THE ESSENCE OF JAPANESE CUISINE

Principles of harmony, simplicity, and seasonality guide traditional Japanese cuisine. At its core lies washoku, a culinary philosophy that emphasizes balance, especially the five tastes (sweet, salty, sour, bitter, and umami) and five colors (white, black, red, yellow, and green), and five methods (raw, simmered, seared, steamed, and fried). Japanese cooking is all about respecting ingredients and eating things when they’re at their best. There’s this concept called shun – basically eating stuff when it’s in peak season. So that’s what drives how they plan menus and decide what to buy at the market.

Japanese meals are built around rice – it’s the star of the show, not like Western meals with their appetizer-main-dessert thing. They follow this format called ichijuu sansai, which just means ‘one soup, three dishes.’ So you get miso soup, steamed rice, and three side dishes, a selection of protein or vegetable base. What’s this framework for? Instead of focusing on protein as the main, it balances the nutrition: ensures a mix of carbs (rice), protein (fish/tofu), fiber (vegetables), and probiotics (miso/pickles). It also allows for control of portions as dishes are small and prevents overeating.

Breakfast in Japan is a simplified version of the traditional meal, including steamed rice, miso soup, grilled fish, pickled vegetables, and perhaps tamagoyaki, a rolled omelet.

Lunch really depends on whether you’re going traditional or modern. Traditional lunch is similar to breakfast, just with different dishes. Modern lunch centers around single-bowl meals – donburi, ramen, or bento boxes that keep everything separate but in one container.

Dinner is where Japanese meals get fancy – they go beyond the ‘one soup, three dishes’ setup, especially for special occasions. It starts with light appetizers or soup, then all the main dishes come out at once (no waiting around like in Western restaurants), and wraps up with rice, pickles, and tea to finish things off.

Throughout all meals, certain constants persist: rice serves as the neutral base, the anchor of the Japanese meal that balances stronger flavors, pickled vegetables aid digestion and cleanse the palate, and tea provides a gentle conclusion.

GRAINS IN JAPANESE CUISINE

Rice is what Japanese people eat every day, in many cases, 3 times a day, as rice is not just a side, but the center of the dish. It is so central that the word gohan means both ‘cooked rice’ and ‘meal’ itself.

Rice in Japan is steamed and served plain with nearly every meal, transformed into sushi rice, seasoned with rice vinegar, onigiri rice balls, chirashi bowls, and fried rice. Rice is processed into sake rice wine, mirin sweet rice wine for cooking, rice vinegar, and mochi, pounded rice cakes. Fermented grains are also important: rice koji molds transform soybeans into miso and soy sauce; sake brewing relies on polished rice’s starch-to-sugar conversion.

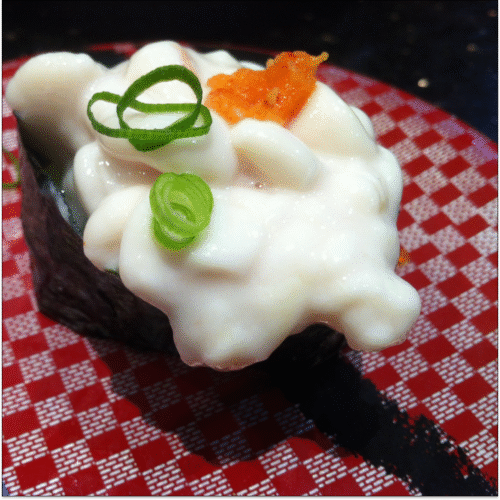

Even the Japanese word sushi refers to the flavored rice. The raw fish is just an addition. Sushi is the international face of Japanese food. Sushi, which we recognize today, emerged as fast food for busy Tokyo workers in the 1800s. Street vendors sold it from portable stalls, making it accessible and casual. In Japan, sushi is only one type of specialized meal or occasional treat rather than everyday food.

Different regions developed distinct styles – Tokyo’s edomae style, Osaka’s pressed sushi, chirashi scattered sushi, maki rolled sushi, tekone marinated tuna sushi, and many others. In Japan, sushi is always prepared by a dedicated craftsman, shokunin. A years-long apprenticeship is required to become a sushi chef.

Wheat appears as flour for making noodles, tempura batter, and confections. Barley is used in teas like mugicha, a popular summer drink.

Noodles arrived in Japan around 800 AD from China and were quickly adopted due to their flexibility. Soon, noodles became ‘a standard dish for most Samurai’ because they met dietary needs as a relatively healthy food that wasn’t greasy. The three main Japanese styles are soba, udon, and ramen:

– Soba – buckwheat noodles of ancient origins, often served cold with dipping sauce or in light broths that emphasize buckwheat earthy flavor.

– Udon – thick wheat noodles, introduced by Buddhist monks from China who believed the thick noodles would help them stay satiated during fasting. Udon has been loved by the entire Japanese population for generations, for its thick, chewy texture and mild flavor.

– Ramen is the most modern version of Japanese noodles; they began as ‘Chinese soba‘ in the 18th century. Japanese cooks adapted Chinese noodle soup by adding fermented miso paste for extra umami.

Tempura is one of the few successful foreign culinary adaptations. Considering Japan’s long period of isolation, it’s quite exceptional in Japanese food history. Tempura was imported in the 16th century when Portuguese missionaries introduced deep-frying via their dish peixinhos da horta – vegetables battered and fried during Catholic Lenten fasting periods. Initially considered a luxury due to expensive oil, it became accessible as fast food sold at outdoor stalls alongside soba and sushi. Today, tempura provides peace of mind for those uncomfortable with raw fish, appears in tendon (tempura rice bowls), tempura udon/soba, and various combination dishes.

What about the world’s major staple – bread? The Japanese do eat bread, but its significance is far from that of rice. Bread arrived via Portuguese traders, but it didn’t become mainstream until later. Now bread in Japan is more of a side snack, convenience food for sandwiches, or a supplement, not a complete meal like rice.

PRODUCE IN JAPANESE CUISINE

Japan was effectively vegetarian for 1200 years due to Buddhist influence and meat taboos. This created sophisticated vegetable-based cooking that is still important today.

There is a wide variety of veggie pickling techniques, including vinegar, miso, rice bran, salt, malted rice, mustard, and sake lees (nutritious, paste-like residue left over after pressing the fermented mash in sake production), aimed at preserving vegetables through winter, imparting unique flavor and nutrition. Fresh vegetables are seasonal markers – for example, takenoko (young bamboo shoots) symbolizes spring more than any other vegetable.

Most traditional washoku staples are daikon radish, negi, a long, thick Japanese onion, napa cabbage, a thin and less seedy Japanese cucumber, slender and less bitter Japanese eggplant, and sweet potato.

The top four ways to prepare vegetables in Japan:

– ohitashi – vegetables are lightly blanched, chilled, and served with a delicate dashi-soy or sesame dressing

– nimono – root vegetables or greens are simmered in a dashi-based broth with soy sauce and mirin, creating tender, umami-rich flavor

– tsukemono – quick–pickled or fermented vegetables, seasoned with salt, vinegar, or miso, adding a crunchy, tangy contrast to meals

– yasai itame – a simple stir-fry with sesame oil, garlic, and soy sauce.

Long ago in Japan, fruits were called ‘water sweets’ and were categorized as confections in Japanese culture. Prior to the Meiji era (before 1868), persimmons and nashi were the main fruits that people enjoyed, with many introduced from abroad after the Meiji era and adapted to the Japanese climate. Fruits in Japan are seen as a suitable gift because it has a seasonality and allow people to experience the colors, smells, and tastes of that season. Mandarin oranges mikan, melons, persimmons, strawberries, ume plums, apples, grapes, apricots, watermelons, and yuzu are the most popular locally.

Sea plants (seaweed) are important in Japanese cuisine, both as a flavor foundation and for their nutritional value. Kombu, nori, hijiki, and wakame are offered to the gods in Shinto rituals, which shows how sacred these sea plants are in Japanese culture. Kombu is especially important because it gives dashi that deep, savory umami. Fun fact: It was actually kombu in dashi that inspired Japanese chemist Kikunae Ikeda to figure out what umami was all about. He discovered it came from glutamates in the kelp, which led him to create MSG (Monosodium Glutamate, a flavor enhancer).

Seaweed is thought to be a contributing factor to the long life expectancy of people in Japan, as it is low in calories and rich in vitamins, minerals, and fiber. Traditional Okinawan cuisine relies more on kombu per household than any other prefecture and enjoys the title of having the world’s longest life expectancy.

FERMENTED FOODS IN JAPANESE CUISINE

While Westerners love fermented yogurt, sourdough, beer, soy sauce, or tsukemono, the slimy, sticky natto, and fermented dried fish kusaya may be a bigger hurdle. These tend to challenge Western palates due to strong smells, textures, or acquired tastes. Main Japanese fermented foods are soy sauce shoyu, fermented soy paste miso, fermented tofu sufu, and fermented soybeans natto, all of which are traditional foods. Tsukemono, Japanese pickles, are either fermented with salt and vinegar or with koji mold. Sake, rice vinegar, mirin, katsuobushi bonito flakes, umeboshi pickled plums, and various seafood products are also fermented.

Given the history of fermented foods in Asia, it is surprising that Japan, for example, does not recommend this as a category in their food guides. With few exceptions, fermented foods are generally absent as a recommended category of food for daily intake (source).

MEATS IN JAPANESE CUISINE

Japan has the shortest history of eating meat compared to other Asian countries due to Buddhist vegetarianism, political idealism, and scarcity. In the 7th century, a ban on the consumption of four-legged animals took effect, but left fish out of it. Traditionally, the Japanese shunned meat as a result of adherence to Buddhism, but with the modernization in the 1880s, meat became common. The shift, though, happened slowly; only 2.8 grams of meat was the daily amount consumed by the average Japanese in 1939. Household meat consumption in Japan did not surpass that of fresh fish consumption until 2007.

The three main types of meat eaten in Japan are beef, pork, and poultry, with chicken being consumed the most. Pork was previously Japan’s most consumed meat for many years before being overtaken by chicken. Beef is a premium choice; Japanese wagyu has developed some of the world’s most prized beef varieties, representing the pinnacle of Japanese meat culture and a major export product.

FISH AND SEAFOOD IN JAPANESE CUISINE

Historically, Japan did not have a lot of nutrient-dense food on land, so there was a time when the sea was the main food source. This geographic necessity evolved into culinary culture. Fish consumption in Japan is still among the highest in the world – an average of 84 g of fish and 41g of seafood every day, which is more than in most other developed countries. Among Japanese choices, salmon and trout are very popular, as well as bluefin tuna, mackerel, butterfish, octopus, and salmon roe.

Japan likely leads the world in raw fish consumption in absolute terms, but Japanese people actually eat far more cooked fish than raw. Daily meals feature cooked fish: grilled for breakfast, fish in soup, tempura, simmered fish dishes, and fish cakes. Raw preparations are more often for special occasions or dining out.

EGGS AND DAIRY IN JAPANESE CUISINE

Japan definitely eats way more eggs than most countries. The average person goes through about 320-340 eggs per year, basically one egg every day. Those old meat bans probably played a part in this, but they aren’t the sole reason.

Raw and lightly cooked eggs are quite distinctive. Take tamago kake gohan – just a raw egg stirred into hot rice with some soy sauce, and you get this creamy, super comforting dish. Raw or lightly cooked eggs also work like dipping sauces for sukiyaki and other hot pot meals, where the egg coats the hot food and cools it down. Food safety standards make this totally safe to do.

Dairy used to be basically nonexistent in Japanese cooking. Buddhist beliefs weren’t big on dairy, and many people have lactose intolerance. After World War II, dairy became more common, but it’s still not really a centerpiece.

OILCROPS AND SWEETS IN JAPANESE CUISINE

Soybeans are absolutely central to Japanese cooking – they show up everywhere as soy sauce, miso, soy milk, tofu, natto, edamame, yuba, and kinako powder. Soybeans provide the umami foundation that defines Japanese flavor profiles.

Unlike Western meals, where dessert caps off dinner, traditional Japanese meals don’t end with sweet courses. Japanese sweets are closely tied to the tea ceremony and seasonal awareness. These delicate confections are typically made from sweet bean paste anko, rice flour, and sugar, with minimal use of dairy or eggs. Examples include mochi, dorayaki, and intricate seasonal wagashi.

Modern Japan has totally embraced dessert culture and created matcha-flavored everything, Japanese-style cheesecakes, and elaborate parfaits. Specialty dessert shops are now incredibly popular – it’s like they’re making up for lost time.