THE ESSENCE OF INDIAN CUISINE

Indian cuisine is fundamentally plant-based, though not for lack of options. Plants – grains, pulses, vegetables, roots – form the spiritual and practical foundation. Rice, wheat, millet. Dozens of lentil varieties. Cow’s milk, but not the cow itself. Even in regions where meat is common, it takes a backseat to the dal (dried split pulses), sabzi (cooked veggie dish), and roti (unleavened flatbread).

Long before anyone coined macronutrients, Indian cooks were already serving complete meals: protein-rich lentils, fermented batters full of probiotics, fiber-packed vegetables, cooling yogurts, and energy-giving grains. It grew from Ayurvedic principles where food balances the body through qualities like hot, cold, dry, and oily, and every bite served a purpose beyond taste. The thali perfectly demonstrates this logic. A round plate carrying many small portions in deliberate order represents all six tastes. There’s always a balance: dry curry against runny dal, fried items with pickles, and cooling raita (a refreshing condiment) to offset the heat.

The techniques matter just as much. Take tadka – that moment when spices hit hot oil and transform instantly, releasing compounds that define the dish’s character. There’s dum for slow-cooking in sealed pots, bhuna for aggressive sautéing until oil separates, tandoor for char and smoke, and handi for deep-vessel gravies. Each technique exists to unlock specific qualities in ingredients.

The morning starts with tea and perhaps a light snack, followed by a substantial main meal. The evening meal is lighter than the morning one. This pattern aligns with Ayurvedic principles that suggest eating the heaviest meal when digestive fire is strongest, mid-morning to early afternoon.

THE AUTHENTICITY OF INDIAN CUISINE

Authentic Indian dishes differ from those served abroad in several ways, lets try to break them down.

SPICE LAYERING. In India, spices are added in a specific order, often whole at first, then ground. Abroad, spices are often pre-mixed, added all at once, or used sparingly.

DAIRY FATS. Use of ghee, homemade yogurt, and malai (cream skimmed from milk). Abroad, butter, cream, and even sour cream or heavy cream are used instead. Ghee is often replaced with oil.

SWEETNESS AND CREAMINESS. Authentic sweetness is rare and reserved for specific dishes. Creaminess is achieved through the use of nuts or slow cooking. Abroad, dishes like butter chicken are often overly sweet and creamy to suit Western palates.

HEAT AND TANG. Chilies, black pepper, raw mango powder, tamarind, or dried pomegranate seeds are used precisely depending on the region. Abroad, chili is often toned down or replaced by cayenne or paprika. Tang is usually missing or replaced with lemon/lime juice.

BREAD AND RICE VARIETY. Locally, each dish is paired regionally – sarson da saag (mustard greens dish) with makki di roti (corn flour flatbread); hyderabadi biryani (rice dish) with mirchi ka salan (green chilies curry). Rice types like seeraga samba or gobindobhog are used, while abroad, generic naan and basmati rice are served with everything, regardless of the dish’s origin.

REGIONAL VARIETY. Locally, there’s enormous micro-regional variety. Abroad, menus are usually limited to North Indian-style curries (tikka masala, saag paneer, dal), with little representation of street food or East/South Indian cuisine.

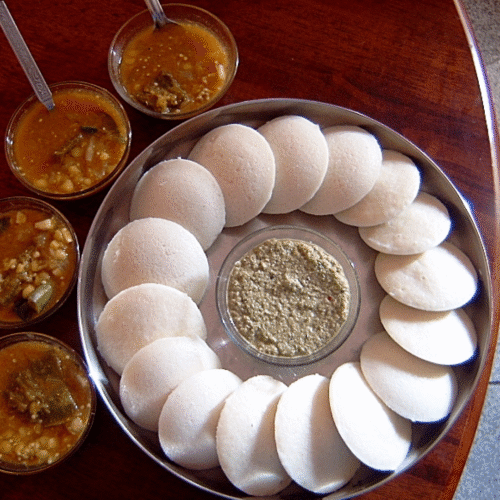

FRESHNESS AND FERMENTATION. Locally, spices are freshly ground into pastes, and batters are live-fermented (idli, dosa); pickles (achaar) are central. Abroad, pickles are often pasteurized or vinegar-based, and dosa batter is sometimes pre-made, lacking fermentation complexity.

GRAINS IN INDIAN CUISINE

India uses a wide variety of grains as staples: rice, wheat, millet (bajra pearl millet, ragi finger millet), corn, barley, and regional amaranth. Different regions became specialists – Bengal with rice, Punjab and other Northern regions with wheat, Karnataka with ragi, Rajasthan with bajra. However, rice absolutely dominates: as a practical base of most meals, flattened rice (poha) for breakfast, puffed rice (murmura) for snacks and street food, flour for dosas, idlis, and sweets.

India has perhaps the world’s most sophisticated grain fermentation. Dosa, a savory crepe made from ground black gram and rice, and idli, savory rice cake batters, dhokla, a savory sponge dish, fermented rice – these are complex biotechnological processes that transform grain nutrition and digestibility. Few other cuisines utilize fermentation as extensively for grains as this one.

Indian breads are eaten extremely fresh. A roti or paratha (unleavened flatbread of flaky texture) must be cooked moments before serving. This ‘hot off the griddle’ approach is so important that day-old bread is already inferior. Most Indian breads are unleavened or use alternative fermentation methods. When Indians ferment, it’s often through natural fermentation using rice-lentil batters, rather than commercial yeast, to create different textures and flavors entirely. Indian breads actively use millet, corn, rice, sorghum, and combinations thereof. A single Indian household might use five different grains for different breads in one week.

- Roti/Chapati is the everyday bread – unleavened, rolled thin, and cooked on a dry griddle (tawa). It’s the workhorse of North and Central Indian meals, made fresh for each meal.

- Naan represents the restaurant face of India – leavened with yogurt or yeast, traditionally baked in a tandoor. The high heat creates the characteristic charred spots and chewy texture.

- Paratha comes in countless variations – plain, stuffed with vegetables, layered with ghee. It’s richer and more substantial than roti, often eaten for breakfast or special meals.

- Puri is deep-fried and puffed into crispy balloons. It’s festive food, served at celebrations.

- Makki ki roti from Punjab uses corn flour and requires skill to roll without cracking. It’s traditionally paired with sarson da saag (mustard greens).

- Bajra roti made from pearl millet is common in Rajasthan and Gujarat – denser and more nutritious than wheat bread.

- Jowar roti uses sorghum, popular in Maharashtra and Karnataka.

PRODUCE IN INDIAN CUISINE

Indian cuisine is structured around what’s naturally available when. Due to India’s vast climatic zones, the variety of produce is enormous – from tropical fruits and coconuts to temperate vegetables and herbs in the Himalayas. Produce choices are tied to Ayurvedic principles, for example bitter gourd (bitter melon) and fenugreek in summer to cool the body, yam and mustard greens in winter for warmth, only few cuisines make such conscious seasonal-medicinal use of produce.

Extensive pickling achar of vegetables and fruits is common, usually in mustard oil, spices, acids. E.g., mango pickle, lime pickle, carrot pickle, green chili in vinegar. Indian pickles are very often oil-preserved, while other cultures more extensively use vinegar or brine. Vegetables are nearly always paired with lentils (dal) or flatbreads.

Some of the most popular produce in the cuisine of India are:

- Potatoes: not native, but absolutely essential in North Indian cuisine.

- Onion – base for curries, pickles, fried garnishes.

- Tomato – curry gravies, chutneys, rasam (spicy, tangy, and thin soup).

- Green chili – heat agent in most dishes, pickles, chutneys.

- Garlic – aromatic base, chutneys, pickles, infused oils.

- Spinach – pureed gravies, dals, stir-fries.

- Eggplant – roasted mash (baingan bharta), curries, fried.

- Cauliflower – dry curries, pakoras (deep fried snack), aloo-gobhi (dish of potatoes and cauliflower), biryani filler

- Okra – stir-fried with spices, stuffed, curried.

- Green mango – pickles, lentils, chutneys, summer drinks.

- Bitter gourd: essential for its medicinal properties, found across India but prepared differently by region.

- Bottle gourd: common across North India, essential for light, digestible meals.

A dry curry refers to a dish where vegetables, meat, or legumes are cooked with spices until the moisture evaporates, leaving a thick, clinging masala or no sauce at all. It’s the opposite of a ‘gravy’ curry. Dry curries are common in home cooking, especially for everyday potato, okra, or cabbage. Dry curry is not a traditional culinary term – it’s more common in English-language cookbooks to distinguish sauceless versions. In Indian kitchens, such dishes are simply called sabzi or sookhi sabzi (dry vegetable).

Though now indispensable, chillies were introduced only about 500 years ago by the Portuguese. Before that, heat in Indian cuisine relied on black pepper and long pepper (pippali). Rapidly chillies became a cheap and accessible spice, especially for lower-income groups, when other spices were unaffordable. Red dried chillies are believed to ward off the evil eye (nazar) in Hindu homes. It is common to see strings of chillies with lemons hanging in vehicles or doorways for protection. Chili pepper has also entered everyday language, with phrases like mirchi lagi kya? (did you feel the burn?) used humorously to ask if someone is offended.

Indian cuisine uses some of the spiciest chilies in the world, like Bhut Jolokia ghost pepper and Naga King, but not uniformly across the country:

- Extreme heat: Nagaland, Manipur, Andhra Pradesh, parts of Maharashtra

- Moderate heat: Gujarat, Bengal, Kerala

- Mild/minimal heat: Kashmir, Karnataka Udupi cuisine, Sattvic/Jain traditions

In many other cuisines fruits are eaten fresh or in desserts, but India incorporates fruits into main courses, curries, pulaos, and chutneys extensively. For example, pineapple pulao combines sweet pineapple with spices and rice, and mango is used in tangy chutneys and yogurt-based drinks like lassi.

MEAT IN INDIAN CUISINE

In Hindu tradition, the cow is often called gaumata – cow mother, a maternal figure that nourishes humanity. Slaughtering a cow for meat requires killing, which violates the principle of non-violence; therefore, the Hindu communities do not eat beef.

Meat is not a minimal choice, but rather one that is selectively consumed across India. Hindus generally avoid beef as cows are sacred, Muslims avoid pork, and many communities practice vegetarianism or limit meat intake on certain days.

Northeastern states, Kerala, West Bengal, Goa, and Nagaland have higher meat consumption, with up to 20-25% of food expenditure spent on meat, eggs, and fish. Those regions had lesser influence of vegetarian Brahminical norms, have more widespread Christian or Muslim communities, who traditionally eat either beef or pork. Consumption is also rising steadily due to urbanization, better income, changing lifestyles, and greater availability of hygienic meat products.

Chicken dominates the domestic market, India is also a major exporter of buffalo meat (often labeled as beef internationally). Unlike in many Western countries, where mutton means older sheep meat, in India, ‘mutton’ almost always means goat meat, specifically from young male goats. Sheep meat is rarer and more expensive, so goat dominates. Mutton dishes are associated with celebrations, festivals, and special occasions.

When Indian meat dishes are prepared abroad, it’s usually the butter chicken or tandoori-style roasts, even though this is not the most common method within India. For Western diners, tandoori evokes visual drama – colors, grill marks, sizzle. It fits Western expectations of meat: grilled, smoky, and protein-forward.

Meat is usually braised, stewed, fried, or simmered in spiced gravies. Locally, everyday Indian meals are moist, saucy, and gravy-rich, which pair well with rice or flatbreads.

Braised in gravy is common across India: meat is simmered in a masala base of onion, ginger, garlic, and spices, like rogan josh (Kashmir): lamb in yogurt-spice gravy, chicken curry (pan-Indian): basic stewed chicken in spiced tomato-onion base, mutton kosha (Bengal): slow-cooked until the sauce clings.

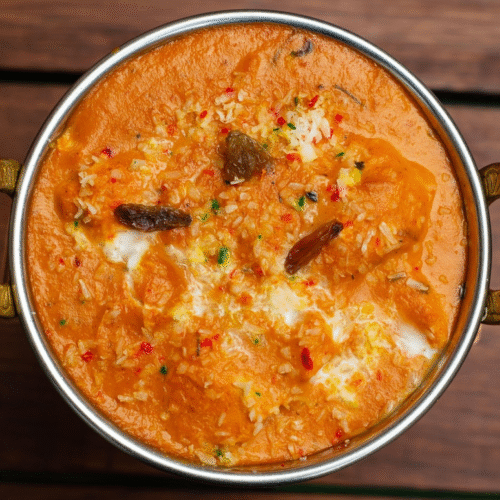

Meat is marinated in yogurt and spices, then partially cooked and layered with rice, sealed, and steamed (dum method) in hyderabadi biryanis, raw meat layered with rice and cooked, awadhi biryanis, pre-cooked meat layered with rice.

Ground meat keema is used in fillings, kebabs, and curries, it is mixed with spices, legumes, or binders like chana dal (husked chickpeas). Iconic examples are keema paratha, stuffed flatbread, shami kebab or seekh keba, pan-fried or tandoor-cooked, keema matar, minced meat with green peas.

What may surprise is that the widely internationally presumed Indian chicken tikka masala is not a traditional Indian dish. It’s widely understood to have been invented in the UK, most likely by South Asian (mainly Bangladeshi) chefs catering to British tastes in the 1960s or 70s. The story claims that a British customer ordered chicken tikka (grilled, marinated, boneless chicken) and found it too dry, so they asked for a sauce. The chef improvised by adding a tomato-based cream sauce with spices, and chicken tikka masala was born. Chicken tikka (dry grilled) is traditional in Indian cuisine as well as butter chicken murgh makhani, a Delhi-origin dish from the 1950s, closer in flavor to tikka masala, but with different spicing and history.

FISH AND SEAFOOD IN INDIAN CUISINE

India’s extensive coastline of over 7,500 kilometers provides an incredible variety of seafood. In Kerala, Goa, West Bengal, and the Northeast, fish and seafood are staples of curries, fried fish, prawn masalas, and crab dishes. Mustard oil and panch phoron (whole spice blend, originating from eastern part) distinguish Bengali fish dishes; coconut milk and curry leaves are popular in Kerala; Goa uses kokum (a fruit of tart, sour taste) and fiery spices in seafood curries.

Popular seafood options are kingfish (surmai), pomfret, hilsa, mackerel, prawns, crab, and calamari.

Indian seafood is almost always served with rice, not naan or roti. Fish is often shallow-fried, steamed in banana leaves, or simmered in thick gravies – not grilled or raw. Even in seafood dishes, Indian cuisine incorporates vegetables and legumes, creating more complex, balanced meals rather than focusing solely on protein.

MILK AND DAIRY IN INDIAN CUISINE

In Hindu tradition, milking a cow is a natural, mutually beneficial relationship – the cow provides milk and receives care, protection, food. The act of giving milk is seen as the cow’s service to humanity, and Indian cuisine is truly dairy-forward. Dairy appears in multiple forms:

- Milk is offered to gods, poured over Shiva lingams, mixed with honey and ghee in panchamrita (offering to gods), and used in temple food. It’s not just consumed, it is sanctified.

- Ghee, clarified butter, is a ritual substance, offered to deities and prescribed in Ayurveda.

- Dahi yogurt is eaten daily as a cooling agent, fermented starter, digestive, and base for kadhi (yogurt simmered with spices into a gravy), lassi (yogurt-based smoothie-like beverage), chaas (yogurt diluted with water and seasoned with cumin, coriander, and mint), and curd rice (cooked rice mixed with yogurt and tempered with spices). In the South, a meal is incomplete without curd at the end.

- Paneer (fresh cheese) is a main protein in vegetarian communities, particularly in Northern Mughlai and Punjabi.

- India’s desserts barfi, rasgulla, rasmalai, peda, gulab jamun are based on milk reduction, curdling, or clarification. Other cuisines use sugar, flour, or fruit, but India uses milk as the base medium.

In a hot climate where dairy spoils quickly, India developed methods to ferment, preserve, or clarify milk with the above examples. This contrasts with tropical or subtropical cuisines elsewhere, which largely avoided milk due to spoilage.

NUTS AND DESSERTS IN INDIAN CUISINE

Nuts have a somewhat unexpected role in Indian cooking – they are thickeners, not just garnishes. Ground cashews, almonds, or poppy seeds thicken shahi korma, pasanda, rogan josh. In some regions, they replace cream or flour, giving luxurious body and sweetness. Ayurveda recommends soaking almonds overnight for their benefits to strength, memory, and vitality. Regional variety and scale:

- North: cashew, almond, pistachio in gravies and sweets

- West: peanut and sesame dominate Maharashtrian and Gujarati cooking

- South: coconut is foundational, but cashews are common too

- East: poppy seeds, peanuts in Bengali cuisine, even as paste for fish curries

Indian desserts stand out globally for being milky and dense, sweet-forward, spiced, perfumed, and technically demanding, despite humble ingredients. Built around milk, sugar, ghee, and time, they are intensely sweet, especially traditional ones like jalebi, a crispy, chewy, and sticky confection; gulab jamun, deep-fried balls from milk solids; or boondi laddoo, deep-fried droplets of gram flour batter soaked in sugar syrup. There’s rarely a contrast of tart or bitter to balance the sugar, unlike in Western or East Asian sweets. Cardamom, saffron, rosewater, nutmeg and kewra (fragrant extract from pandanus flower), are common. Indian desserts avoid eggs almost entirely, fruits are rarely a star, with the exception of mango and banana halwa, and chocolate is rare.