THE ESSENCE OF MOROCCAN CUISINE

Moroccan cuisine is often considered complex due to its extensive layering of flavours, sweet-savory combinations, and intricate cooking methods, which involve slow cooking and careful balancing of spices and ingredients. Cuisine is also wide with regional variations of the same dish across country.

On the other hand, the essence of Moroccan cooking lies in the simplicity of its base ingredients — grains, vegetables, and meats. Many traditional recipes are passed down through generations.

Moroccan diet is mostly grain-oriented compared to its Mediterranean neighbors, with high wheat, barley, and maize consumption. Primary plant proteins are fava beans, lentils, and chickpeas; animal proteins are goat, mutton, lamb, chicken, pigeon, beef, and fish in coasts. Milk is found in custards and cheeses, yet it is rarely consumed fresh or as yogurt. Characteristic are lemon pickles, argan oil, cold-pressed, unrefined olive oil, and dried fruits. The use of spice is absolutely crucial.

For breakfast, many Moroccans enjoy a light meal of bread, cheese, olives, honey, split fava beans dip bissara, spongey semolina pancakes baghrir, and sweet mint tea. Lunch, the day’s largest meal, may include soup, raw or cooked salads, tagine, couscous topped with meat, vegetables, fresh or dried fruit. Dinner is a smaller, less important meal than lunch — unless guests have been invited, in which case locals organize a lavish feast. Upon entering home, guests are offered food and tea within seconds. In Moroccan culture, mint tea is a symbol of hospitality, tradition, and social bonding, sometimes called “Moroccan whiskey” for its importance.

Moroccans usually share food in a communal style while sitting on the floor; however, here, this communal way of eating is not called meze, which is more associated with Eastern Mediterranean and Middle Eastern cuisines. Food is scooped from a shared bowl using only the right hand, and leftover juices are soaked out with bread. Moroccans usually eat at home; should they eat out, most locals would eat street food rather than go to restaurants.

GRAINS IN MOROCCAN CUISINE

Cereals are an inexpensive, accessible, security-providing food base for all income levels. Wheat is the most crucial – the average per capita consumption is almost 500 grams daily, three times the global average (156 grams). Wheat is used for breads: classic khobz, yeasted oven-baked rounds, rghifa or mssemen, a griddle-cooked flatbread, and harcha, a small, circular semolina bread. Harcha is excellent for making small sandwiches with honey, butter, or jben arabi, a fresh cheese. Wheat also features baghrir pancakes, very popular in North Africa’s streets. The ancient recipe was created by the Berbers in Tamazight, one of the Berber languages, a word that translates to “too soft”.

An essential wheat product is warqa pastry, resembling Eastern Mediterranean phyllo, made from leaf-thin dough, stretched out into sheets, making it great for layered crispy dishes like pastilla (meat or seafood pies).

Couscous grains are made from steamed balls of semolina – the hardest part of durum wheat, which resists grinding. Semolina is hand-rolled from small pellets, sprinkled with dry flour to keep them separate, and then sieved. Any pellets that are too small to be finished, granules of couscous fall through the sieve and are again rolled and sprinkled with dry semolina and rolled into pellets. This labor-intensive process continues until all the semolina has been formed into tiny granules. In modern times, couscous production is largely mechanized. Its further preparation is also not as simple as grains are steamed several times to achieve a fluffy, light texture.

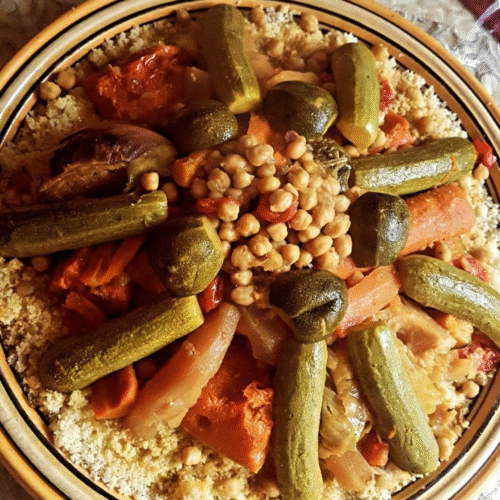

While the base grain is simple, couscous dishes vary: served with lamb, chicken, fish and are accompanied by a medley of vegetables and endless combinations of spices. Usuallty couscous is eaten on Fridays, the Muslim holy day, when families gather after prayers. Reflecting its cultural importance, couscous has been recognized by UNESCO as an Intangible Cultural Heritage.

PRODUCE IN MOROCCAN CUISINE

Vegetables are essential, though quantities consumed are comparatively low. Due to economic disparities, some struggle with the affordability of certain foods, including fresh vegetables. Unlike the raw vegetable salads familiar in many Western cuisines, cooked salads are popular in Morocco. They feature eggplants, tomatoes, peppers, and carrots, often roasted or stewed and then served at room temperature or chilled. Vegetable pickles from carrots, cucumbers, turnips, cauliflower, and green beans are common.

Bright, impossible to miss, bell peppers are a Moroccan staple. They can be roasted or grilled for both warm and cold salad dishes, diced and cooked with fish, or blended into harissa to balance out the heat of chilli peppers. Moroccan salads are usually flavored with lemon, garlic, olive oil, cumin, paprika, and cinnamon.

Fruit choice is wide, from local Mediterranean natives to tropical ones. Main meals are concluded with fresh fruits and assorted nuts: platters of fresh oranges, figs, dates, and melons, sometimes sprinkled with cinnamon. When fresh fruits are out of season, dried fruits take their place.

In meat dishes, they lend a sweet contrast to savouriness and spiciness and the contrast in texture. Fruit sauces and purees from figs, apricots, and plums accompany lamb and poultry.

Preserved lemons, or leems, are a crucial condiment to tagines. Diced, quartered, halved, or whole lemons are pickled in a brine of water, lemon juice, and salt. The pickle can ferment at room temperature for weeks or months before use. The pulp of the preserved lemon can be used in stews and sauces, but it’s the peel that is most valued. The flavor is mildly tart and intensely lemony.

MEATS IN MOROCCAN CUISINE

Lamb is especially priced meat during the Eid Al Adha Muslim holiday, which Moroccans celebrate by sacrificing sheep. During this much-anticipated day, it is not uncommon to see sheep strapped on people’s backs, waiting in stairways of apartment buildings, stuffed into car trunks, or even riding on motorcycles! After holy rituals, every single part of the animal is saved and eaten. The liver is eaten first, as it is more perishable than other parts. The intestines and other small bits are hung outside to dry for days in the sun and are used later for flavoring.

Other than the usual meats, game, snails, pigeons, and camels are quite popular.

Perhaps the most unusual Moroccan dish you’ll come across is pastilla – also known as bastilla, or bisteeya. Chicken, pigeon or seafood is cooked with onions and spices, then shredded and mixed with eggs. And then things get interesting: almonds are crushed, sugar and cinnamon are added to almonds, and then both mixtures are layered in a crust. The pie is baked, and then more sugar and cinnamon are sprinkled on top. The result is sweet, savory, delicious and unusual.

One of the most iconic Moroccan dishes, a tagine, refers both to the conical clay cooking vessel and the stew cooked in it. Lamb, beef, or chicken are slow-cooked with a medley of spices, dried fruits, vegetables. The slow cooking process in the tagine’s unique shape allows meat to become exceptionally tender.

Morocco stands out for its sophisticated approach to organ meats, particularly met in street food culture. Moroccans have many offal dishes, like couch (grilled liver skewers), boulfaf, where lamb liver is carefully wrapped in caul fat before grilling; tkalia, a complex stew incorporating multiple organs like tripe, lung, and heart – Moroccans create depth of flavour from these ingredients.

FISH AND SEAFOOD IN MOROCCAN CUISINE

Fish and seafood are hugely popular along coastline but way less inland. Fish come in tagines, pastillas, and are grilled whole, baked, or poached, in combination with tomatoes, bell peppers, onions, dried fruits, nuts, and chermoula sauce – all a distinctive North African footprint.

EGGS AND DAIRY IN MOROCCAN CUISINE

Egg dishes are pretty frequent, from tomato-based shakshuka to hard-boiled eggs flavored with cumin as a street snack or saffron-tinted eggs for tagine garnishing. Shakshouka is a North African staple dish, the origin of which is still being determined, with claims of Moroccan, Tunisian, Turkish, and Yemeni origin. Moroccan shakshouka is typically spiced with cumin, paprika, harissa, preserved lemon, and olives and sometimes includes lamb or merguez sausage.

Milk and dairy are not central in Moroccan cuisine – fresh milk is rarely consumed. Leben, a fermented milk drink similar to buttermilk, is preferred. Raib is homemade fresh yogurt, creamy and smooth, enjoyed as a dessert or a snack. While not as central as in some other cuisines, fresh cheese jben arabi is common, served with bread and olives.

A distinctive ingredient of North African cuisine is smen – a salted, fermented butter, similar to ghee and niter kibbeh (Ethiopian clarified butter), but has a characteristically strong, rancid, and cheesy taste and smell. Smen can be fermented for over 20 years, perhaps even more: Berber farmers in southern Morocco will sometimes bury a sealed vessel of smen on the day of a daughter’s birth, aging it until it is unearthed and used to season the food at the daughter’s wedding. However, its pungent and distinctive flavour means you either love it or hate it.

NUTS AND DESSERTS IN MOROCCAN CUISINE

This heightened level of sweetness comes from the generous use of honey, sugar, and sweet fruits. It is balanced by nuts, floral waters (orange blossom, rose petals water), cinnamon and saffron.

Nuts are a key in many desserts. Almonds, pistachios, and walnuts fill traditional pastries. Ground nuts are used in dips and spreads, for example, amlou, a Moroccan dip made with almonds, argan oil, and honey, and served with bread. Almonds and pine nuts are added to tagines and couscouses for texture and flavor, sprinkled on salad for a crunchy contrast.