THE ESSENCE OF GEORGIAN CUISINE

Georgian table follows a principle of strategic abundance. Not excess for show, but insurance against want. You cook more than needed because hospitality demands it, because the neighbor might arrive, because scarcity lives in cultural memory. This is how people think about portions and variety. One dish isn’t enough; the table needs multiple textures, temperatures, and flavors available simultaneously.

Georgian cuisine balances meat and dairy with abundant herbs and sharp acidity. Fat and acid create the core tension. Rich elements (dairy, nuts, meat when present) always pair with sharp counterpoints: wine vinegar, pomegranate molasses, tkemali (sour plum sauce), pickles and this isn’t accidental. Heavy food in a cold climate needs something to cut through it, wake up the palate. Fermentation is also very common. Pickled vegetables, fermented breads, aged cheeses, wine made in buried clay vessels: they all deliver the enzymes and probiotics that modern nutritionists seek.

Wine is sacred. The 8,000-year-old qvevri evolved independently from Greek and Roman wines. Clay vessels buried underground maintain perfect temperature. Whole grape clusters ferment with stems, seeds, and skins, creating amber wines with structure and tannin that stand up to the food’s intensity. For non-alcoholic choices, mineral water, homemade lemonade, fruity compotes, tangy fermented drinks like kvass, and herbal teas are all popular. Coffee is a beloved ritual, paired with churchkhela, a sweet treat made with walnuts and grape skin.

A traditional Georgian feast, the Supra, deserves special mention. It celebrates family, friendship and community with tables groaning under impossible quantities of food: cheese, bread, pickles, walnut sauces, roasted meats, wine enough to drown in, everything arriving at once. Someone becomes tamada, the toastmaster, orchestrating the evening through toasts that follow ancient order: to peace, to parents, to the dead, to children, to love. Each toast demands a full glass emptied in one go. The food keeps coming even when plates are full. Hospitality here carries weight.

GRAINS IN GEORGIAN CUISINE

Wheat is the king of grains, providing flour for traditional breads tonis puri, shotis puri, lavashi, and khachapuri. Bread is both food and utensil, absorbing sauces and uniting disparate elements. Traditional bread is baked in a large, cylindrical oven called a tone. Shotis puri, a sub-type of tonis puri has a distinctive canoe shape and thickness, achieved by sticking long strands of dough to the inside of a round clay oven. Georgian lavash is unique compared to others (like the Armenian lavash); it is generally larger, sometimes up to 60 centimetres in diameter, and slightly thicker, with a pronounced puffiness in the centre, chewy texture and air pockets.

Khachapuri, a national dish and intangible Georgian cultural heritage, is an iconic family of savory pastries, served fresh and hot, stuffed with cheese and sometimes eggs, or meat. In 2019, Georgia introduced a “khachapuri index” to track inflation. It measures the cost of ingredients for one Imeretian khachapuri. This made a traditional dish an economic indicator. Regional khachapuri variations:

- Imeruli – The most popular form. Yeast dough filled with white Imeretian salted cheese.

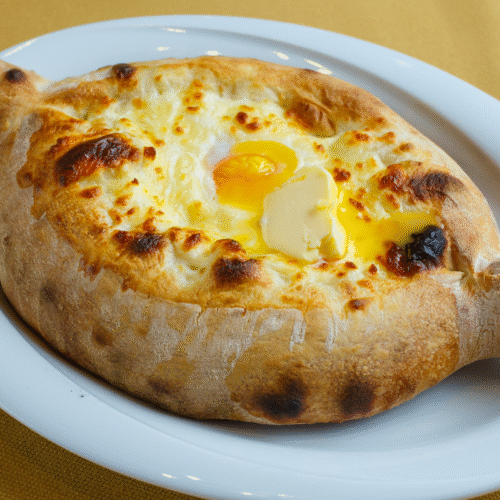

- Adjaruli – From Adjara on the Black Sea. Boat-shaped with cheese, butter, and an egg yolk in the center.

- Megruli – Like Imeruli but topped with extra cheese.

- Achma – From Abkhazia. Multiple layers resembling lasagna without sauce

- Guruli – Contains chopped boiled eggs inside. Shaped like a crescent calzone.

- Osuri – Ossetian style with potato and cheese filling.

Corn ranks second after wheat in popularity, especially in mountainous regions where it anchors simple, sustaining meals like ghomi (cornmeal mush), mchadi (cornbread), and chvishtari (cheesy cornbread). Barley has been cultivated for centuries, but plays a smaller role, appearing mainly as porridge in highland areas or as a thickener for soups. Rice arrived through trade routes and never became central, it shows up in just a few dishes: tolma (stuffed grape or cabbage leaves) and occasional pilafs like shila plavi or sweet versions with dried fruits and nuts.

PRODUCE IN GEORGIAN CUISINE

Any meat on a Georgian table is always accompanied by a large pile of vegetables and greens. No feast can do without a vast amount of veggie dishes. Greens are served all year round, but depending on the season, they can be parsley, fennel, ramson, mint, lettuce, basil, savory, estragon. Greens are often accompanied by garden radish, whole tomatoes, cucumbers, and peppers.

Georgian cuisine has a lot of vegetarian dishes made with beans, eggplants, and spinach. An interesting appetizer is pkhali, sometimes spelled mkhali – a cold pureed vegetables shaped into balls. Imagine a Georgian shepherd, high in the Caucasus Mountains, with a basket full of freshly picked greens and a pouch of walnuts. He roasts some nettles or spinach over a campfire, grinds them with fragrant herbs and walnuts, and voila! Pkhali is born. This might be a romanticized non-factual version, but it highlights the resourcefulness of Georgian cuisine.

Many families in rural areas practice subsistence farming: they grow their own vegetables and fruits, with little or no surplus for market sales. This portion of produce, coming from home gardens, can be underrepresented in official data sources.

People with knowledge and experience can harvest many edible mushroom varieties in Georgia; commercially available mushrooms in Georgia are less common. While not a staple ingredient in every dish, mushrooms are featured in mushroom chashushuli, a family-style stew featuring potatoes, mushrooms, onions, garlic, and herbs.

Fruits in Georgian cuisine cut through rich, heavy food. Plums become tkemali, a tart sauce that accompanies nearly everything. Pomegranates get pressed into molasses, which adds sweet-sour depth. Barberries, cornelian cherries, and unripe grapes all contribute acidity.

Georgia’s climate is hot and humid, and it produces intense fruiting seasons. People respond by making a creative product to preserve them – fruit leather tklapi, quite a unique ingredient. During fruit harvest, there is an abundance of produce that remains; tklapi offers a way to preserve plums, apricots, and mulberries for year-round consumption. To make it, fruit puree is spread thinly onto a thin sheet and sun-dried. Tklapi can be either sour or sweet, depending on the natural sugars from fruit: the sour version, made from cherry plums, is often used in soups and stews; served along with cheese, the sweet version from apricots or peaches features churchkhela dessert.

MEAT IN GEOGRIAN CUISINE

Georgian cooking omits no type of meat. There isn’t one single prestige meat, but high-quality pork neck, lamb, beef and chicken are valued, prepared simply with wine and herbs. Offal might not be on the menu at every restaurant, but it is beloved at home. Some mountainous areas hunt boars and rabbits.

Grilling over grapevine embers will surely happen during celebration regardless of the season. Mtsvadi chunks of marinated and grilled meat – any type, but the most popular is pork – on a skewer, is a celebratory staple, another national dish, one of the country’s oldest recipes. Key to mtsvadi’s success lies in the simple marinade, made from onions, garlic, herbs (tarragon or summer savory, for example), black pepper, salt, and acidic element: pomegranate juice, tkemali, or wine. Grilling happens outside, often in courtyards, vineyards, or nature, so it falls into the male sphere.

Chicken tabaka is a pan-fried poultry dish popular in other Caucasian cuisines. To fry thoroughly, the chicken is flattened out on a cast-iron pan and pressed by a weight. The chicken ends up golden brown and crispy on the outside while staying juicy inside, and is served with or traditional tkemali sauce.

Khinkali, also a signature food – succulent dumpling, made of twisted knobs of dough, stuffed with spiced meat. Initially, khinkalis were stuffed with lamb, the meat of the mountains. Later, variations of pork and beef appeared as the dish got popular and reached urban areas; then vegetarian versions were developed. Khinkali is eaten plain or with ground black pepper. The meat filling is uncooked when the dumpling is assembled, so meat juices are trapped inside. Warm water or broth is added to the chopped meat to make it even juicier. Khinkali is consumed first by sucking the juices while taking the first bite. The top is tough and is not supposed to be eaten, but discarded to the plate so that those eating can count how much they managed.

And finally, the stews. Thick, meaty, one-pot soups-stews are a staple in Georgian cuisine: kharcho, chakapuli, chanakhi, chikirtima, gupta, khashi, chakhokhbili – all provide comfort and warmth during chilly months.

FISH IN GEORGIAN CUISINE

The country’s agriculture favors livestock and crops more than sea treasure. Without well-developed fishing techniques and preservation, pre-modern Georgians might have struggled to catch and store enough fish to make it a staple. However, Georgia has a well-established freshwater fishing, particularly for bass species – largemouth and spotted bass – in its many lakes and reservoirs. Still, fish dishes make up a small part of traditional cuisine, particularly when compared with the abundance of meat recipes. Trout and carp are the most popular fish, usually fried or barbecued.

MILK AND DAIRY

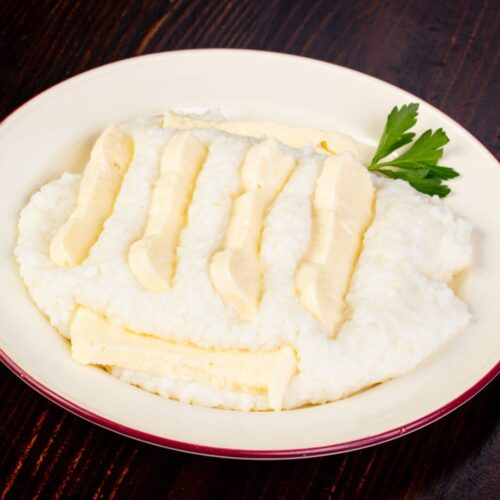

Georgians produce various old-recipe cheeses, like sulguni and imeruli. These are moderately salty cow’s milk products with an elastic texture. Sheep’s milk cheeses are also used for cheeses, like the pungent guda and smoked cheeses from the mountains. Though cheese is as integral to Georgian cuisine as it is in European cuisine, it plays a different role: it’s rarely served as a snack; Georgian cheese is very frequently added into hot dishes. It can be boiled in milk, roasted on a spit, fried in oil, baked in pastry, or flavoured with oil and spices to add depth. Besides the popular cheese-filled khachapuri bread, Georgians make several traditional dishes with cheese, such as nadughi, gebjalia.

Alongside cheese, matsoni/matzoon, a fermented yogurt, is a side to balance the richness. Matzoon is an Armenian product, distributed in Armenia and Georgia (source), sometimes called Caspian Sea yogurt. Matsoni has been patented in Georgia since 2012. For its nutritiousness, this yogurt is often given to kids and used in cakes, doughs, and marinades.

NUTS AND DESSERTS

Walnut trees have been growing in Georgia for millennia. They were once considered symbols of abundance and were planted near churches. To date, they are a Georgian staple, ground into pastes for sauces, incorporated into stews, or stuffed into meats to complement the meat flavours. Besides nuts, traditional recipes also call for walnut oil.

Walnuts blur the line between nut and fruit. They’re harvested green and pickled, creating an intensely flavored condiment. This early harvest tradition reflects a cuisine that thinks about plants across their entire lifecycle, not just at peak ripeness.

The most famous dessert also calls for nuts. Churchkhela – an overgrown pea pod-shaped dessert, made of nuts put on a string and repeatedly dipped in a mix of grape juice, flour, and honey. The most common churchkhela is made of walnuts, but hazelnuts, almonds are sometimes used. Churchkhela doesn´t have a striking taste, but since it’s light, durable, and nutritious, it’s worth taking a few pieces on mountain treks. And it´s also a very popular souvenir.

Georgian desserts have several distinctive combinations of characteristics: the use of nuts, grape juice or concentrated grape must, honey, fresh and dried fruits, flour, matsoni. Desserts are overall less sugary than in the West, and textural contrasts are important. One particularly distinctive aspect is that many are nutritionally dense and were traditionally used as travel food or energy sources during long journeys or physical work.