THE ESSENCE OF LITHUANIAN CUISINE

Lithuanian cuisine stands out for its quiet honesty. It’s food built around the land, the seasons, and simplicity. It doesn’t try to impress through spice or showy technique, but focuses on a few humble ingredients prepared with care. Potatoes, rye, dairy, pork, mushrooms, beets, and cabbage form its foundation. The cuisine draws heavily from a brief growing season. Root vegetables, mushrooms, and berries appear regularly boiled, pickled, or fermented. Rye bread is very traditional. Dairy is big: sauces, soups, pancake batters, and as an accompaniment.

Lithuanian dishes favor harmony over contrast. They’re meant to comfort and satisfy, not to jolt the palate with acidity or heat. Cepelinai, kugelis, potato pancakes are hearty and smooth, served with sour cream, crisp bacon, or creamy sauces. Those additions deepen richness and warm satisfaction, rather than cut it.

Lithuanian cooking values texture and mild layering of flavors: the softness of potatoes, the saltiness of pork, the creaminess of dairy. Seasoning is minimal: salt, pepper, dill, caraway, a little onion or garlic.

Lithuania doesn’t have a strong dining-out or street culture in the way many other countries do. It is actually distinctive by its home-centeredness. For most Lithuanians, a proper meal is something warm and freshly prepared. Even younger generations, who might grab coffee or fast food, often return home for real soup, potatoes, roast. For centuries, Lithuania was a rural society where cooking at home wasn’t a choice. Under Soviet rule, eating out was rare, and options were limited. Restaurants weren’t a daily thing, so the culture of reliance on home cooking never disappeared.

GRAINS IN LITHUANIAN CUISINE

Long before potatoes arrived, grains were practical and perfectly suited to the climate. Rye was the most traditional, so rye bread (ruginė duona) is very much Lithuanian – it’s dense, slightly sour, and made with natural sourdough. Every household once kept its own bread starter for a weekly bread bake. Most Lithuanians eat it every day with soups, herring, or cold cuts and consider a meal incomplete without the bread.

Rye sustained everyone, and wheat was historically reserved for the wealthy, yet it is now Lithuania’s main cereal crop. Most of the wheat grown is winter wheat, suited to the local climate. Today, it supplies the flour for most baked goods, pasta, and pastries found in Lithuanian kitchens.

To mention a few iconic Lithuanian cuisines, kepta duona is one of Lithuania’s most recognizable pub snacks. Bread is sliced into sticks, fried, seasoned with garlic and salt, and served with a creamy cheese or mayonnaise-cheese dipping sauce. It’s humble and rustic, but irresistible.

Pancakes (blynai) are a staple breakfast or weekend brunch for most local families. Lithuanians make many kinds of curd pancakes (varškėčiai), yeast-raised pancakes (mieliniai blynai), and plain flour pancakes similar to crepes (lietiniai blynai), which may come with curd, meat, ham, and cheese stuffings. Pancakes are often paired with sour cream, jam, honey, or fresh berries.

Barley, oats, buckwheat, and millet were important too. Barley went into porridge and beer; oats in breakfast porridges and soups. Buckwheat (grikiai), in particular, has seen a resurgence for its health benefits; it’s eaten as a side dish or even as a replacement for rice. Buckwheat porridge flavored with butter, still today, is a daily breakfast in many families.

PRODUCE IN LITHUANIAN CUISINE

Potatoes define Lithuanian cuisine. No other ingredient shows up as often or matters as much. They arrived in the late 17th century but didn’t take hold until the 1800s, when they pushed out turnips and millet. Still today, Lithuania built its entire repertoire around them. The same ingredient becomes soft, crisp, creamy, or dense depending on how it’s handled. National dishes are all potato-based:

- Cepelinai – stuffed potato dumplings, the country’s signature dish

- Kugelis – baked potato pudding with eggs, onions, and bacon

- Vėdarai – potato sausage in pork casing

- Bulviniai blynai – potato pancakes with sour cream or bacon

Traditional produce reflects the country’s short growing season, unlike in southern cuisines, vegetables in Lithuania play a supporting role for meats, grains, or potatoes.

Spring means fresh greens, radishes, spring onions, sorrel, collected directly from a garden, put together to make a light spring salad, dressed with sour cream and dill. Summer is the peak of freshness: cucumbers, tomatoes, and new potatoes fill local markets. As autumn arrives, the emphasis shifts to storing carrots, beets, onions, and cabbage for pickling, fermentation, or cellar storage through winter.

I bet there are zero Lithuanians who don’t enjoy this iconic summer cold beet soup šaltibarščiai, of an impressive bright pink, almost neon purple color. Grated pickled beets and fermented milk kefir are combined to make an extremely bright, fresh, crunchy soup that also features fresh cucumbers, dill, spring onions, and hard-boiled eggs. Always served chilled with hot boiled potatoes as a contrast. A true must-try.

Wild mushroom picking is a competitive seasonal hobby. Lithuania stands out for its forest-to-table mushroom culture, and many families treat foraging as a seasonal tradition.

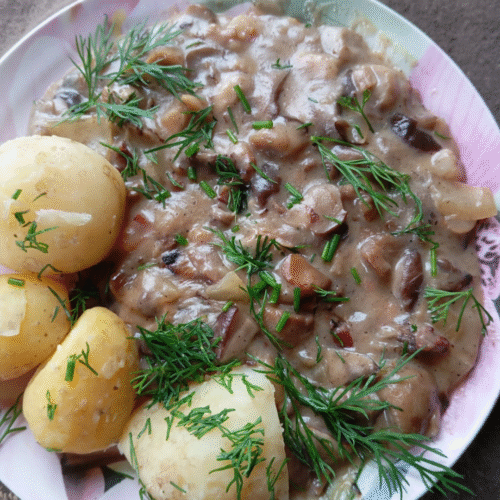

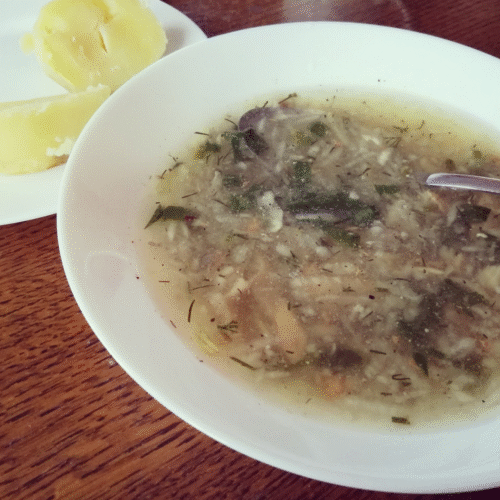

Lithuanians lightly fry chanterelles (voveraitės) with onions and cream, or add them to sauces for meat and potato dishes. Porcini (baravykai) and boletes feature soups, sauces, fillings for dumplings for Christmas Eve (Kūčios). When the meal is meatless, mushrooms stand in their place. Mushrooms are also dried, salted, or pickled to last till the next season, but the ultimate Lithuanian delight is the fresh-picked porcini, sauteed with butter and bacon.

Pulses have some traditional presence in local cuisine, but not an important one. Historically, peas and broad beans were the main ones, especially before potatoes became widespread. They were eaten boiled, mashed, or mixed with grains during fasting periods and by poorer households. Lentils, chickpeas, and other pulses are modern additions.

They’re everywhere: in gardens, markets, and kitchens. Apples are eaten fresh, baked, stewed, or turned into compotes — lightly sweetened drinks made from boiled fruit, a common everyday refreshment. In autumn, families store crates of apples in cellars to last the winter. They’re also central to simple home desserts like apple pie (obuolių pyragas), pancakes with grated apple, and baked apples with honey or cottage cheese. Even now, when supermarkets offer bananas and citrus year-round, apples remain the default choice.

Beyond apples, Lithuanian cuisine includes plenty of seasonal berries and stone fruits: strawberries, raspberries, currants, cherries, plums, cranberries, and lingonberries. What’s distinctive in a global context is how extensively Lithuanian home cooks turn all the produce into jams, compotes, and pickles for winter.

MEAT IN LITHUANIAN CUISINE

Lithuanians are serious meat eaters. Historically, meat was appreciated and too expensive for a daily diet, but as farming expanded and production rose during the 20th century, it became a regular part of everyday meals. Pork is by far the most common, symbolic, versatile and affordable meat, to the extent that Lithuania as a top 6 pork consumer per capita globally. You find it in sausages (dešros), meatballs (kotletai), schnitzel-like cutlets karbonadai, pork ribs with a diminutive name šonkauliukai, and bacon toppings (spirgai) used to flavor potato dishes. Back in the day, families would slaughter pigs, make some sausages or blood pudding, and smoke the rest for the winter. This preservation practice: smoked hams, sausages, and lard are very present today in local and commercial markets.

A taste of Lithuanian summer is definitely šašlykai – local take on grilled meat skewers or kebabs. Šašlykai are originally from Caucasus and Central Asia, they spread through the Russian Empire and later the Soviet Union as picnic food. Lithuanians adopted the dish in the 20th century and, over time, made šašlykai their own. To make it, large meat cubes are marinated with lots of onions, salt, pepper, and some acidic element – vinegar, kefir, mayonnaise – depending of family tradition. Then meat is skewered and grilled, served with fresh cucumbers, tomatoes, spring onions, and tomato sauce.

Beef appears less often, as cattle were more valuable for milk and farm work. When used, it was added to soups, stews, or boiled, served with horseradish and rye bread. In modern times, beef has become more common, but it still carries a sense of occasion. Beef tongue has a respected place on Lithuanian festive tables. The tongue is boiled slowly until tender, then sliced thin and served cold with horseradish or mayonnaise. In Soviet times, this was a classic cold starter at weddings or Christmas.

Chicken and duck are well integrated into modern Lithuanian cooking. Chicken is used in soups, schnitzel-like cutlets, and whole roast chicken for a family Sunday lunch. Duck, on the other hand, is a festive meat roasted with apples or served with berry sauces at Christmas.

Venison, wild boar, and hare were once status symbols on the noble table. Today, game remains seasonal and regional, often featured in restaurants or prepared by hunters. Its earthy flavor is paired with berries or mushrooms.

FISH AND SEAFOOD IN LITHUANIAN CUISINE

Fish is somewhat secondary, surely not a daily meal in Lithuania. Historically, fish were more common among coastal and inland fisher communities. Peasants ate it primarily during religious fasts — especially Lent and Christmas Eve (Kūčios). This ritual connection endures today — the Christmas Eve table is unthinkable without herring, pike, or carp.

Overall, freshwater fish – pike, perch, bream, carp, and eel dominate. Along the Baltic coast, you’ll also find plenty of sprats, herring, and cod. Herring and smoked dishes deserve a special mention; it’s deeply symbolic here: salted, pickled, layered into salads with beets, eggs, and mayo. You’ll spot it on holiday tables and weeknight dinners alike, often paired with hot boiled potatoes. Lithuania’s herring culture is a beautiful mix of Jewish, Nordic, and German influences — though the Jewish and Nordic roots run deepest.

Smoked fish, especially eel, perch, catfish, and mackerel, are kind of a specialty that has gone quite popular. Again, it’s not an everyday food, but during the local fairs, or in coastal cities, there will always be at least a few smoked fish stalls that locals would gladly go for.

True marine seafood is nonexistent traditionally, but imported shrimp, mussels, octopus are getting popular in modern dining. The only local, traditional ‘seafood’ is actually lake and river crayfish. In summer, they are caught and served boiled with dill as a delicacy.

MILK AND DAIRY IN LITHUANIAN CUISINE

Dairy. Mark it as a rich, tangy, creamy staples category – as important as meat or potatoes. Because the northern climate supports dairy farming well, and because the meat was pricey and appreciated, milk was base of nutrition for a long time, it created a tradition that lasts. For long, fresh dairy and curd cheeses dominated – all easy to produce in small farms, with minimal aging needed, intended for local consumption. The shift to more fermented or aging-type cheeses appears commercially only in the late 19th century.

Milk, kefir, and buttermilk are everyday items. For example, kefir, a thick, sour fermented milk drink, or buttermilk accompany boiled potatoes. Lithuanian butter and cream are described as ‘unusually rich’ in many sources. Sour cream is very prominent. It’s most likely sitting in all fridges in Lithuania to accompany soups, salads, dumplings, potato dishes, and even herring.

Curd cheese / white cheese (varškė, baltas sūris) is fresh curd and white cheese, flavored with caraway and served with fresh honey. The white curd cheese ‘Lietuviškas varškės sūris’ is protected under EU PGI status.

Once wandering in a local grocery shop, definitely grab some sweet curd cheese bars, called sūrelis. They’re made from silky sweetened curd cheese, flavored with vanilla, cocoa, or jams, and dipped in a thin chocolate glaze. They go either as a snack or a more nutritious dessert bar.

DESSERTS IN LITHUANIAN CUISINE

Many Lithuanian desserts lean on local staples: apples, poppy seeds, curd cheese, forest berries, and honey. They also lean towards flour dominant sweets – pies, bakes, biscuits, doughnuts.

On the simple side, you have things like the no-bake dessert tinginys, ‘lazy cake’, made with biscuits and cocoa. On the elaborate side, you have the iconic cake šakotis (tree cake) made for weddings – baked in layers over a rotating spit.

Šimtalapis (meaning ‘hundred-leave cake’) is one of Lithuania’s most elaborate desserts of Tartar minority origin, which has established deeply in Lithuania. It’s a complex to make, contains many thin layers of buttery dough, filled with poppy seeds, butter, and sugar, sometimes with raisins. Each layer is brushed with butter before baking, giving it a laminated texture similar to a croissant but denser and sweeter.

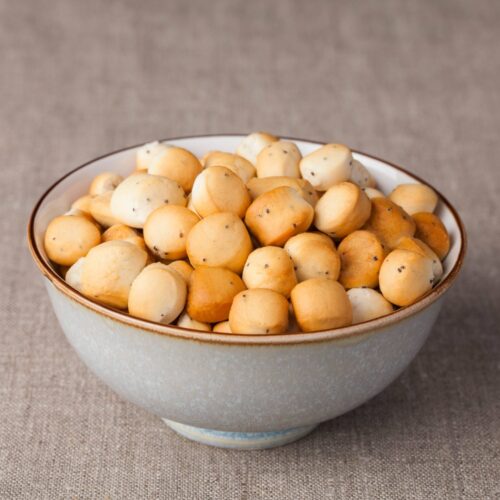

Uniquely Lithuanian are kūčiukai – tiny baked dough pieces, made from wheat flour, poppy seeds, yeast, sugar, butter, and milk. Once baked, they become crisp on the outside and slightly chewy inside. During Christmas Eve (Kūčios) dinner, they’re soaked in poppy milk – a mildly sweet, nutty liquid. Kūčiukai likely date back to pagan Baltic times, when grain and seed rituals marked winter’s turning point. When Christianity spread through Lithuania, these ritual foods were incorporated into Christmas Eve customs.