Chinese cuisine is based on three principles: grains plus dishes, quick cooking, and sharing. “Grains plus dishes” translates the established Chinese concept (zhǔshí pèi cài), which literally means “staple food accompanied by dishes”. Every meal starts with a staple – rice, noodles, or steamed buns – then variety is added with vegetables, meats, and soups. You will not find large loaves in China; all ingredients are cut into small, uniform pieces, so everything cooks quickly and evenly. Chinese cooks are masters of subtle heat control: quick stir-fries, short braises, and gentle steaming are all demanding techniques to reach the perfect doneness. Meals are served around a round table, encouraging everyone to share.

The idea of balance is always present to some degree. The traditional and symbolic Chinese meals attempt to match these principles:

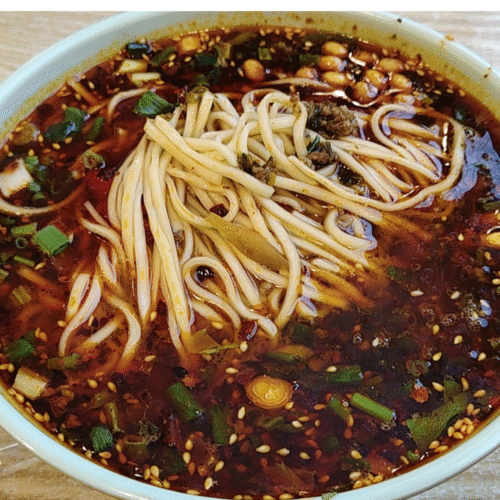

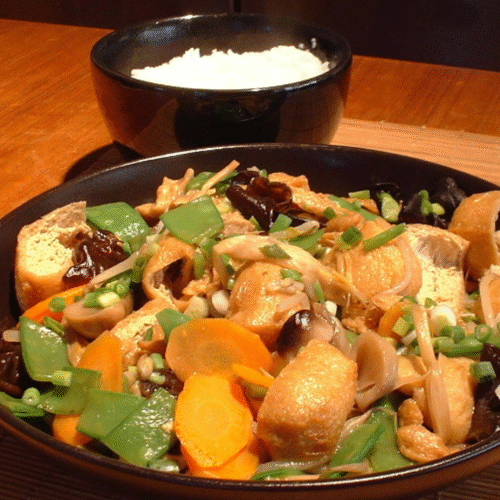

- Texture. Contrast between soft and crisp, tender and chewy, smooth and crunchy keeps a meal interesting. Chinese cuisine treats texture as a core criterion of good cooking. Though all the textures are important, the Chinese have a distinctive appreciation for chewiness. Noodles should be firm and bouncy; fish balls, rice cakes, and sweets are liked for their chew. Many Western cuisines favor tenderness and crispiness, Chinese food aims for the opposite – tension and resistance while chewing.

- Flavor. Balance among the five fundamentals – sweet, sour, bitter, salty, and spicy/pungent is crucial. Each region interprets this differently, but harmony among them defines a good dish.

- Yin and Yang – cooling and warming foods. Meals should balance yin (cool, light, moist foods like cucumber or tofu) and yang (warm, rich lamb or ginger). This harmony supports both digestion and overall well-being.

- Color. A well-prepared meal should ideally have five colors: green, red, yellow, white, and black.

- Aroma. Ginger, garlic, scallion, and sesame oil are used to create a layered fragrance.

In everyday home cooking, families focus more on practical balance: making sure the meal isn’t too oily, too salty, or too monotonous in texture or temperature. The full harmony is more typical of banquets, holiday meals and restaurants.

Chinese meals follow the usual three-meal pattern. Breakfast is quick—steamed buns, congee, noodles, or rice rolls, often taken on the go. Lunch is practical and quite modest: rice or noodles with a few cooked dishes or a one-bowl set. Lunch scales up in variety for work gatherings or occasions. Dinner is the main social meal: several shared hot dishes plus a staple carbohydrate, sometimes with soup and fruit to finish. Weeknight family tables often feature 2–4 dishes and soup, served over a pot of rice.

THE AUTHENTIC CHINESE CUISINE

Authentic Chinese cuisine is far more varied and refined than stereotypes suggest. Many outsiders assume it’s greasy, salty, loaded with soy sauce and MSG. In reality, Chinese dishes use oil, but the stir-frying is quick, nothing compared to deep-frying. No oil-requiring methods of steaming, boiling, or braising are just as common.

Soy sauce isn’t universal; it’s one of many condiments, used differently by region: lighter and subtler in the south, barely present in parts of the north or west. MSG, often blamed for “Chinese restaurant syndrome,” is used sparingly or not at all in home cooking. Its role is filled by natural umami from mushrooms, seaweed, and fermented beans.

Many Western favorites, like fortune cookies, chop suey (stir-fry), or sweet-and-sour chicken, are inventions by Chinese immigrants to suit foreign tastes, not dishes found in China.

GRAINS IN CHINESE CUISINE

Grains are the base around which almost every meal is built. China is a dual-staple civilization, divided between rice in the humid south and wheat and millet in the drier north, a split rooted in river basins and a monsoon climate.

In the south, rice dominates. There are three main categories: long grain rice, which stays separate and fluffy when cooked; slightly shorter and softer medium grain rice; and glutinous, also called sticky rice. Despite the name, it contains no gluten; its starch makeup makes it sticky when cooked.

Rice extends far beyond the plain steamed grains that soak up stir-fries and saucy braises. Simmered into congee, it becomes a savory porridge; shaped and cut, it transforms into slippery noodles and silky sheets. When fermented, rice creates the base for cakes and puffed snacks. Rice flour forms pastries, the foundation for steamed cakes, and the translucent skins that wrap dumplings.

In the north, wheat staples dominate, but it isn’t baked into crusty bread. Instead, wheat foods are designed for stovetop and steam cooking rather than ovens: steamed buns, dumplings, noodles. These foods are hearty, matching a colder climate.

That is the oldest direct piece of evidence for noodles anywhere. China developed the full craft of hand-pulled (lamian), knife-cut (dao xiao mian), and hand-torn (mian pian) noodles. The noodle concept spread across Asia to Japan (ramen), Korea (guksu), and Southeast Asia, then globally.

Treating grains with alkaline or ash solutions is a distinctive feature. It involves soaking rice or wheat flour in alkaline water, made from ash, lime, or lye, to change the pH, texture, color, and flavor. Adding alkaline water strengthens the gluten and gives noodles a firmer, springier bite and a light yellow tint. Famous examples are Cantonese wonton noodles, lamian, and Hong Kong egg noodles.

Chinese cuisine often takes different starches – wheat, mung beans, peas, potatoes, or sweet potatoes – and instead of simply using them as flour, transforms them into new textures. They are recombined to make glass noodles, liangfen (a cool, jelly-like dish), and chewy wheat sheets for stir-fries and cold salads. The goal here is to explore texture as a creative space and aim for smooth, slippery, bouncy, or elastic sensations. This focus on mouthfeel sets Chinese starch cookery apart from the Western idea of pasta.

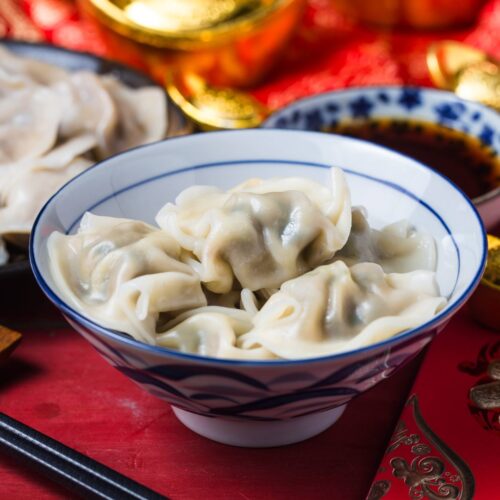

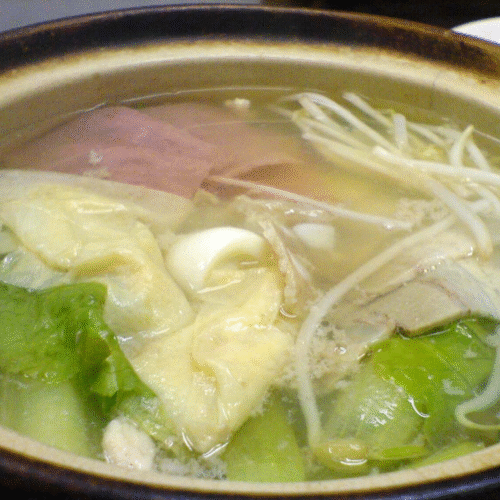

Dumplings are originally Chinese. The earliest dumplings date back over 1,800 years. According to legend, a physician Zhang Zhongjing wrapped minced meat, herbs, and spices in thin dough skins to feed and warm villagers suffering from frostbitten ears. The dish was called (jiāo ěr, tender ears), which evolved into jiǎozi over time. There are no official statistics to determine who consumes the most dumplings, but China could be the most likely answer. There are so many different types:

- Northern China: shuǐjiǎo (classic boiled dumplings with meat and vegetables), guōtiē (potstickers, first fried on one side, then steamed to give a crispy bottom and soft top), or zhēngjiǎo (thin skin, steamed dumplings in bamboo baskets).

- Southern China: delicate Cantonese har gow (translucent shrimp dumplings, a dim sum staple) and siu mai (open-top dumplings with pork and shrimp) in dim sum.

- Western China: thicker-skinned, spicier versions, often with lamb or beef, like suantang shuijiao (dumplings served in hot-sour garlic broth).

From China, dumplings spread across Asia – to Japan (gyoza), Korea (mandu), Nepal (momo), and beyond.

In Chinese cuisine, grains are also transformed into fermented seasonings. Black Shanxi vinegar is a dark, aged umami rich vinegar made from sorghum, barley, or rice. Used for dipping dumplings or adding depth to braises. Also a Huangjiu (yellow rice wine) – a fermented grain wine made from rice or millet that is both a drink and a cooking ingredient. Added for sweetness and aroma to drunken chicken or red-braised meats.

PRODUCE IN CHINESE CUISINE

Chinese cooking makes vegetables the star of the dish. Menus feature colorful veggie stir-fries, cold salads; many everyday dishes are built around greens. Fast, hot cooking is applied to veggies. Stir-frying over high heat quickly keeps true color and crunchiness. Quick blanching or steaming keeps greens bright and juicy.

Cutting matters. Mostly, depending on how long veggies need to cook: thin slices of ginger and scallion flavor the oil quickly, diagonal-cut stems stay crunchy, and crosswise cut lotus root keeps its snap. The cutting technique controls the final texture. Cooks are wisely using different parts of one vegetable, like leafy tops and crunchy stems, pods and roots, that adds variety without extra ingredients.

Aromatics are often treated like vegetables: leeks, scallions, garlic chives, and Chinese celery add structure and flavor and are used excessively, not just as a background fragrance. Bitter melon, chrysanthemum greens, and celery-leaf celtuce reflect comfort with gentle bitterness, balanced by garlic, ginger, and chili; never masked with cream or cheese. Clear soups highlight the sweetness of napa cabbage, winter melon or watercress; hot pot features mushrooms, greens, and tubers.

Soy is a big separate pillar in Chinese cuisine. As a cradle of soy cultivation, the Chinese used soy earlier than anyone else. Soy products evolved for centuries of experimentation, spread and shaped East Asian flavors, but no other civilization has integrated soy so completely for so long. Soy is used fresh, dried, fermented, curdled. It serves multiple roles:

- Protein source (tofu, soy milk)

- Condiment base (soy sauce, bean pastes)

- Fermentation medium (for complex umami sauces)

In most other parts of the world, soy became significant only in the 20th century, mainly as an industrial product (soy oil, animal feed, or health food).

China was among the first to intentionally cultivate mushrooms. Shiitake is traced back over 800 years, followed by wood ear, enoki, oyster, straw mushrooms. Mushrooms are valued for their texture and umami-building. Dried mushrooms, especially shiitake, are essential pantry items. Soaking releases a dark, aromatic broth that enriches soups and braises. Texturally, mushrooms supply the chew and bounce valued so in Chinese cooking, often paired with tofu and greens.

Potatoes aren’t the first thing people associate with Chinese cuisine, but they’re actually quite common, especially in the north and western parts. But not in a creamy and hearty way we are used to. They’re cut precisely, cooked briefly, and seasoned like vegetables — light, tangy, crisp. Potatoes feature stir fries, soy-braised beef or pork stews, their starch are used to produce noodles.

MEAT IN CHINESE CUISINE

For most of Chinese history, meat was limited, precious, used strategically to flavor vegetable and grain meals. Even today, stir-fries often use small amounts of finely cut meat, cooked with generous amounts of vegetables or tofu.

Average meat consumption has risen markedly in recent decades, and this has influenced meals, but not abandoning “meat-as-flavoring” logic, many households have layered more meat into existing formats (larger portions, more meaty versions of classics, and more frequent meat dishes per meal). Vegetable-forward and grain-based structures remain intact every day.

Meat is valued as much for the flavor it imparts to others (broths, sauces, oil) as for its own taste.

Pork is the everyday default meat. Chicken is both a weekday staple and the base for clear, refined broths; duck carries festive prestige. Beef, lamb, and offal are important regionally.

Pigs were independently domesticated in several regions. China was one of the earliest and most important centers, so pigs carry cultural significance and symbolize prosperity and family. Pigs thrived in China’s traditional farming system because they could be fed on crop byproducts and household waste.

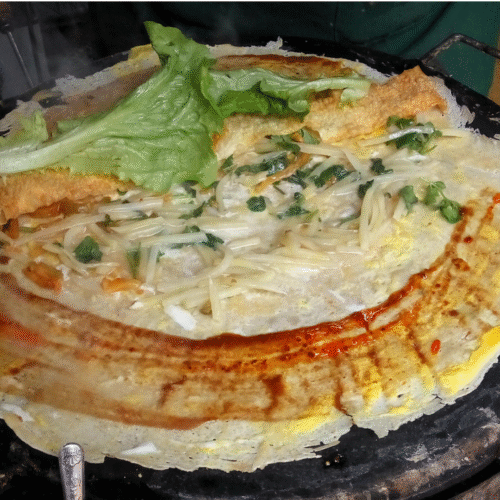

Cooking at the table, where diners cook their food during the meal, is associated with China through hot pot and tableside stir-frying/BBQ traditions, but it is not exclusively Chinese. In China, it’s clearest, lineage is hot pot (huoguo), which traces to Northern communal cauldrons and Mongol/steppe influences, when nomads together cooked mutton and its clear broth.Hot pot evolved into distinct regional styles and today is typically served with induction burners bubbling at the table’s center. Diners simmer raw thin cuts of meat, offal, mushrooms, tofu, and greens in shared broth. One pot may be divided into separate “yin-yang” parts, with mild and spicy broths. Additionally, there are dipping sauces (sesame, fermented bean pastes, chili oil, garlic) to personalize flavor. From China, the table cooking idea spread to Japan (sukiyaki and shabu-shabu (lighter, more structured versions of hot pot), Korea: jeongol and tabletop bulgogi grills, Vietnam and Thailand: lẩu and suki hot pots).

Stir-frying is the signature everyday cooking in homes and restaurants. The basic technique of cooking small pieces quickly began in Han era, when wood or charcoal was expensive, so quick cooking offered a way to save fuel. Later with time, iron woks became thinner and more responsive to heat than earlier bronze vessels. Improved stoves concentrated the flame on the wok’s base, reaching the high temperatures needed for wok hei—the smoky aroma unique to Chinese stir-fries. With Chinese immigrants, this stir fry spread, inspiring Japanese itame, Thai pad, and modern wok cooking everywhere.

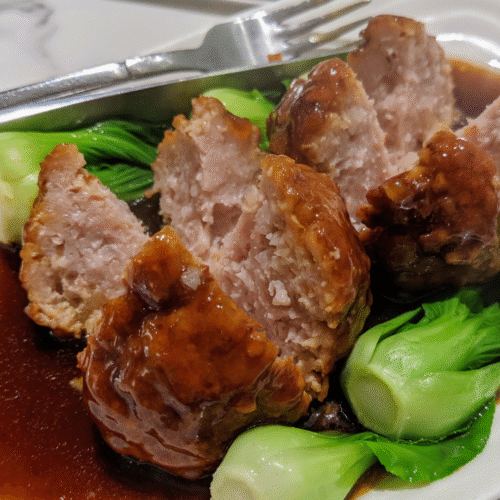

Several meat dishes are iconic in Chinese cuisine inside and outside the country. Peking duck, with crisp skin and sweet bean sauce from Beijing; Hong Shao Rou, a soy-braised pork belly from Hunan and Shanghai; Twice-cooked pork, a Sichuan favorite with chili bean paste; Dongpo pork, slow-braised and caramelized from Hangzhou; Kung Pao chicken, a spicy, nutty Sichuan stir-fry; and Char Siu, Cantonese barbecued pork glazed with honey and soy.

WILD TASTE IN CHINESE CUISINE

In Chinese food culture, you’ll find a variety of meats and animal parts that may seem unusual or exotic to many outsiders: duck tongues, duck feet, fish lips, scorpions, silkworms, snakes, and turtles. Also, very rare ingredients one would not imagine exist, such as dried fatty tissue near a frog’s reproductive organs, are used in sweet soups. These kinds of foods sometimes fall under the Chinese term Yewei, meaning “wild tastes”.

Guangdong, part of the Lingnan cultural region in southern China, has also been noted for its past consumption of cats and dogs; for instance, in Guangdong and Guangxi provinces, some older people traditionally consider cat meat a warming food during winter.

Many of the more exotic wild animal meats (terrestrial wild animals) are now formally banned for food use in China. That said, some foods that might seem exotic remain, particularly if they’re domesticated or farmed.

FISH AND SEAFOOD IN CHINESE CUISINE

Chinese cuisine utilizes nearly every edible species from the ocean. Turtle, shrimps, cuttlefish, squid, shark, abalone, and all kinds of shellfish. Fish is treated with respect, and so the Chinese don’t focus solely on filettes. Tail and bones are seldom removed. Fish are cooked whole, and most Chinese have no problem with eating the fish’s head. As fish has a very light flavor, other ingredients are added to give it what is considered “sufficient taste”. Fish steaming is dominant in the south, especially in Cantonese cooking; braising, deep-frying, or sweet-and-sour dishes are common elsewhere.

Favorites include steamed whole fish with ginger and soy sauce (Cantonese, clean and delicate), sweet and sour fish (tang cu yu, crisp-fried with a tangy glaze), squirrel-shaped mandarin fish (suzhou, admired for its artistry and sweet-sour balance), and spicy boiled fish (shui zhu yu, Sichuan-style, simmered in chili oil and peppercorn broth).

China eats mollusks in everyday home cooking, street food, hotpot, banquets, and restaurants; its total mollusk consumption is often cited at or near the top per capita. Chefs often cook seafood alive or freshly killed, using the same quick methods. Sauces are light—soy, ginger, scallion, Shaoxing wine, or a touch of vinegar.

Local favorites include steamed fish with ginger and soy, drunken shrimp marinated in rice wine, salt and pepper squid, crab with ginger and scallion, and abalone braised in oyster sauce.

EGGS AND DAIRY IN CHINESE CUISINE

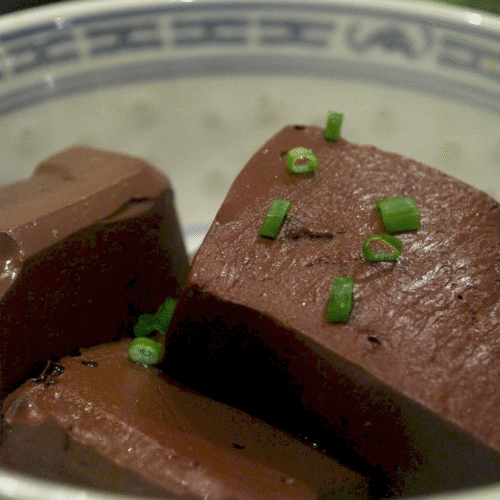

In Chinese culture, eggs represent birth and renewal – you’ll see red-dyed eggs at birthdays. Compared to Western cuisines, Chinese cooking uses eggs as both ingredient and highlight, in savory and sweet forms, fresh or preserved. Popular versions are steamed eggs, a smooth custard made with broth; tea eggs, hard-boiled and simmered in soy and spices for a marbled look; century eggs, preserved duck eggs with a creamy, earthy flavor; salted duck eggs, brined until the yolk becomes rich and oily, used in mooncakes or congee; and everyday favorites like egg drop soup and stir-fried eggs with tomato.

Milk and dairy are very limited. Most of the population was lactose intolerant, so milk appears just regionally: In Inner Mongolia and Tibet, people make yogurt, butter tea, and cheese-like curds. In Han Chinese cuisine, dairy mainly shows up in modern desserts, milk breads, and Hong Kong style milk tea.

Instead of dairy, Chinese cuisine relies on soy milk and tofu for creamy textures and protein.

OILS AND DESSERTS IN CHINESE CUISINE

Chinese cuisine favors plant-based oils and rendered animal fats. The most common are soybean oil for stir-frying, peanut oil, preferred in the south for its high smoke point and light nutty flavor, and sesame oil, used sparingly as a fragrant finish. Rapeseed (canola) oil is common in Sichuan and Hunan for high-heat cooking. Lard, that was once a staple, still adds depth to noodles. In some traditional broths and rice dishes, chicken or duck fat provides extra aroma.

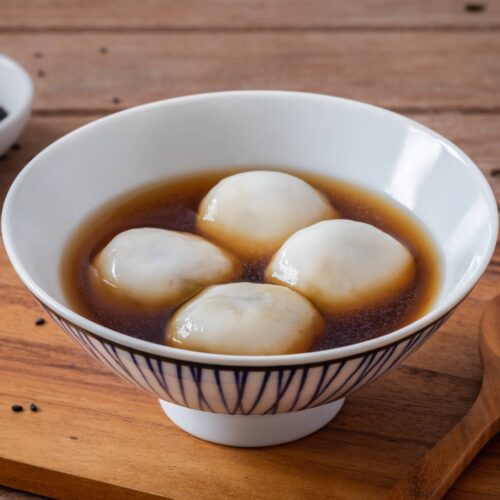

Chinese desserts are light, mildly sweet, and focused on texture. The usual dessert suspects are rice flour, beans, sesame, nuts, fruit, and mild syrups. Dairy and heavy creams are rare. Sweetness comes from red bean paste, lotus seeds, or glutinous rice, not refined sugar.

Popular examples include tangyuan, glutinous rice balls filled with sesame or peanut paste served in syrup or broth; mooncakes, dense pastries with lotus or red bean filling enjoyed during the Mid-Autumn Festival; almond jelly, a light, fragrant dessert often served chilled with fruit; sweet soups made from red bean, green bean, or black sesame, served warm or cold; and egg tarts, a Cantonese creation inspired by the Portuguese pastel de nata.