAN CUISINE

In Korea, rice (bap) is a primary staple, a bowl of plain steamed white rice is inseparable from bap-guk-banchan (rice-soup-side dishes) meal structure. When people sit down to eat, the phrase for “have you eaten?” is basically “did you have rice”? Short-grain varieties are preferred for their sticky texture, not seasoned much – they stay neutral and balance bold flavors of other sides. In Korea, rice is rarely stir-fried or served alone – it’s always part of a table and takes on cultural symbolism (warm rice equals care and love).

In the past, there were over 1,500 varieties of traditional rice in Korea, but under Japanese colonial and modernization pressures, many were lost; only a fraction remains cultivated. White rice became widely accessible only in the late 20th century; for much of history, Koreans mixed rice with barley, millet, beans, or sorghum (boribap, japgokbap) to stretch rice.

Traditional rice was cooked in heavy cast-iron pots, leaving a toasted crust. Nurungji: the crispy, golden rice crust was sometimes turned into a snack or tea. This crust’s infusions become sungnyung, a roasted rice water sipped after meals to close dining – an old custom distinctively Korean among rice cultures. Sungnyung’s also has a palate-resetting effect after salty-spicy foods. Electric rice cookers reduced natural crust, prompting commercial nurungji.

In everyday meals, the default white rice is plain. But Korea also has a tradition of various mixed baps, here are a few interesting kinds:

- Japgokbap – “mixed-grain rice.” White rice cooked with barley, millet, sorghum, or corn. It was common historically when white rice was scarce.

- Kongbap – rice with black soybeans or green peas, giving extra protein and a nutty taste.

- Bambap – rice with chestnuts, popular in autumn.

- Patbap – rice with red beans, often made on dongji (winter solstice).

- Yakbap – sweet rice with jujubes, chestnuts, pine nuts, honey, and soy sauce, traditionally made for festive occasions.

- Dolsotbap – rice cooked in a hot stone pot, which naturally creates a layer of nurungji at the bottom. Hot water is then poured in to make sungnyung.

- Namulbap – rice cooked or served with seasoned wild greens. This is a spring tradition tied to foraging.

- Bibimbap – the most famous: rice mixed at the table with assorted vegetables, egg, chili paste, and sometimes meat.

Noodles are definitely loved in Korea, but they don’t have the same cultural weight as in China or Japan. In China, noodles are one of the two great pillars alongside rice; in Japan, soba, ramen, and udon each have strong traditions and dedicated rituals. In Korea, rice is still the unquestioned centerpiece, and noodles are more of a complementary, yet of great variety. Noodle dishes are called guksu.

In Korean noodle families, rice noodles appear far less frequently than in Southeast Asia. Historical scarcity of rice favored buckwheat and later wheat in noodle-making, and the sweet potato starch provided glass noodles for japchae. Noodles are served as hot soups, cold broth, or mixed or stir-fried, which can also be either hot or room temperature. When deciding what to order, you may think like that:

- Want hot, soothing soup and soft chew: kalguksu, anchovy–kelp–seafood broth; flat noodles.

- Want hot, clear, gentle broth without spice: onmyeon/guksu jangguk, beef-based clear broth; wheat somyeon.

- Want cold, clean tang and resilient chew: mul naengmyeon (Pyongyang style), cold buckwheat noodles in icy broth.

- Prefer spicy cold mix with easier bite: bibim guksu, with very thin wheat noodles called somyeon.

- Prefer spicy cold mix with maximal chew: bibim naengmyeon (Hamhung style).

- Want a stir-fry centerpiece or banchan: pick japchae, stir-fried sweet potato glass noodles.

- Crave robust, spicy seafood heat: jjamppong.

- Crave savory-sweet black bean comfort: jjajangmyeon, wheat noodles adapted from Chinese cuisine.

Wheat, corn, and barley stepped in when rice was scarce, and they’re pretty big now. Barley was the most common substitute for rice and even now many households serve rice mixed with barley. Barley tea (bori-cha) it’s the default water in many homes and restaurants.

Korea’s climate didn’t favor large-scale wheat until more recent times; wheat flour was more of a specialty. Still, it became central in knife-cut noodles or cold buckwheat noodles often blended with wheat. During the 1950s–60s, when rice shortages were severe, the government even promoted “flour food days,” wheat noodles, steamed buns, and dumplings. That policy left a legacy: noodle shops and wheat-based snacks grew in popularity.

Corn was more common in northern regions. People boiled or roasted corn as a snack, ground it into flour for porridge (oksusu juk), and mixed it with rice to stretch meals. Like barley, corn tea (oksusu-cha) is also common.

PRODUCE IN SOUTH KOREAN CUISINE

There’s a live misconception that Korean food is low on vegetables, limited to kimchi as a side, and unfriendly to vegetarians. Quite the opposite. For long, Korea was not a wealthy society; most meals were plant-centered, with meat as added only for special occasions. Even now, If you eat in a home-style setting, vegetable dominate the banchan: spinach, bean sprouts, cucumbers, radishes, greens. Stews often include tofu and mushrooms. The meat-centric BBQ culture that many foreigners know is more of a dining-out experience than everyday food.

The iconic Korean kimchi began as salted vegetables. People wanted veggies to last throughout winters, and this wasn’t unique to Korea; China also had fermented vegetables. The crucial turning point was American chili peppers, which Koreans adopted into their ferments with great speed. By the 18th century, the bright red, spicy napa cabbage kimchi had become standard. Koreans also layer garlic, ginger, scallions, chili, and fish sauce to produce deeply punchy flavor.

Every Korean manages to consume a respectable 36-40 kg (1,270-1,410 oz) of kimchi per person yearly; yet its consumption has declined over the past two decades. Lifestyle shifts, Westernization, dining-out, breakfast skipping, concerns about sodium – all trends pronounced among younger adults caused this.

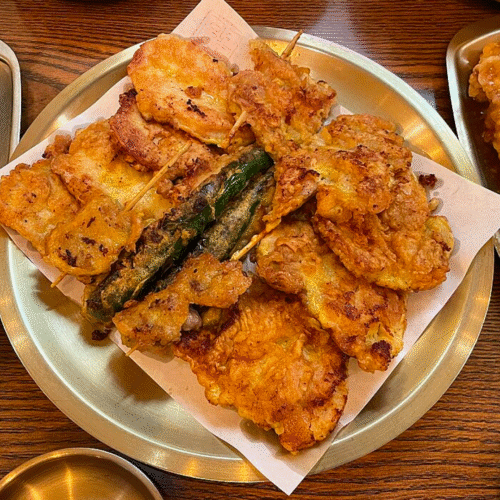

A proper Korean meal includes namul (lighly seasoned greens, dressed with sesame oil, garlic, soy sauce, chili flakes), braised roots, pickled radishes, and more. Other popular veggie dishes are jeon (savory pancakes of zucchini, scallions and kimchi), japchae (sweet potato noodles tossed with lots of vegetables – carrots, spinach, onions, bell peppers, mushrooms).

Ssam is a very Korean way to use raw greens as an edible wrapper. At BBQ, you wrap meat, but even without meat, rice and condiments tucked into lettuce, perilla leaves, or cabbage make a meal.

Koreans have long relied on legumes, especially soybeans. They’re made into tofu, sprouted for the popular side dish kongnamul (soybean sprout dish), or ground into soy milk that becomes the base of refreshing kongguksu noodles. They’re also at the heart of Korea’s famous fermented condiments doenjang, ganjang, and gochujang, used for so many dishes.

Mung beans (small, green Asian legumes) are popular in bindaetteok (mung bean pancake) or mild jellies made from mung bean starch, nokdumuk. Azuki beans (small, reddish-brown legumes) carry both comfort and tradition. They’re used in sweet rice cakes, breads, and the warming winter porridge patjuk, once believed to ward off evil spirits.

Surrounded by ocean on three sides, the Korean peninsula has long relied on the sea not just for fish, but also for edible algae and seaweeds:

- Gim – thin sheets of roasted, seasoned seaweed, eaten as a snack or used to wrap rice. This is the Korean equivalent of Japanese nori, but more seasoned with sesame oil and salt for a richer taste.

- Miyeok is a type of wakame seaweed, mostly used in miyeok-guk seaweed soup. This dish is eaten by women after childbirth for recovery, and by everyone on birthdays as a symbol of health and longevity.

- Dasima – kelp, simmered to make a broth, is an umami base to Korean cooking.

Asian pears, persimmons, apples, citrus, melons, and berries are popular in South Korea. Asian pears and persimmons were especially important, as gifts, in ceremonies, in traditional medicine, as meat marinades, and all over art and poetry.

MEAT IN KOREAN CUISINE

Koreans were a farming society; rice and grains were the backbone of meals, and meat was more of an addition. Buddhism, which was influential in Korea for centuries, encouraged vegetarianism and even outright bans on slaughtering animals. This made meat less important in everyday cooking. Beef has long held special to Confucian rituals, it carried symbolic weight. Serving beef was a way of honoring family and maintaining social order.

Pork became really popular after the Korean War (1950–1953). It was cheaper, and in South Korea’s rapidly developing economy, pork really took off. For centuries, chicken was often cooked in soups or stews, valued for nourishment and believed to restore strength. Chicken gained much bigger popularity in the late 20th century, with urbanization and the rise of casual dining, fried chicken became a national phenomenon. Today, Korean fried chicken (crispy, twice-fried, often with sweet or spicy sauces) is one of the most famous food exports. It pairs with beer in the beloved “chimaek” culture: chicken + maekju/beer.

You’ll notice that Korean meat dishes almost never present large steaks or roasts. Instead, meat is cut into thin slices, bite-sized pieces, or ground. In earlier times, meat was scarce and expensive, so cooks stretched it by mixing it with vegetables, rice, or noodles. Cutting it small also makes it easier to marinate, grill, and share at the table. You also won’t find knives on a Korean table. The cutting is done in the kitchen, and food is served ready to eat with chopsticks and spoons.

Korean barbecue we know today grew out of much older grilling traditions but really took shape in the 20th century. Dishes like bulgogi (thinly sliced, marinated beef) go back to the Goguryeo kingdom (over 1,000 years ago). However, grilling wasn’t a common daily meal. In the 1970s and 1980s, with urbanization and rising incomes, restaurants began specializing in table-top grilling. This was the birth of what people now call “Korean BBQ” culture. It’s hugely popular in South Korea, especially with samgyeopsal – grilled pork belly. As a global phenomenon, Korean barbecue restaurants are thriving in the U.S., Europe, and across Asia. Gui in Korean cuisine simply means “grilled dish.” It’s not one single food but a whole category of cooking meat, fish, or vegetables at the dining table.

Are Koreans heavy meat eaters today? Compared to the past, absolutely more than before. Modern Korea has one of the highest per-capita pork consumption rates in the world, and barbecue culture is central to dining out. Yet meat is still paired with plenty of vegetables, rice, and sides — so the meal feels varied rather than dominated by meat.

FISH AND SEAFOOD IN SOUTH KOREAN CUISINE

Each Korean coastline has something to brag about – oysters from the south, crabs and clams from the west, sea cucumbers and abalone from Jeju. Seafood also has a whole ecosystem in Korean cuisine.

It all starts with what most people never see: anchovy-kelp stock. Nearly every soup, stew, and noodle bowl begins with dried anchovies and kelp simmered together, sometimes with radish or mushrooms. The result is clean, briny, and fast stock, that builds a marine depth into daily cooking.

Then there’s the raw side. Koreans eat raw fish quite often, but also differently from Japanese sashimi. Hoe is Korea’s version of raw seafood; it ranges from simple slices of fish to the infamous sannakji. Hoe is sliced thick, eaten with gochujang. Sannakji – tiny octopus pieces that arrive slicked with sesame oil. Its suction cups are still gripping, a visceral expression of freshness.

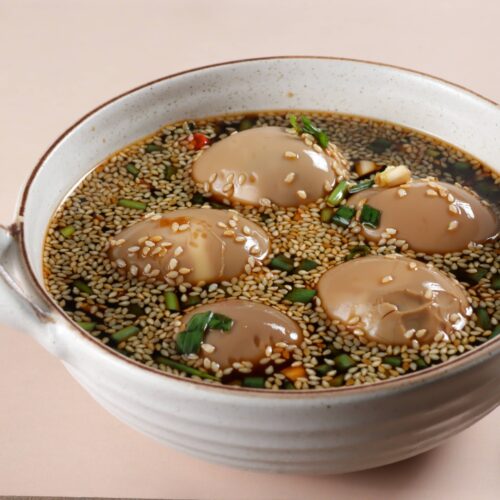

Small in portion but huge in impact, also very important to Korean flavor identity is jeotgal, a category of salted, fermented seafood. Tiny shrimp, anchovies, oysters, roe, or crab are preserved into condiments that power kimchi, appear as punchy side dishes, or become fish sauces aekjeot. They’re small in portion but huge in impact, very important to Korean flavor identity.

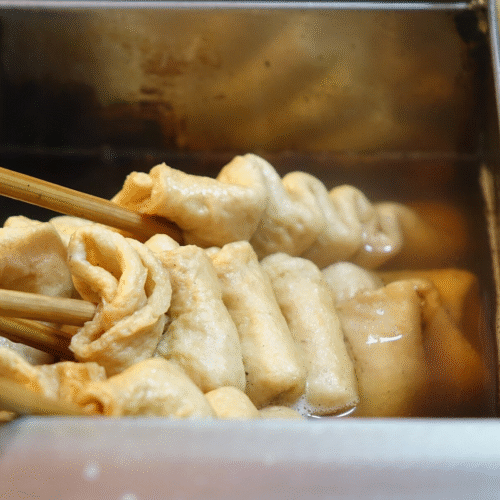

Fish and seafood are eaten daily – grilled fish on open flames, skewered squid, dried cuttlefish, and fishcakes (eomuk/odeng) served with hot broth, it’s an everyday snack and street food. Koreans are the world’s heaviest eaters, averaging around 55 kilos (1,940 oz) per person each year.

EGGS AND DAIRY IN SOUTH KOREAN CUISINE

Eggs are very common in Korean cuisine. You’ll see them in gyeran-jjim (savory steamed egg custard), fried eggs topping bibimbap or noodles, and rolled omelets gyeran-mari packed in lunchboxes.

Milk and dairy, on the other hand, are not traditional. Korea didn’t have a dairy culture; most Koreans are lactose intolerant, so milk, cheese, and butter were absent for a long. That changed a bit after the Korean War, when U.S. aid introduced powdered milk and school milk programs. Today, yogurt drinks and cheese are present, but only as a modern Western influence.

NUTS, OILS, AND DESSERTS IN SOUTH KOREAN CUISINE

Nuts do appear, but as a garnish, snack, not an everyday ingredient, but sesame and sesame oil are big. It’s actually the signature Korean oil – aromatic, nutty, used more as a seasoning over bibimbap, japchae, namul vegetables, or any other dish. South Koreans use moderate amounts of neutral oils for frying. When used, they’re soybean and canola at home, and palm oil is widespread in foodservice for cost reasons. Flavors are built with finishing oils, like the aforementioned sesame and perilla.

Korean desserts are subtle and light, made of rice, beans, grains, nuts, honey, and fruits. The sweetness is delicate, just enough to balance bitterness. Chewy texture is very preferred, also crunchiness, or soft pressed sweets that dissolve on the tongue. Visually, many are shaped with molds, decorated with patterns, or colored naturally with plants. Tea-culture roots and ritual/seasonal usage keep portions small.

Hangwa is the umbrella for traditional confections made from grain flours bound with honey, yeot (rice/malt syrups), or sugar, then steamed or fried and coated with seeds, puffed grains, or nuts. Signature types include yakgwa (fried wheat dough soaked in honey syrup), gangjeong/yugwa (puffed or fried rice sweets coated in syrups and seeds), jeonggwa (candied fruits/roots), and dasik (pressed tea cookies using powders like sesame, chestnut, or bean).

Another is tteok (rice cakes) category, which uses glutinous or non-glutinous rice flours to create chewy or tender textures; sweet forms include songpyeon, injeolmi, baekseolgi, and yaksik (glutinous rice with jujube, chestnut, pine nuts, honey/soy).

A few Korean desserts have spread worldwide recently, like bingsu, the shaved ice dessert topped with fruit, condensed milk, or sweet red beans. Also, dalgona, the caramelized sugar candy, went global after the Netflix series Squid Game (2021).