THE ESSENCE OF ITALIAN CUISINE

Clarity and respect for ingredients are what Italian cuisine is about. Food highlights immediacy – the tomato that tastes like summer, the olive oil that is green and peppery, the pasta dough that speaks through its texture rather than elaborate sauce. In a way, it’s a cuisine of restraint: Italians are famous for saying ‘less is more’ at the table, and you see that in a plate of spaghetti aglio e olio or a caprese salad. The point is not to overwhelm you, but to win you over with honesty on the plate.

Another defining trait is regional identity. While Chinese or Indian cuisines are also very regional, Italian food has made this diversity central to its identity, and Italians fiercely guard these local distinctions.

Globally, cuisine stands out for accessibility. Dishes travel well: pizza, pasta, espresso, gelato – they adapt without losing their character. Italian food managed to be both very traditional and incredibly exportable, and that balance is rare.

Italians are quite structured when it comes to meal courses, though the degree of strictness depends on context. At home, meals are often simpler -maybe pasta followed by salad and fruit. Dishes come in relatively small portions and can be mixed and matched. But traditionally, and especially in formal settings, there’s a clear sequence that Italians take seriously.

The classic order is an aperitif, meant to open the stomach before dining. Then follow the meals: antipasti (small starters), primo (pasta, risotto, or soup), secondo (meat or fish), with contorno (vegetable sides) served alongside, then dolce (dessert), sometimes followed by fruit, coffee, and maybe a digestivo. Importantly, pasta or risotto is never the main course – it’s always a first course, something that often surprises foreigners.

GRAINS IN ITALIAN CUISINE

Italian cuisine’s global identity is tied to wheat through its use in pasta. Pasta formed in Italy through a blend of cultural exchanges and farming adaptation, rather than a single origin story. The earliest dried pasta was introduced by Arabs in Sicily during the Middle Ages; they brought techniques for making durable, dry noodles using durum wheat, which was good for storage and long journeys. Over time, this pasta-making spread from Sicily to other regions, where durum wheat was plentiful, and eventually became a central part of Italian food culture. This gradual process rooted pasta firmly – it was already an established symbol long before the myths about pasta imports arrived.

Two kinds of wheat are primarily grown in Italy: grano duro – hard wheat – called semola, semolina or durum; and grano tenero – soft wheat, also known as common wheat.

The vast majority of dried pasta is made from durum wheat – its strong gluten ensures pasta keeps its shape and al dente texture after cooking. Italian law actually requires it if the pasta is produced and sold in Italy.

But when it comes to fresh pasta (pasta fresca), especially in northern Italy, you’ll often find it made with soft wheat flour (tipo 00) and eggs – like tagliatelle, pappardelle, or filled pastas like tortellini and ravioli. These rely on a more delicate dough, which soft wheat provides.

Many Italians eat pasta at least three times a week or more, but they keep an eye on their portions (80-100 grams / 2.8–3.5 oz.). Every other village in Italy has at least one traditional type of pasta, so there are countless types and more than 350 shapes. Not only do the region and tradition define what pasta is to be used – it also defines sauce compatibility, textural variations, and visual appeal. For example, long and thin pasta like spaghetti is ideal for oil or tomato-based sauces, shorter-rigged pasta like penne is suitable for thicker, chunky sauces.

There are quite a few misconceptions about Italian pasta, and so here’s the perfect place to address them.

- Pasta is not the main course. In Italy, pasta is a primo piatto (first course), not the centerpiece. The main course is usually meat or fish with vegetables.

- Pasta should not drown in sauce. Italians use just enough sauce to coat the pasta. The pasta itself is the star, not the topping.

- Breaking spaghetti before cooking is a culinary sin in Italy. Long pasta is meant to stay long, twirling it is part of the experience.

- Pasta Alfredo is not a classic Italian dish. The heavy cream-based Alfredo is American. In Italy, fettuccine al burro is simply pasta tossed with butter and Parmigiano, no cream. The same goes to spaghetti and meatballs, which is not a traditional Italian meal. Meatballs (polpette) exist in Italy but are served separately, not with pasta.

- Pasta does not come with garlic bread as it doesn’t exist in Italy. Bread is served plain on the side and used to mop up sauce at the end; this is called fare la scarpetta.

- Cheese does not go on every pasta dish; it is never added to pasta with seafood, as it clashes with the delicate flavor of seafood.

- Pasta must be not cooked until soft. Italians eat pasta al dente – firm to the bite. Overcooked pasta is a sign of carelessness.

Wheat consumption extends to breads and bakes. Italian breads are usually rustic, made of few ingredients – flour, water, yeast, salt, olive oil. They’re also diverse regionally: focaccia in Liguria, altamura bread from Puglia, or pane toscano with little to no salt. Italian cakes are often festive breads rather than layered confections. Panettone, pandoro, colomba – all are yeasted, fluffy, and seasonal.

Pizza sits on the same spectrum as focaccia, schiacciata, and other regional flatbreads, except that pizza is the whole meal, the most iconic Italian culinary export. Italians love pizza, but they don’t eat it every day. In fact, for most people, pizza is more of a weekly treat. Let’s address some misconceptions about pizza.

- Traditional Italian pizza is minimalist – like Margherita with tomato, mozzarella, basil. The focus is on dough quality and balance, not excess.

- Pepperoni is an American topping. In Italy, peperoni means bell peppers. If you order a pizza peperoni, you’ll get vegetables, not salami.

- Thick, fluffy crust is not the universal standard. In Naples, pizza is thin and soft in the center, with a puffy outer crust (cornicione). In Rome, it’s crispier and thinner. Deep-dish styles are not Italian.

- Pineapple (pizza hawaiana) is not Italian at all; it was invented abroad, and most Italians see it as an odd pairing.

- Pizza is not necessarily eaten by hand. Pizza served in restaurants usually comes as a whole pie, eaten with a knife and fork. Street pizza (pizza al taglio) is the version sold by the slice.

- Extra cheese doesn’t make pizza more Italian. Italians use mozzarella sparingly and don’t overload. Quality trumps quantity.

In Italy, plain steamed rice is not typical. When rice is featured on menus, it’s most likely to be arborio and carnaroli varieties, which absorb liquids and remain pleasantly tender. Rice is used in creamy risottos (cooked in broth with various ingredients), arancinis (fried balls with filling), or risi e bisi (rice and fresh beans dish with prosciutto).

Polenta is uniquely popular as the main corn product in Italy. After maize was introduced from the Americas, it was widely cultivated in northern Veneto and Lombardy. It yielded more and grew faster than traditional millet, rye, and wheat. Farmers ground the corn into a coarse meal, and polenta soon became a staple for rural communities and the working class. Its lasting popularity also comes from being easy to digest, naturally gluten-free, and wonderfully versatile – it can be consumed creamy, set and sliced, grilled, or even fried.

VEGETABLES IN ITALIAN CUISINE

Pulses are important in the traditional diet, especially in regional and peasant cooking. Cannellini beans, borlotti beans, fava, chickpeas, and lentils are nutritious source of plant-based protein and fiber, yet very underrepresented in fine dining and haute cuisine in Italy. Every region of Italy has its signature legume-based dishes, like pasta e fagioli (pasta with beans), minestrone (vegetable and bean soup), ribollita (leftover soup).

The connection between vegetables and the season is fundamental. Their preparation is relatively minimalistic – vegetables with quality olive oil, herbs, and sometimes cheese or bread, ensuring they remain central and not overcooked. Aslo, the Italian approach is to highlight one or two vegetables at a time and not mix many together.

Spring comes with asparagus, peas, and artichokes. Peppers and eggplants are enjoyed in summer, tomato dressings and sauces are used all year round. Broccolis, cauliflowers, porcinis, and cremini mushrooms signal the arrival of fall. Carrots, winter squashes, and savoy cabbage round up a winter meal. Italy also uses unique vegetables like friarielli (broccoli rabe), cicoria (chicory), finocchio (fennel), cavolo nero (Tuscan kale), and fiori di zucca (zucchini blossoms).

People in Italy really love mushrooms—porcini are a big favorite. And when it comes to truffles, Italy’s reputation is hard to beat, with those famous white truffles from Piedmont stealing the spotlight. In Umbria the truffle is traditionally called tartùfro, fragrant stone. The region has been associated with truffles for centuries, but also other regions in Italy use truffle festivals (autumn especially) to draw visitors. Truffle hunting is a traditional practice, involving specially trained dogs that replaced pigs. The strong truffle mimics the scent of certain male pig pheromones, making pigs natural truffle hunters. However, dogs are preferred today as they are easier to handle and less likely to eat what’s found.

Fruits are an integral part of a table setting in the raw form – as a healthy snack, as a pairing for cheese or ice cream. Jams and jellies accompany bread and coffee for breakfast, and compotes; dried fruits are used in salads, gelato topping, or baking. Italian desserts use fruits extensively: fruit tarts, fruit-filled pastries, and fruit-based gelato (ice cream).

Grapes are grown to produce wine and the famous balsamic vinegar – a traditional condiment from whole, freshly crushed, cooked, concentrated, and aged grapes. The vinegar aging is lengthy and involves aging in wooden barrels for a minimum of 12 years (for traditional balsamic vinegar of Modena) or up to 25 years for the highest quality varieties. Some batches are started and labeled when a child is born in a family, with the vinegar maturing alongside the child and sometimes not reaching perfection until decades later, becoming a true family heirloom. Balsamic vinegar is of dark color, sweet, rich flavor, and is used to enhance salad dressings, marinades, drizzled over berries, stirred into a risotto, tossed with Brussels sprouts, and many other uses.

MEAT IN ITALIAN CUISINE

By meat consumption Italy is around the global middle – lower than top countries like the U.S., Australia, and Spain, but higher than many Asian and some African countries. Pork is ‘the meat’, an essential part of farming families for generations. It’s important that not every family may have had hundreds of farmed pigs; sometimes, a single one would be butchered and shared with neighbors, and every part of it would be used for good. One pig could have fed a family long, as small amounts of fresh or preserved pork enhanced otherwise vegetarian dishes. Pork blood is used to make sanguinaccio (sweet blood pudding) and salsiccia al sangue (blood sausage), and chops and belly are turned into roasts.

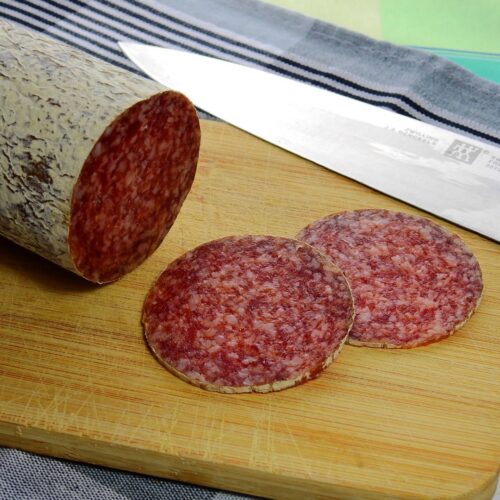

Italian cuisine stands out for its use of cured meats, the creative integration of meat as a flavoring (rather than a main component), and its strictly traditional methods that protect products. The best parts of the pig don’t just get eaten right away—they’re transformed through time-honored curing and drying, turning into mouthwatering sausages and salamis. Every region has its own specialties, so you’ll find everything from famous prosciuttos like Di Parma and San Daniele to beloved salamis like Genoa and Sopressata.

Beef is used in classic dishes such as bistecca alla fiorentina and ossobuco, veal appears in Milanese and Roman specialties, and lamb is especially valued in Central and Southern Italian traditions (e.g., abbacchio alla romana). Chicken and other poultry are common but less central, often used in rustic dishes like pollo alla cacciatora.

Game meats are pretty popular and are eaten seasonally: wild boar, venison, hare, pheasant, quail, and wild rabbits.

FISH AND SEAFOOD IN ITALIAN CUISINE

Fresh seafood used to be a privilege of the coast, so traditions around preparing seafood developed—or didn’t—depending on where you were in Italy.

Italian cooks use seafood in ways that uniquely highlight freshness and natural flavors. For example, pasta con bottarga uses cured mullet roe grated over pasta for a rich, briny punch that’s distinctive to Sardinia and Sicily. Venice is famous for creamy baccalà mantecato, where dried salted cod is whipped into a smooth spread and served with polenta. In the south, sea urchins are eaten raw or tossed with pasta – especially in Puglia, where they’re a seasonal delicacy enjoyed straight from the shell. Italians also love crudo di mare, serving raw scallops, shrimp, or even octopus with lemon and olive oil to for the freshest catch. And throughout coastal towns, mixed fried seafood fritto misto di mare is a staple. Small, oily anchovies are popular salted, marinated, or packed in oil, showing up in pizza Napoletana, spaghetti alla puttanesca, and bagna cauda – a warm dipping sauce from Piedmont. They’re used to add depth to sauces, soups, and salads, often melting into the background to create bold umami notes. In coastal regions, fresh anchovies may be enjoyed simply grilled, fried, or pickled.

MILK AND DAIRY IN ITALIAN CUISINE

Cultured milk, in the form of cheese, is the heart of Italian cuisine. Why does Italian cheese taste so utterly different from cheeses elsewhere, even when the same species of animal might be used?

The tradition of cheese-making is a heritage from the ancient Romans, who elevated cheese-making to a new level. Today, Italy has the highest variety of cheeses worldwide, with over 2500 sorts, 300 kinds with protected designation of origin, and even 52, protected under European Union law! Italian cheeses are well known and appreciated worldwide: sharp and crumbly parmigiano-reggiano, soft, creamy mozzarella di bufala, hard sheep milk pecorino, buttery gorgonzola, robust caciocavallo.

Flavors and textures of those cheeses are the result of animal breeds, pastures, microflora, and rigorous tradition. Let’s take parmigiano reggiano: only specific heritage cows – like the Reggiana, Bruna Alpina, or Bianca Modenese – are valued for their milk with higher casein and fat content, which means the cheese ages with greater complexity than milk from mass-market Holsteins. Even what the cows eat – lowland grass or mountain wildflowers – imparts distinctive notes. Also, the tradition of semi-skimmed milk (morning whole, evening skimmed) gives a layered profile.

Then there are cheeses shaped by the local geology: pecorino carmasciano, produced from sheep grazing in the sulphur-rich Mefite d’Ansanto valley, absorbs environmental minerals that give sharp complexity.

OILS, NUTS AND DESSERTS IN ITALIAN CUISINE

Olive oil is essential to Italian cooking, no matter the region. Nearly all Italian regions produce their own olive oil, harvested from more than 500 types of locally grown olives. Northern Italian oils from Liguria and Lombardy tend to be mild, delicate, and buttery, while oils from Southern Puglia, Sicily, and Calabria are bolder, robust, peppery, and often have sweet or herbal notes. Though Italian cuisine also uses butter, olive oil is a must-have kitchen staple used for sautéing and dressing to finishing with a distinctive Mediterranean character.

Nuts are very diverse in Italian cooking. They feature the infamous pesto sauce; toasted nuts are served with pasta; chopped nuts are used in salad dressings, cookies, tarts, and nougats. Italian gelato often includes nut-based flavors of pistachio or hazelnut.

Italian sweets are usually less sweet, with a focus on nuts, ricotta, chestnuts, and fresh or dried fruits. Many classics – such as tiramisù, panna cotta, or gelato – use few, high-quality ingredients.

The true genius of Italian desserts is in their balance: light and creamy or crisp and flaky, with contrasts like the crunchy shell and silky filling of a cannolo or the delicate set of panna cotta paired with tart berries. What is served in Sicily or Naples may be completely unknown further north, so every local bakery feels like a window into its own unique culinary environment.